Crowded into the world’s largest refugee camps in Bangladesh, nearly 1 million displaced Rohingya witnessed Myanmar’s military coup on 1 February from the sidelines with a sense of familiar unease.

While the minority group were already facing dire circumstances, for those both at home and abroad, the recent putsch has made future prospects all the more demoralising. Though initially there were accounts of Rohingya in the refugee camps celebrating the arrest of National League for Democracy (NLD) leader Aung San Suu Kyi, the reality on the ground was a far more complicated mix of emotions, with one figure of oppression ousted by another.

As the military, known as the tatmadaw, faces condemnation from world leaders, there has been speculation as to whether General Min Aung Hlaing, chief of the armed forces and Myanmar’s de facto leader as of this month, could make overtures to the Rohingya to win favour within the country and among international partners. As of now, most Rohingya activists see little sincerity in these efforts.

“They raped Rohingya women and girls, burned down our properties, and killed many innocent people, even children. They did genocide on us. [They] cannot be forgiven,” Mohammed Tofail, a 24-year old Rohingya refugee living in Jamtoli camps in Bangladesh, told the Globe.

For those living in Myanmar’s urban centres, the last five years under the pseudo-democracy of the NLD, brought about a series of liberalising reforms. But for ethnic minorities like the Rohingya, the military has always been an ominous and ubiquitous presence, and many fear that their use of force will only increase following the coup.

For many Rohingya like Tofail, the Myanmar government is a monolith and all within it are guilty when it comes to the Rohingya genocide, regardless of their political party.

“Whether it was the power of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, or whether it was the power of Gen. Min Aung Hlaing – whoever is in power in Myanmar – we are always under persecution.”

When news broke on February 1 that the military had staged a coup, arresting Suu Kyi and removing the NLD from power, Rohingya in the Bangladesh camps were shaken at what it might mean for their future and their community back home.

“When I heard the news about the coup, I was shocked, but it has always been like this – even when we were back in our country before we fled,” said Mujibar Rahman, another 24-year old Rohingya refugee in the Jamtoli camps in Cox’s Bazar. “But, with the coup, I think it will be even worse because there will be [police] everywhere acting out against the community, acting out against the people.”

While violence has persisted throughout the decades against the Rohingya, the latest crackdown came in August 2017 when the Tatmadaw staged a series of ‘clearance operations’ against Rohingya communities, killing upwards of 10,000 and sending close to one million fleeing to Bangladesh. The violence was ultimately recognized as a genocide by the international community.

When we heard the news – first we wanted to stand in solidarity with all the people of Myanmar. We are not supporting anyone in particular, we just want to see all the people of Myanmar are having a peaceful life in a peaceful nation

Given their long history of military persecution, many Rohingya, like Tofail, felt an immediate kinship with those protesting in Myanmar and wanted to voice his support for the Civil Disobedience Movement, the campaign at the centre of the anti-military protests.

“When we heard the news – first we wanted to stand in solidarity with all the people of Myanmar,” said Mohammed Tofail. “We are not supporting anyone in particular, we just want to see all the people of Myanmar are having a peaceful life in a peaceful nation.”

Even though most Rohingya believe Suu Kyi has been complicit in the military’s genocide – pointing to her defence of the country at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in December 2019 – Tofail says all those in the camps in Bangladesh are nevertheless calling for her release.

“Here, in the camps no one is celebrating the arrest of Aung San Suu Kyi,” continued Mohammed Tofail. “However, I will not support her [personally] because when there was a case at the ICJ, on behalf of the military, she stood and covered up for all the things that the Myanmar military has done to us. So Aung San Suu Kyi is also involved in the genocide.”

Rohingya organisations, like the Rohingya Women’s Network, have similarly spoken out against the putsch, condemning the coup and calling for global resistance against military rule in Myanmar.

Once hopeful for repatriation back to their home country, years – and even decades for some – languishing in refugee camps has diminished any faith in the promises of politicians, both in Myanmar and internationally.

Talk of repatriation began shortly after the 2017 crackdowns with a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Myanmar and Bangladesh, giving international aid agencies, including the UNDP and UNHCR access to Rakhine state. Yet, each time the topic of repatriating Rohingya was subsequently broached, conditions for return were deemed either unfavorable or unsafe.

Covid-19 did little to help these efforts, with most countries, including Myanmar, firmly shutting its borders. Now, with the military back in full control, hopes of returning home, already rendered mere pipedreams, have now been almost entirely quashed.

Less than 24 hours after the coup, the military instituted a new cabinet, populated by openly anti-Rohingya ministers. The new Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, Dr. Thet Thet Khine, who, as per her title, will now be overseeing all resettlement efforts, has previously defended the military’s violence against the Rohingya, dismissing their role in the genocide.

Nay San Lwin is a Rohingya who fled Myanmar in 2001 and serves as the co-founder of the Free Rohingya Coalition, an organisation working to advance the rights of the persecuted ethnic group. He points to these past comments as indication that the possibility of full repatriation for the persecuted population is null.

“[Dr. Thet Thet Khine] is completely anti-Rohingya. If repatriation takes place, she has to deal with the Rohingya. [The military] has chosen people who are completely anti-Rohingya, so we are not expecting anything.”

In a speech aired on February 8, Min Aung Hlaing made mention of bringing “refugees from Bangladesh” back to Myanmar in an attempt to showcase the statesmanship of his new regime, notably refusing to refer to the Rohingya by name and carefully foregoing any mention of citizenship upon their return.

But these are words that the Rohingya have heard before. In their eyes, a military that has continuously denied their existence cannot be trusted, explained Rahman.

“[Min Aung Hlaing] was lying, not once – he has been lying so many times. At the beginning when we were crossing the border to Bangladesh, he said ‘there are no Rohingya in his country.’ He says that we are people from Bangladesh. This means that he is lying.”

We don’t see any possibility with demands for repatriation because this new military government is the same as the last government and we don’t see any hope from them

Zaw Ki, a 30-year-old Rohingya refugee in the Kutupalong camps who works with the Voice of Rohingya, a grassroots organisation offering a platform for Rohingya voices in Bangladesh, is similarly skeptical of the military’s promises.

“We don’t see any possibility with demands for repatriation because this new military government is the same as the last government and we don’t see any hope from them,” said Zaw Ki. “It’s all a kind of show, but we don’t expect any changes [with repatriation] right now.”

Even if the opportunity to repatriate became genuine for those in Bangladesh, the military’s conditions for return would require the Rohingya to give up their citizenship status by accepting ‘National Verification Cards’ – known among Rohingya as “genocide cards” given their disenfranchising effects. For many, this is unthinkable.

“We are waiting here in Bangladesh for there to be an agreement to give us back our citizenship rights, our freedom of movement, our safety, and our protection,” said Tofail. “If these conditions are not granted, we will not go back to Myanmar.”

In a similar demonstration of appeasement, in the days following the coup, several sources told the Globe that they had heard of military personnel visiting the capital of Rakhine state, Sittwe, and its surrounding areas to offer tokens to residents.

Yasmin Ullah, a Rohingya-Canadian activist who previously served as president of the Rohingya Human Rights Network, heard about these visits but doesn’t believe these efforts to be credible.

“There were conversations, and money, that [the military] gave to Rohingya leaders and people in Sittwe right after the coup,” said Ullah. “But this is all a façade that they are putting on. They are just trying to appease Rohingya into accepting second-class citizenship.”

The military gave Rohingya some money, $350 I think, and 500 eggs. They were also explaining why they had to take over power, and they said that they should not engage in anything opposing the regime

Nay San Lwin also spoke with fellow Rohingya in Rakhine state about what was exchanged and discussed during these meetings.

“[The military] gave [Rohingya] some money, $350 I think, and 500 eggs. They were also explaining why they had to take over power, and they said that the [Rohingya] should not engage in anything opposing the regime because the situation will be ok.”

Ullah explained that the Myanmar military has very clear, underlying motivations in making these kinds of superficial gestures.

“It looks like they were trying to seek approval of people at this moment where the coup is being sort of singled out and targeted as something that is undesirable for the country, or undemocratic, they’re almost looking for support in that manner,” said Ullah.

4G internet was also restored for a day in townships across Rakhine state, following the world’s longest Internet shutdown which began in June 2019, further suggesting that the military was looking to make peace with embattled communities in the region. However this suspension was fleeting, and a new internet blackout was soon reinstated, not only in Rakhine state but across the country.

“This was one day of showing off to the rest of the world, or at least to Rohingya in Myanmar, that [the military] was trying to change things,” explained Ullah. “They are trying to prove that they are better than the NLD, trying to legitimise their own stance.”

Both Ullah and Nay San Lwin note that the outreach visit to Rakhine had secondary intentions as well in making overtures to Rakhine Buddhists, the state’s majority ethnic group.

“[The military] is scared that the Rohingya will collaborate with the Rakhine, and this will be a serious threat for the military,” said Nay San Lwin. “They don’t want this peaceful coexistence because the Rakhine are always seeking independence, and if these two groups reconcile this could happen.”

While most Rohingya have fled Myanmar, and tens of thousands killed, at least 130,000 are living in internally displaced persons camps (IDPs) in northern Rakhine and southern Chin states where the circumstances are “unimaginable”, according to Nay San Lwin.

A small number of Rohingya also reside in urban centres, including Yangon, and see great responsibility in joining the resistance movement against the military given the hardships facing others in their community.

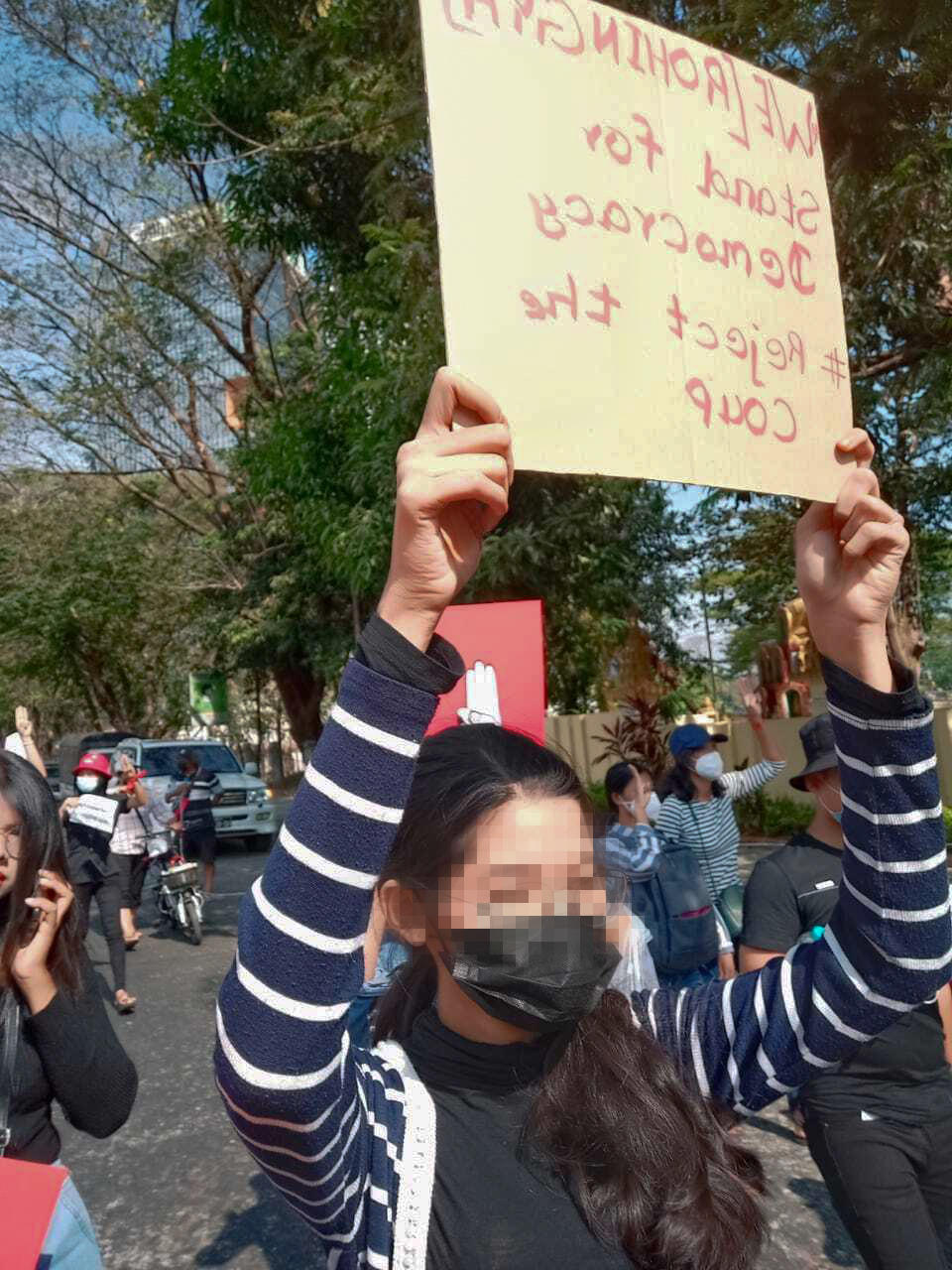

Samira, a 19-year old Rohingya activist, has been participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement in Yangon. Her real name has been concealed for her safety, but she believes that, as one of a small number of free Rohingya left in Myanmar, she has a duty to advocate for the rights and freedoms of her peers.

Samira lives in Yangon and has been able to move around freely by lying about her ethnicity on official documents, including her passport.

“[In the protest] I was the only one that took a card that said ‘Rohingya’,” said Samira, referring to the banner that she carried as she marched.“I felt a bit of fear but I have to be brave for my community. We have lost our human rights, our citizenship rights, and we have been deprived and suppressed, so we have a responsibility to fight.”

Samira, along with fellow Rohingya across the globe, including Ullah, are protesting to raise awareness about the disproportionate impact that the recent coup will have on the already-persecuted ethnic minority, but taking to the streets will only go so far, they also stress the need for international involvement.

Ullah notes that, in staging the coup, the military was likely emboldened by the lack of substantial international response towards the Rohingya genocide in the past.

“It is really important for [government officials] to see this coup for what it is. The military is going to try and put a spin on it, to try and smooth things out with the international community but there are a lot of people who will need help,” said Ullah.

“If the international community continues to do what it did for the past decade, it will slowly go down from here, it will not go up.”