Deep in the forests of northeast Cambodia, bamboo shoots criss-crossed rays of sunlight as 26-year-old Tang Kalann passed by open and covered pits near the Tang Se community, comprising four indigenous Jarai villages where he lives.

For years, the mining firm Angkor Resources Corp., formerly Angkor Gold Corp., had been surveying, digging and drilling all around Tang Se in hopes of building a full-scale mine in Ratanakiri province.

“This place has a lot of gold,” said Tang, hiking through white wildflowers and over fallen trees in the Andong Meas district near the Vietnam border. Near the top of the rise, Tang looked over the edge of an Angkor pit, now partially enclosed by mud.

Companies granted economic land concessions and, in the case of Angkor, mineral exploration licences have operated on indigenous land in Ratanakiri for decades under the protection of Cambodian law but without the consent of communities.

The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states applicants must gain Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) to use indigenous land. The standard calls for communities to be given complete information about commercial activities and an opportunity to approve or deny them without coercion.

“We knew absolutely nothing when the company started to come here”

Sal Ploeun, Tang Se community leader

While Cambodia voted in favour of UNDRIP, the country has yet to legally require FPIC. Most companies do not seek indigenous consent beyond conducting environmental impact assessments.

Angkor was no exception at first. Villagers spent years protesting the company, including prominently displaying a “no mine” sign and producing an opposition video with an NGO.

“We knew absolutely nothing when the company started to come here,” said Sal Ploeun, a Tang Se community leader.

The company and the community resolved the standoff in April through an agreement detailing Angkor’s commitments, which included securing collective land titles and guaranteeing rehabilitation of property used for mining. Both sides found the terms mutually beneficial and Angkor touts the accord as proving the possibility of an ethical agreement with an indigenous community.

Looking down into the pit, Tang said Angkor has become increasingly transparent since the agreement, but the negative experiences linger.

“They allowed people to come and watch, to see if there is an effect on the community land,” he said. “But I still don’t really trust them.”

Tang and other residents recall events in Peak Village, another Jarai community a couple hours away in Ratanakiri’s O’Yadaw district. The Indian mining company Mesco Gold made similar promises to invest in community development in exchange for mining rights in 2015. Mesco, which bought area land rights from Angkor, has since failed to deliver on many of its commitments.

The Angkor and Mesco agreements underscore the difficulty indigenous communities face in securing beneficial corporate relationships through negotiated agreements and their relative powerlessness to enforce implementation.

The area traditionally held by the Jarai community of Tang Se reflects a history shaped and remade by outside forces: the nearby border separating the village from its Jarai neighbors in Vietnam, ponds formed in craters left by bombs and ramshackle huts of the community’s old village left to be reclaimed by the jungle after dam construction increased flood vulnerability.

In the shade of a tree outside his home, where a string of green bananas ripened behind him, Kalann Dean reflects on the companies and officials involved in area projects.

“The reason we didn’t trust Angkor is that we had seen other communities which had bad experiences before,” said Dean, a community leader. “And we don’t trust the authorities because they value the companies more than the communities.”

Tang Se community members now conduct patrols to guard against encroachment.

Outside the residential area, a large rubber plantation meets a wall of wild grass, the border of property controlled by Vietnamese company 7 Makara Phary, which received a long-term government concession to farm there.

Red plastic ties later emerged on community land when Angkor established its working sites, leaving villagers confused and nervous about the company’s plans.

The man behind the red ties was Angkor’s silver-haired executive vice president of operations Mike Weeks, a former oil executive who has embraced Cambodian mining opportunities with his wife, Angkor CEO Delayne Weeks, despite a lack of industry experience.

Accompanied by his rescue dog Buddy on a December morning, the company co-founder showed off the Angkor’s headquarters in a former hotel in Ratanakiri’s capital, Banlung, where the company’s drill samples were stored. Across the street, Angkor had built an English learning centre, computer lab and dormitories for indigenous students. The company trained six indigenous women to produce thousands of sacks for the company’s ore samples, giving them a comfortable monthly income, Weeks said.

“We’re really on community development stuff,” Weeks said. “We work on economic development, not only in what we do, but in other industries for [indigenous people] as well.”

Listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, Angkor is recognised by the Canadian government for its corporate social responsibility programmes and FPIC standards.

A 2015 Oxfam report noted Angkor had one of the most clearly articulated FPIC commitments in the oil, gas and mining industry. But like each of the 21 firms analysed in the report, the company failed to fully employ the standard. Oxfam found Angkor prioritised development projects such as water tanks over empowering community decisions.

Tang Se villagers in Adong Meas district said they did not fully understand the company’s plans, the Oxfam report said. Looking back, village leaders recall they were unmoved by the good intentions professed by Weeks, in large part because they did not meet him for more than a decade.

Weeks said Angkor’s Khmer staff met with villagers over the years but advised him against interacting directly. The decision alienated community leaders who said they became frustrated by ignored meeting requests.

In late January Weeks met Gordon Paterson, a former NGO worker with strong Christian beliefs and close ties to the Tang Se community, where about one third of villagers are Christian. After Weeks agreed to work with the community and discussions progressed, Paterson drafted an agreement and the community eventually held a ceremony to “hand over” the land to Oeuy Dey (Creator). The agreement states Oeuy Dey, a term for God used by Jarai Christians that overlaps with traditional Jarai spiritual language, “placed the precious minerals in the ground to bless our Jarai communities as well as Angkor Corp.”

Weeks said the language was not his idea, but it did not hurt the agreement.

A community majority embraced the religious framing because “they have no other options left,” Paterson said, calling the agreement a “win-win” by improving relations from contentious to collaborative.

“The community know that they do not have the power to hold the company to their word,” Paterson said, “but since [Oeuy Dey] is integrally involved in this agreement, they have confidence that the company will follow or face consequences from the higher power.”

Indigenous activists are sceptical about incorporating religious language in a legal document, which shifts the foundation from community land rights to divine mandates.

“They [Angkor] use that term to make the community and their leaders feel that the land does not belong to them, the land belongs to God. It makes the community reduce their power,” said Saron Romas, a Highlander’s Association Jarai representative.

Tang Se villagers outlined their goals: better roads, improved access to education and healthcare, cultural preservation support and legal protection to guard against future government land concessions.

“The company gave us all the freedom to decide,” Dean said.

Besides commitments to help fund a costly collective land title, meet with a community committee and engage in economic development, Angkor agreed to include an important caveat concerning the future sale of the company or Tang Se land rights.

“If it’s sold, I can guarantee that whoever buys it from us has to sign off on this agreement and follow this agreement,” Weeks said. “And that was the final thing that allowed them to go forward.”

Nimol Van, a Khmer provincial programme coordinator for the Indigenous Community Support Organisation (ICSO), participated in the negotiations and said he was confident in Angkor’s ability to deliver: “What Mike says, he does.”

ICSO and Highlander’s Association, neither of which have lawyers on staff, reviewed the agreement before it was signed.

Highlander’s Association director Mong Vichet cautioned that imprecise language allows broad company interpretation. Indigenous Cambodian communities speak Khmer as a second language and may not be able to understand the details, he said.

Some of Angkor’s key promises are written in legally unenforceable language, according to Sophal Prum, head of human and land rights at ADHOC.

The company commits to help the Tang Se community sustainably manage the land and resources and “support and promote economic development,” which Prum said are good ideas but provide no specific guarantees or a timeline.

If there is a profitable mine the company promised an additional agreement, which “may include” renting the land at a fair price, working jointly on land use, compensating villagers for impacts and sharing an unspecified percentage of profits.

“What they [the company] mention is useless sometimes, because the company says ‘may,'” Prum said. “This word does not bind an obligation.”

Weeks said there was “nothing sinister” intended and he did not realise “may” precluded legal obligations, adding that the wording should be revised: “I’m more than willing to change that.”

Village benefits would be met regardless of mine development, Weeks said. Community leaders worried what would happen under a new mining company but said they were pleased with the current relationship.

“Nowadays it is like the company really understands us, because they will help us when we need them,” said Sal Oeun, a community committee member.

Angkor continues to survey, dig and drill to sample ore from thin holes reaching as far down as 135 metres (443 feet). The holes are eventually filled and owners receive compensation, but some remain dissatisfied.

Sitting beside a pile of freshly harvested rice, Kalann Puoch said she wishes the company never used her land because it disturbed farming activities and may eventually displace her without just compensation.

“If we didn’t have any company at all, I’d be happier,” she said. “I’m afraid of them.”

Angkor’s past engagement with the Jarai community of Peak Village in O’Yadaw province concerns the Tang Se villagers. Angkor began working in Peak in 2009 without permission or telling residents before the company collected samples. But the company also provided some social developments such as mango trees and water tanks, according to current and former village leaders.

Angkor sold its 12-square-kilometre (7-mile) exploration license in 2013 to Indian mining company Mesco, Weeks said. Village leaders claimed the community was not informed and lost faith in Angkor after the sale, while Weeks contended the sale was explained in a public meeting but accepted blame if villagers did not understand.

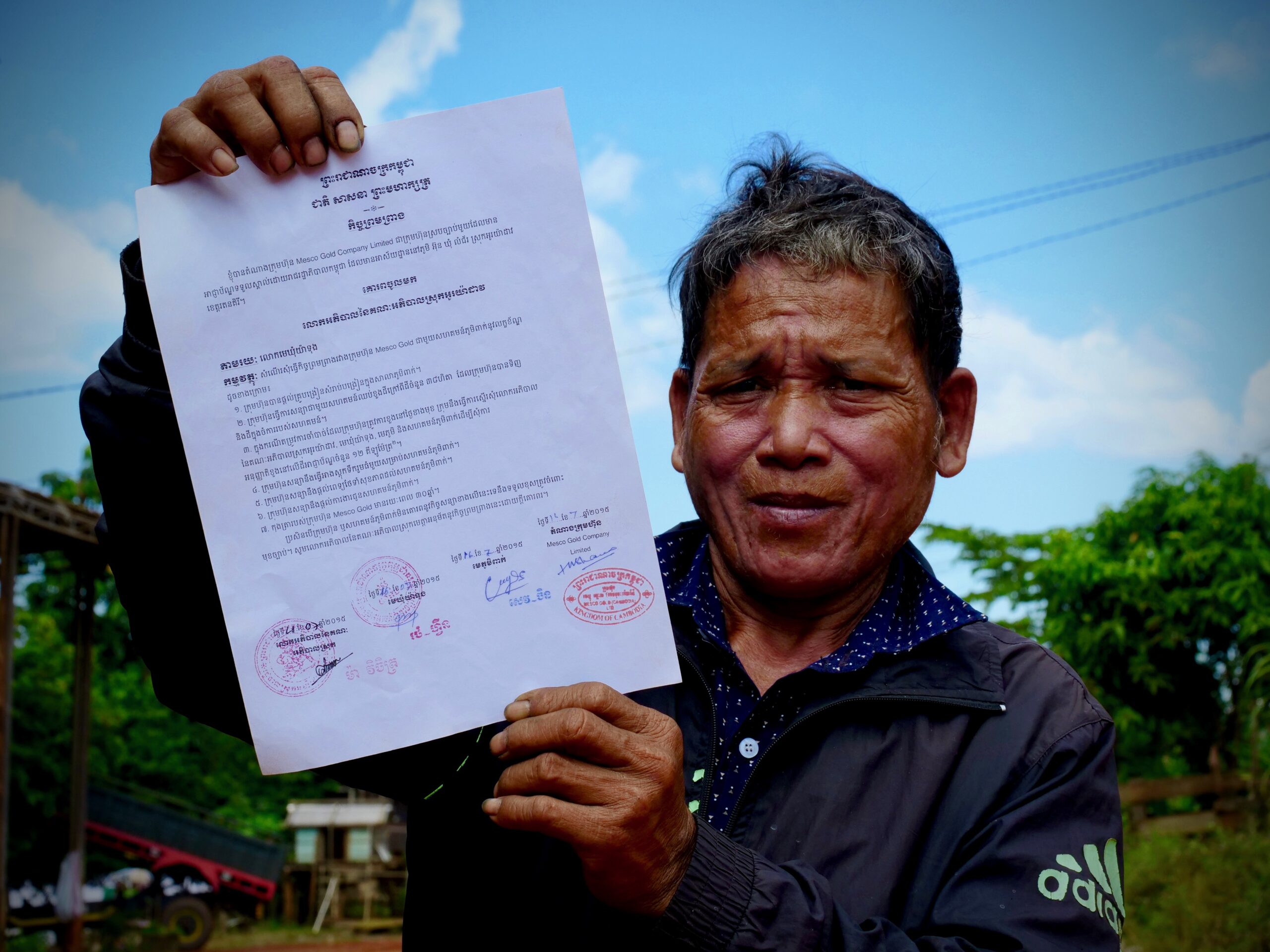

Mesco subsequently bought land from 18 community members. Villagers said they felt they had no choice since the company held government-issued land rights. Mesco and Peak village signed a one-page agreement in 2015 in which the company promised not to expand operations and to seek permission for additional digging.

Commune chief Rocham Fern said he authorised the agreement because the community wanted to prevent further expansion: “We were afraid. We sold this much land to the company but what if they want to spread and take more land?”

While Mesco upheld the commitment to stop expanding, villagers said other promised benefits were not delivered. Exasperated parents said a company-funded English teacher was regularly replaced, with each new teacher starting over with ABCs. A health centre was never built and a community drinking well was not finished.

Sev Byil said she wishes the community negotiated a rental agreement with Mesco. “We sold our land to them, now we cannot go into that land to find vegetables for food,” she said. “If we rented, maybe we can get money to provide for the next generation and the community.”

Southeast Asia Globe sent written questions to Mesco’s Cambodia manager Harsh Sharma and Vichea Un, the assistant to Mesco director Rajeev Moudgil.

Only Un responded, writing in a text message that “everything [is] going well with the compliance” regarding the agreement.

Mesco’s mining activities have halted since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, but the company’s mechanical manager, Chandan Kumar Pattar, said Mesco planned to restart operations soon. Community leaders said they were unaware of the intent to resume mining.

Mesco and Angkor are negotiating to develop further operations around Peak Village and Angkor has been drilling in the area again, Weeks confirmed.

Village chief assistant Sev Fin pointed to a large blue pipe jutting from cassava fields owned by his daughter, Sev Nang. The company drilled on the land without permission, with workers later claiming they were confused, Sev Fin said.

“I did not allow anyone to drill on my land,” Sev Nang said. “I felt upset, I was afraid that it would affect my land.”

Weeks said his company always seeks permission from landowners, but admitted there had been a mistake in the past year and the family’s complaint had been resolved: “If he still has a problem, he should come and see me because we’ll accommodate his issues.”

Weeks is optimistic about future operations in O’Yadaw district. He acknowledged the community was against him, but felt confident he eventually could secure consent for additional mining.

“If we get a deal with Mesco we’re going to work with the village and try to get a similar agreement like we have in Andong Meas,” Weeks said. “We’ll show them that we will do what we say we’ll do.”

Villagers said they are determined to resist Angkor’s plans.

“No, we don’t want them back,” said Runn, a farmer who echoed the sentiments of his neighbours. “Whatever Angkor offers again, the answer will be no.”

Additional reporting by Thy Rath and Sreynat Sarum.