As a primary school student in Myanmar, Nay Myo Shwe saw green peafowls in the homes of his neighbours, with the birds often spreading their green-and-blue feathers in a dramatic display people referred to as ‘dancing.’

Even then it was clear the species “wasn’t a pet,” Shwe said. Now an ecologist who has studied the endangered bird’s decline as an adjunct professor at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, he points out the so-called dance is actually a mating call.

The domestication of peafowls is a big problem for conservation, even if people mean well, Shwe said.

“They love it, and misunderstand keeping it in the house,” he said, likening the habit to owning chickens.

The habitat of the peafowl, beloved in part because of its shimmering colours, is especially vulnerable. Typically found on forest edges near cultivated land, the birds venture out during crop season to eat grains that have fallen to the wayside and set up their nests on the ground.

Crop pesticides can be poisonous to the birds, while deforestation has logged trees that would otherwise provide protection from hungry dogs and curious humans. The birds only lay five to 10 eggs at a time, making each one precious, Shwe said.

Those perils have caused the peafowl’s population to dwindle in Myanmar and possibly reach extinction throughout nearly half its range in Thailand and Laos, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of threatened species.

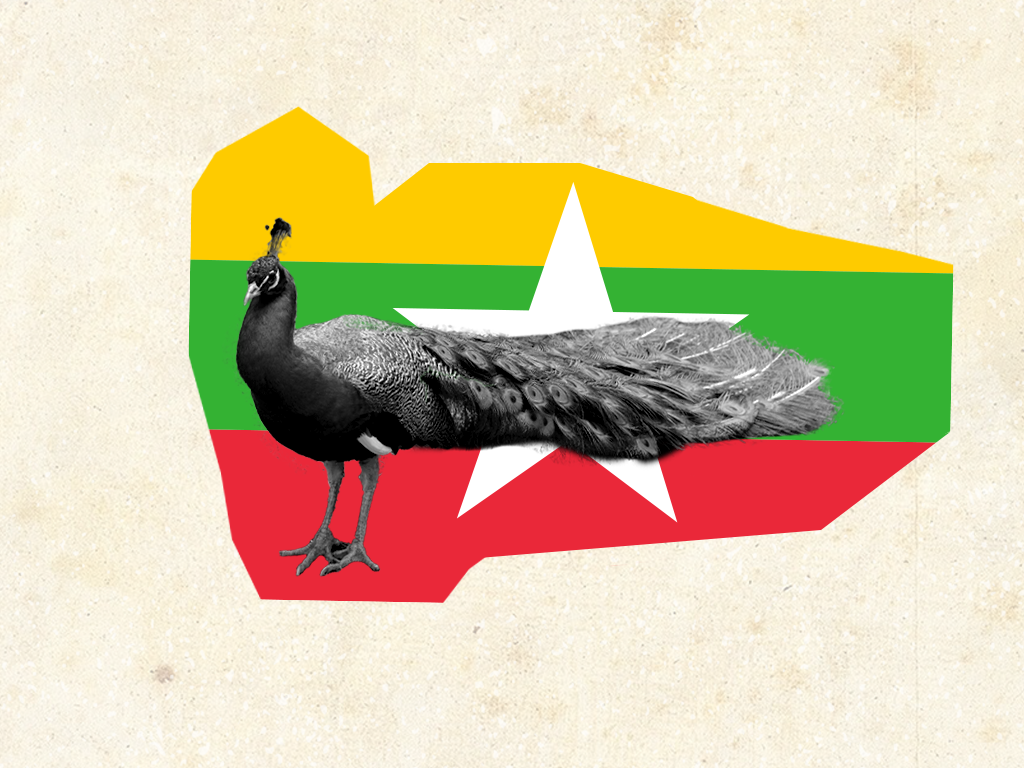

Yet the bird has a special connection to many in Myanmar, where the peafowl has been the national animal for at least the last decade, Shwe said, though no known legislation has made this official.

Aside from an unmistakable beauty, there is a well-known birth-story, or jātaka, of a past life of Buddha in which he was a peacock, said Paul Harrison, co-director of the Ho Centre for Buddhist Studies at Stanford University.

While there are differences to the peafowls’ colouring in certain stories, Harrison said the reception of the birth story is consistent across Buddhist cultures, which refer to him as the ‘bodhisattva’ in reference to his previous lives.

But knowledge of the peafowl’s link to Buddhism now varies greatly by region and generation, Shwe said.

“Culturally, people love this species,” he said. But, “if not properly protected, that species can be gone forever, soon.”

This article is part of Southeast Asia Globe’s World Wildlife Day Special series.