In the early 1990s, Heather Lemonds and her younger sister were students at the Faith Academy boarding school on the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila.

A week before a planned visit back to their home country the US in 1991, her parents had bought the family tickets for the concert of American pop-star Debbie Gibson in Manila. The little girls were starry-eyed and thrilled. But in the days that followed, their excitement at the prospect of watching Gibson’s song hits Only in My Dreams and One Step Ahead quickly faded, shrouded in ash as the lines between day and night blurred under the mask of soot and phreatic steam.

The girls soon learned that Mt Pinatubo was erupting.

The volcano is located 90km north of Manila in west-central Luzon, with its name meaning “made to grow” in Tagalog. And indeed, Mt Pinatubo, which stood at a sweeping scale of 4,800 feet, started showing signs of stirring in April 1991 after more than 600 years of dormancy.

As he laid on the floor alongside his wife and infant daughter, on what felt like the longest nights of his life, English did not know if they were going to make it out alive

It was then two months later – on Philippines Independence Day, 12 June 1991 – that the first of several eruptions occurred. The days that followed paved the ashen paths to the most devastating eruption on 15 June, which would prove to be the second largest of the 20th century. So powerful was this eruption that the large volcanic ash cloud would drift around the world causing cooler-than-usual temperatures, impacting weather for several years after.

This year marks almost 30 years since those fateful events, but the memory of the moment remains vivid for those who lived through June 1991. The Globe spoke with the Lemonds, and several other survivors, about what unfolded in those darkest of days in the Philippines.

Beginning of the darkest days

A few days before the largest eruption, American Bill English was working at the now-closed US military base on Luzon, Naval Air Station Cubi Point, when loud explosions were heard overhead and the ground began to shake. He ran outside just in time to see massive plumes of ash being shot into the sky.

His troops were instructed to go home immediately. For English, his house was aboard the naval base itself, only a few minutes away. The others, trying to return to their families further afield, weren’t so lucky.

Another base closer to the volcano was the US military’s Clark Air Force Base, only 16 kilometres away. Clark was set to be struck hard, with Operation Fiery Vigil – the emergency evacuation of all of 15,000 US military personnel – called with immediate effect.

“All of them were evacuating at once,” English says, recalling how all the roads leading out from Clark Air Force Base were clogged with traffic from other vehicles frantically trying to get to Subic.

“Our families accepted these families into our homes, until they also were evacuated. All our food was shared,” he says. “That night became very dark, and all the power was out. At that time, we had absolutely no idea what was happening as no news could get through.”

English recounted how the following three days was pitch black outside and “not even a flash light could see through it”.

As he laid on the floor alongside his wife and infant daughter, on what felt like the longest nights of his life, English said he did not know if they were going to make it out alive.

Black Saturday

It was on June 14 that a less powerful eruption struck. Victor Davis, who was part of a rescue team, recounted that despite its comparatively small size to what was to come, it was one of the most horrifying sights he had seen.

“It looked like a nuclear explosion, the mushroom cloud kept growing larger and larger. And then the sun was blocked out. At 10am, it was pitch black dark; you couldn’t even see your hand in front of you.”

But the worst was yet to come.

The next day was the eruption’s apex, with an avalanche of magma and coarse fragments made even more potent by another element thrown into the mix, Typhoon Yunya, which happened to be simultaneously passing through. This deadly combination of extreme weather events culminated in a mix of torrential rain and ash clouds that descended heavily upon the Central Luzon region.

“There was no sun. It was inky black with volcanic ash, mixed with rain, accumulating at a rate of an inch an hour,” said Master Gunnery Sergeant Ted Szewcyzk, who was leading US marines in the Philippines at the time of eruption. “The darkness and ash fell for more than 22 hours, potent earthquakes shook buildings.”

Central Luzon was plunged into a darkness that lasted for 36 hours, with buildings either buried in mountains of ash, or collapsed under its heap.

Eventually, this final display of nature’s prowess resulted in such a substantial expulsion of rock and magma from beneath Mt Pinatubo that the volcano’s summit collapsed into itself, and as if the volcano had finally belched itself thin, it went back to slumber.

The aftermath

On June 17, the ash finally stopped falling. But by then, the damage had been done. Left in the wake of the volcano’s reveille after a six-century dormancy was a death toll of over 700 lives and the displacement of 200,000 people.

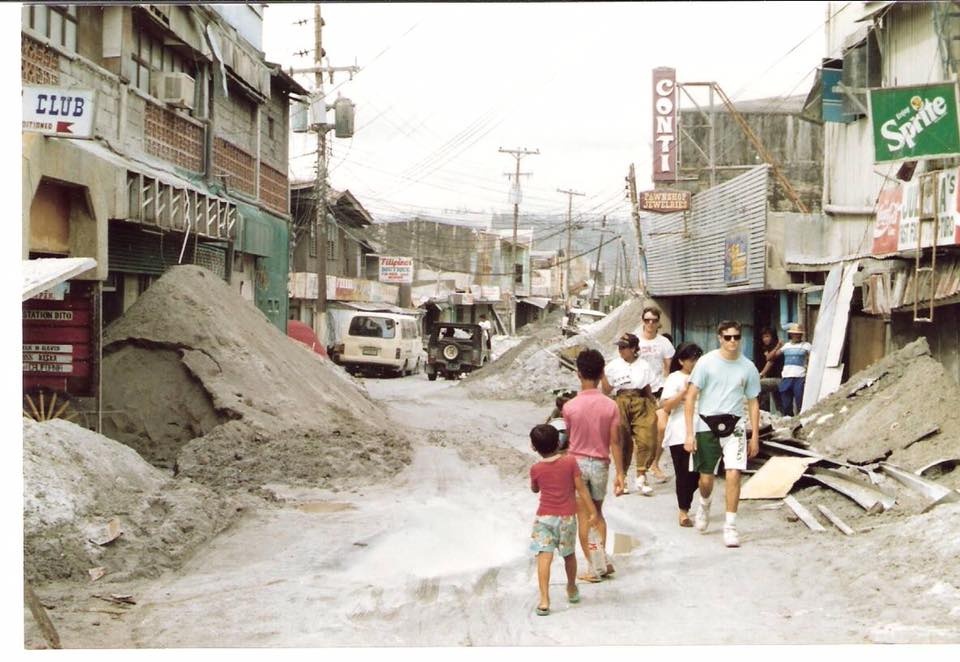

The Debbie Gibson concert never happened, and as Heather Lemonds flew to the States a week after the eruption, she remembered seeing “grey snow” all over Central Luzon. “I definitely remember walking in the dark rainy ash for days whenever we left the apartment – I’ll never forget that.”

Indeed, the landscape was drastically different, with everything buried in grey ash “about five to seven feet in depth” according to Davis.

“The jungle was levelled; most of all the trees had been broken like toothpicks, homes of the villagers had collapsed and despair was everywhere. I was in awe of the devastation. What was the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen was now a grey dust bowl; the smell of the tamarind tree was no more,” he added.

However, a few years later, when Davis revisited the area, he remarked how the local Filipino community “still smiled as if nothing had happened”.

“They’ve got a ‘life goes on’ type of attitude.”

Rising from the ashes

Bayanihan is a Filipino expression which means “being in a nation or community”, a nod to the unity and cooperation of its people.

In the past, in rural areas populated by nipa huts, Bayanihan was a concept used to refer to the act of helping a neighbour or family relocate by literally carrying the entire house from one place to another.

Bayanihan has taken many forms throughout the years, but in June 1991, with no houses left to carry, all hands went on deck helping each other build new homes and lives from scratch.

On 16 June, then-president Corazon C. Aquino declared a “state of public calamity“, before creating the Task Force Mt Pinatubo which coordinated all rehabilitation and resettlement efforts for the affected communities.

Filipino Paul Angelo Solinap, translating for his parents who helped in those recovery efforts, said that immediately in the eruption’s aftermath both civilian and military resources were mobilised.

“All the bridges around the volcano were decimated,” his father recalled. “Many towns, especially in the lowlands were buried in a mix of mud and ash.”

However, in spite of the destruction, casualties remained relatively low despite the scale of the disaster. Solinap said his parents recalled how some Filipino communities were either aware of the volcano’s abnormal behaviour beforehand, or alerted by forecasts in time. “Most of them relocated to safer distances or fled to other towns to take cover,” his father said.

English also recounted how “everyone was helping each other to get out of the mess” and that the US troops provided food to the locals, as well as formed teams that headed out into badly hit areas to deliver food daily.

In addition, while the Lemonds sisters were safe near Makati before their flight, their father had headed back to a badly hit site to offer help. “I remember hearing about homes being crushed by the weight of the ash and rain,” Lemonds recalled. “Many died or were homeless.”

Close to three decades since the Pinatubo disaster, many Facebook groups for survivors have been set up and are still active, with victims exchanging their experiences of a moment in history they shared, despite having since scattered to different corners of the world.

Many other natural disasters have unfurled in the Philippines in the three decades since, with among the most recent being an eruption that happened 145 kilometres south of Mt Pinatubo when Taal Volcano came alive in January this year.

“When it was happening, I heard commotion and people’s fears of how it could be a repeat of Pinatubo,” said Solinap.

While the death toll was much lower than Pintabuo’s at 39 casualties, the heavy blanket of ash that descended upon Batangas was reminiscent of that black mark in Luzon’s history. Harvests for the season such as pineapple, corn and coffee were compromised as 74,549,300 Philippine pesos ($1.5 million) worth of damage was incurred to local agriculture alone.

Paul Macalino was an hour away from Batangas, the province in which Mount Taal is located, when it erupted.

“We were all aware that Mount Taal was an active volcano. [But] the evacuation was a bit hectic as this was unexpected – nobody was ready,” he recalled. “Luckily though Taal lives in the middle of a lake. The lava that came with it dried out the lake. [But] plenty of wildlife was affected by this devastating eruption.”

Macalino said the Bayanihan spirit that excavated Central Luzon from the ashes three decades earlier shone through in Batangas, with assistance immediately deployed to assist the victims, some of whom were also survivors of Mt Pinatubo.

“Us Filipinos greatest trait is our hospitality. We are humanitarians who try to help each other. When the Taal eruption happened there were so many locals that would volunteer to help the ones who are affected by the devastating eruption,” said Macalino.

While life and politics has changed dramatically in the Philippines in the decades since Mount Pinatubo’s eruption, the scars of the events of June 1991 remain firmly etched into the psyche of those who lived through it.

With the country now battling a crisis anew in the form of the coronavirus, the Bayanihan spirit has once again been invoked through a new law passed by President Rodrigo Duterte in March (the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act) guiding communities through a different, but similarly unprecedented, kind of hardship.