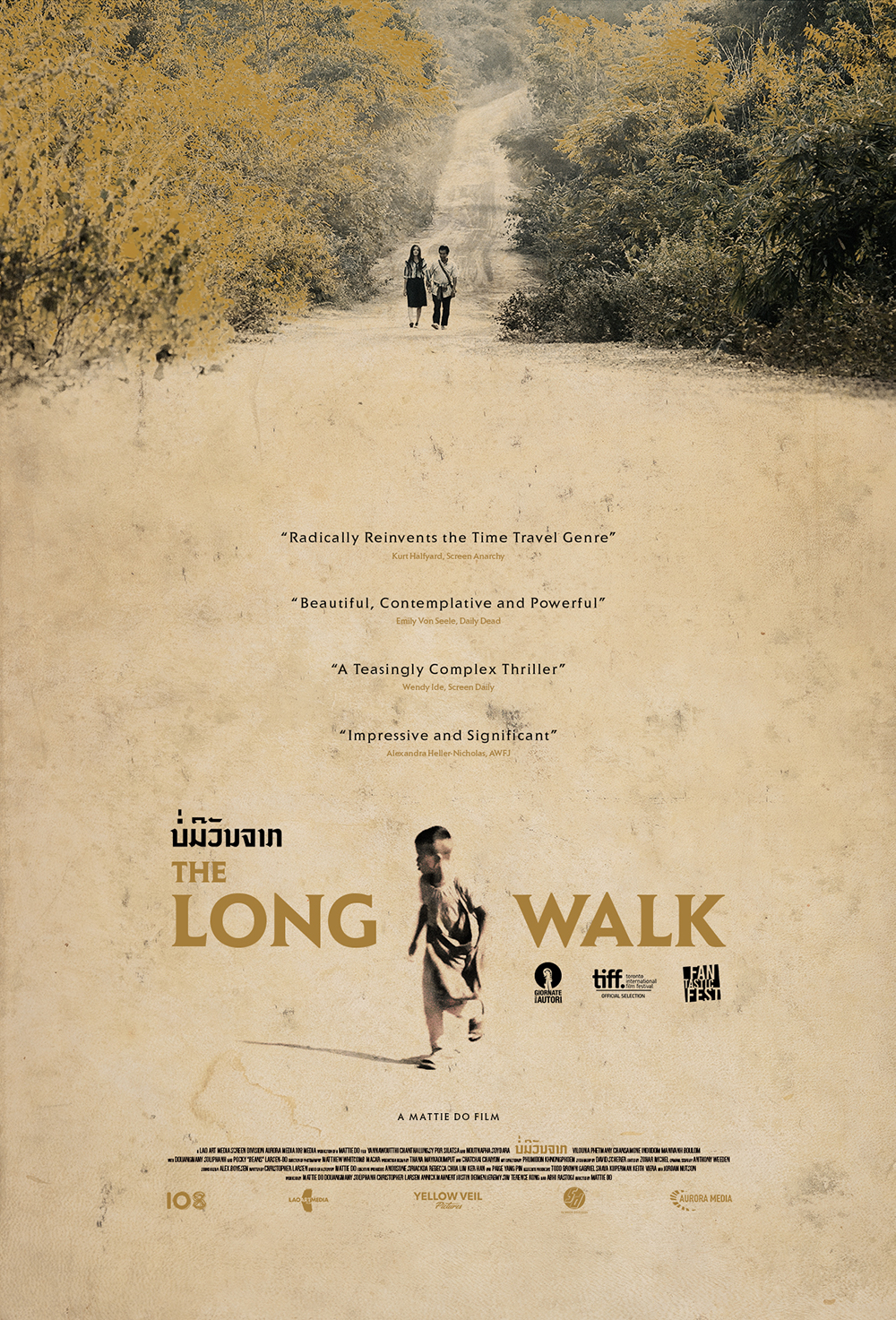

Ghosts, grief, regret, serial murder, time travel and colonialist critique. Mattie Do’s third film, The Long Walk, has it all.

The film is set in a dusty, rural village in Laos, a choice Do made to play into stereotypical visions of Southeast Asia and their depictions on screen.

Before The Long Walk, Do released Dearest Sister, which delved into class relations in the Lao capital city, Vientiane. The movie was called “offensive,” Do said, for not fitting the categorical expectation of Southeast Asian cinema: “Mystical poverty porn.”

“I don’t like that there has to be these boundaries and boxes,” Do said of the limited narratives viewers presume to be present in Lao films. “Everyone wants us to do these super artsy poverty porn showcases. Everyone expects us to have some kind of mystic oriental lotus blossom.”

One night Do and her husband, Christopher Larsen, who is also the screenwriter for her films, discussed setting a film among rural villages, dirt roads and huts – the hackneyed image of Laos – but subverting preconceptions with genre.

“Let’s give them their idea of ‘real Laos’ but with time travel and ghosts and a serial killer,” she recalled of the discussion.

The movie’s lead character, a time-jumping, bone-collecting murderer, puffs moodily from a vape, walks quietly along sunbaked roads accompanied by a ghost, buys bowls of noodles with a chip inserted in his forearm and decides when life is no longer worth living for the sick women he kills.

The film, released digitally on 1 March, is subtle and personal along with its barbed critiques of colonial mindsets, time travel and gore.

While writing the script, Do had to put down her beloved dog, Mango. The heartbreak of her pet’s death brought back the loss of her mother and morphed the work from a pure satire on “Occidental expectations” to “a study on grief and regret,” Do said. The Long Walk is dedicated to her mother and the whippet.

“The loss of my dog and how it brought back the memory of the loss of my mother when I was 25 just made it a really difficult year and it really worked its way into this film,” she said. “I always cry at the end of the film and I’ve seen it like a zillion times.”

Do was born in California to Lao refugees and grew up in Los Angeles. After the death of Do’s mother, her father retired to Laos and she soon followed with her husband and Mango.

Before becoming a director, Do worked as a makeup artist and ballet teacher. She started making movies in Laos. Chantaly, her 2012 debut, was barrier-breaking: the country’s first film directed by a woman, first to feature a female protagonist and first horror film.

Her new feature includes elements of the loss of Mango, the memory of her mother and the breadcrumbs of colonialism she has observed in the paternalistic manner that humanitarian aid is disbursed in Laos.

The lead character, shown as a young boy and as a middle-aged man, is poor in both iterations. We see him, played by 10-year-old Por Silatsa, washing dishes in a bucket and selling vegetables roadside with his mother, who develops a hacking cough.

In a darkly comedic scene, English-speaking aid workers visit the boy, his mother and father in their thatch-roofed home on stilts surrounded by countryside. The foreigners are accompanied by a Lao translator and the boy’s father excitedly explains the potential of the land for farming. “I really just need a tractor,” he says.

The foreigners walk briskly behind the home and pick a spot to install solar panels.

“Solar panels? But we don’t need electricity,” the boy’s father says to the translator. As they leave, one foreigner says to the translator: “Tell him I said you’re welcome.” The troupe exits the scene shaking the father’s hand and ruffling the boy’s hair.

“Sometimes you just have to have a little chuckle over just how wrongheaded certain things can be,” Do said of the scene. “There are times where there’s this attitude of superiority where these Westerners come in to save the savages… They come in and they’re like, ‘We know better what you need.’”

Do’s vision of progress, or lack thereof, is also represented in her take on futurism. The middle-aged version of the lead character, played by Lao actor and comedian Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy, lives in 2065 in the same home he grew up in and pushes around a dilapidated motorbike. Although villagers have tracking devices inserted in their arms, it’s not a glitzy interpretation of the future.

“A poor man in a rural village is still going to be a poor man in a rural village,” Do said.

Marketed as a horror film with time travel, there’s an unexpected realism to The Long Walk. Do shows the viewer what it’s like to watch the death of someone you love and the way relationships can continue and intensify with a loved one after death.

Do’s mother passed away before she turned 50. She was healthy and the matriarch of the family. In the third act of the film, Do recreates her mother’s death. She remembered the way her mother gripped the sheets, the way her family sat surrounding her, how her mother’s chest heaved and the sound of her last breaths.

It’s my gaze where I can lead the eye to the moments people may miss”

Mattie Do, director

As a 25-year-old watching her mother pass away, Do said she felt almost out of her body, observing the reactions of those grieving around her. Reimagining the moment on film allowed her to approach the experience again in a physical sense and include details she said are often missing from on-screen depictions of death.

“People talk about the male gaze and leading the eye to someone’s chest or someone’s butt… In this case, it’s my gaze where I can lead the eye to the moments people may miss,” she said. “There was a calming strength to being able to have that control.”

Do also wanted to impart the tangibility of spirits in Lao culture and in Southeast Asia more broadly. The ghosts in her film are companions, walking alongside the living, setting up picnics and taking trips to the market.

“I really love the way Lao people and Southeast Asians as a whole talk about the presence of ghosts like they’re people here with us, watching us,” Do said.

“For Lao people, the idea of spirits being ultra-tangible almost like a human standing next to you is very unique and I think people should see that.”