An absurdly named hacker, leaked financial and personal data, murky family money and a genocidal military are just four pieces of a story that sound like a Hollywood blockbuster.

Instead, it’s the reality of a trove of information leaked from post-coup Myanmar, 156GB of data released in early March. Since then, journalists and activists around the world have been scouring the information for clues about the sprawling investments of the Burmese military, also known as the Tatmadaw.

“To start off with, it was a bit overwhelming,” said one unnamed journalist from the investigative team of German broadcaster Deutsche Walle (DW). “My browser told me it would take 20 hours to download, so at that point, I had a brief moment of ‘What on earth am I going to do with all this data?’”

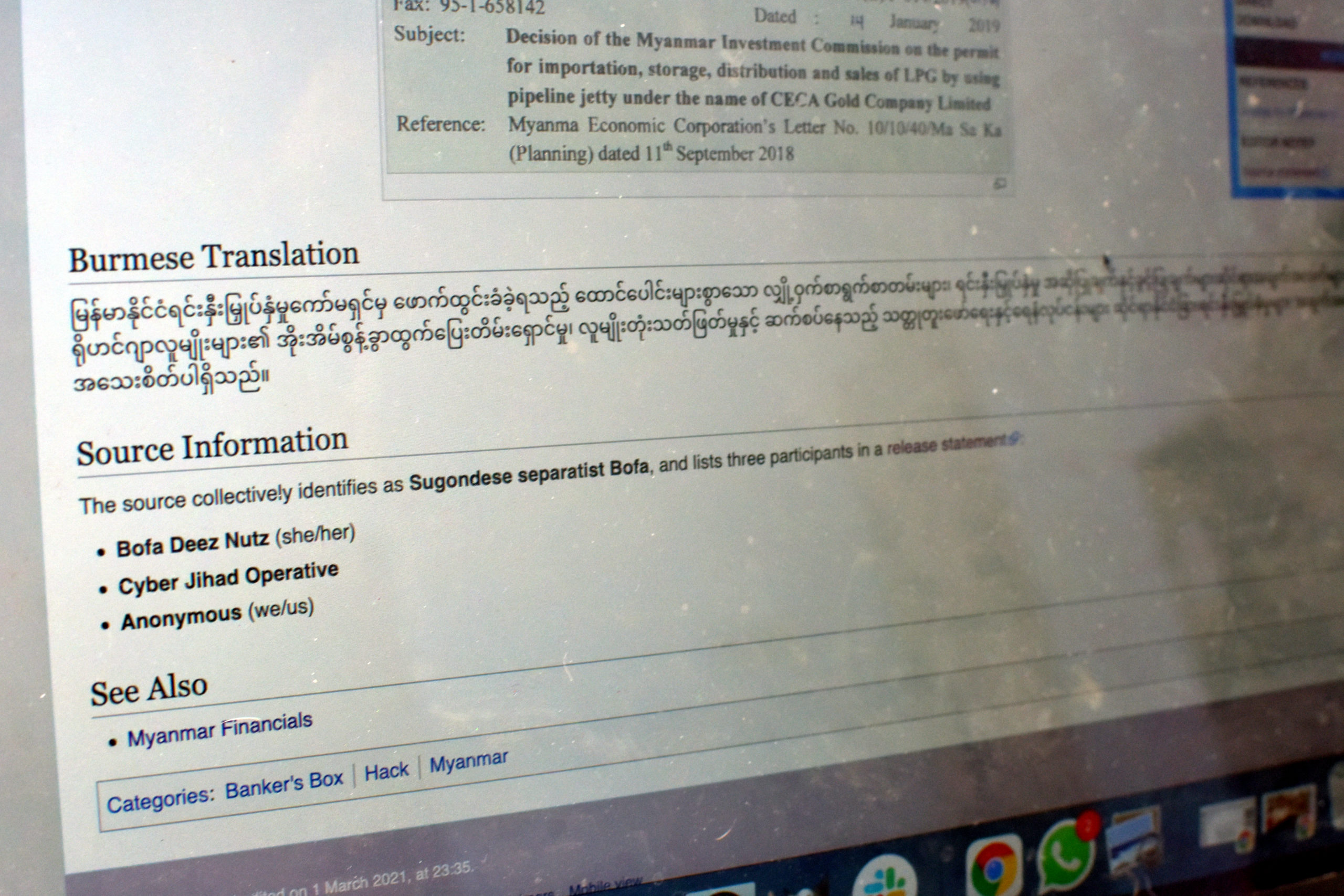

Overwhelming is one way to describe thousands of PDF files leaked and later posted on Wikileaks-style host Distributed Denial of Secrets (DDoS), especially when the job is figuring out how to use them effectively. In a hack by an activist working under the virtual nomme-de-guerre of Sugondese separatist Bofa (short for Bofa Deez Nutz), these documents detail proposals and projects from prospective and current investors in Myanmar.

Spurred by a cryptic promise left in the hacker’s postmortem report – which claimed the hack “directly relates to the finances behind the displacement and genocide of the Rohingya people”, specifically how foreign investment in mining and petroleum are linked to crimes against humanity – journalists and activist organisations leapt at the opportunity to make use of this data.

The Myanmar Investments hack is the follow-up to the Myanmar Financials scrape from months prior, popularised by activist expose organisation Justice for Myanmar, who has reported their findings on both.

But while this all sounds promising, to date, there’s no evidence as yet to prove this claim, and diminishing faith in the data’s ability to do so. For newsrooms equipped with the resources to sort through this trove, like DW, the realities and skills required to do it aren’t nearly as sexy as the nature of hacking makes it sound. After weeks of digging and deciphering through records of thousands of investments in the country, there’s little new information to go on.

In the world of data journalism, it’s not hard to find journalists excited by this leak.

Myanmar military attacks on the Rohingya, which saw an uptick in August 2017 that drove an additional 750,000 people from western Myanmar’s Rakhine state into refugee camps in Bangladesh, have long been understood as ethnically motivated. But if the hacker’s claims were proved true, this would mean that foreign investment and financial gain played a larger, and previously less understood, role in driving the violence.

But expert Chris Sidoti of the UN Fact Finding Mission in Myanmar – which began their work in June 2017, publishing their findings in September 2019 – said there was no evidence of this financial imperative from what he observed.

“At that stage, we didn’t see any land that had been cleared in the 2017 operation that had had a foreign investor occupying the land or making use of it,” Sidoti told the Globe.

The hack, sold as a key to uncovering the motivation for the genocide, has so far led DW reporters to uncover three previously unknown firms owned by the adult children of Tatmadaw Commander in Chief Min Aung Hlaing. Two of the general’s three children are already being sanctioned by the US Treasury, and it’s unclear what their newly discovered companies even do – much less what sanctioning them would do to dampen the grip of the coup regime.

An investigator who specialises in data journalism and asked to speak anonymously because of the nature of his work, says there are multiple complexities with data from the Financials and Investment hacks, both with the team and fact-checking required, and the technical realities of making it navigable.

“I’m not going to say leaks are not useful, leaks are definitely useful. But they can’t be the main source investigators rely on,” the investigator said.

“Any kind of information that helps the resistance come up with ways to look for who to boycott, who’s connected to who, is great. But it’s really hard for people to usefully use this data.”

It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack. It can also be quite frustrating when you don’t really get any direct results

DW’s reporter is no stranger to these complexities, nor is the wider posse that has joined the hunt. In a Signal group chat composed of half a dozen journalists, tech experts, and advocates, sparse conversation stems around tips on sorting through this mammoth trove and offers of fact-checking.

It’s common for teams like these to form, as it’s rare for one person to have all the skills necessary to make data usable.

“A lot of time was taken up actually indexing the data, figuring out how to use the database,” the DW reporter said about the process, which included technical support, translation, and fact-checking.

DW recently released their first report on April 9 after weeks of research on three additional companies which appear to be held by the children of Min Aung Hlaing. These companies are known as Pinnacle Asia Company Limited, Photo City Company Limited and Attractive Myanmar Company Limited.

Pinnacle Asia, led by the general’s daughter, Khin Thiri Thet Mon, seems to operate in telecommunications and possibly worked with the military-owned MyTel to build mobile network towers. But the leaked data has, so far, presented almost no information on the nature of the other two companies, which are listed under the names of Min Aung Hlaing’s sons.

Khin Thiri Thet Mon and her brother, Aung Pyae Sone, were officially sanctioned by the US Treasury on March 10. The siblings’ three previously unknown companies have not yet been targeted, but, given that it’s not clear what they do, it’s hard to say what value additional sanctions might bring.

Even finding these basic listings for the companies came at a great use of resources and hit many obstacles, including false positive matches to company identification numbers and joint ventures. Throughout the investigation, there were also questions of whether or not the data actually contains all company registrations.

“It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack,” said the Deutsche Welle reporter. “It can also be quite frustrating when you don’t really get any direct results.”

She says it’s too soon to tell if the data will make good on the hacker’s promises, but some other experts, like the data investigator, have expressed that the hacker might have made these claims without the assistance of translators or people on the ground.

“I don’t think they know anything about Myanmar,” the investigator said. “I feel like they just wanted to help.”

As these hacks become more prominent in Myanmar, a country with still-developing cybersecurity, he urges intentionality in examining the public good of the data prior to sharing it online. The data from the Myanmar Financials leak, which contained company registrations as well as an assortment of other information, like ID scans and passports, is now usable for journalists and NGOs, but he says there are privacy concerns.

“We’re talking about taking passport details of hundreds of thousands of people who just might have a bakery or something, and it’s now online, everyone can go look at it. I would say that’s slightly unethical,” he said, adding that Myanmar Investments doesn’t necessarily contain those specific privacy concerns.

It is not our role, as DDoSecrets, to anticipate all of how all data will be useful to the public, but we can provide an archive and a resource

DDoS believes by hosting this leaked information on their site, it will be of use to non-profit, academic, journalistic, artistic and anti-fascist groups.

“This lack of access to information is unjust. We believe it is useful to provide information that others would keep secret,” Lorax Horne, who’s part of the DDoS collective, told the Globe.

“It is not our role, as DDoSecrets, to anticipate all of how all data will be useful to the public, but we can provide an archive and a resource.”

Any push for reform, as well as the data required to do it, requires a “team sport” mentality, says the investigator. As activists, journalists, and hackers continue to uncover information in Myanmar, reliable data will need to come from other sources too.

“You can’t rely on leaks as a sustainable way to do investigations, because they’re going to be sporadic, they’re not going to have all the data that you would need,” he said.

“For that kind of sustained work, you need data that is more than just leaked.”