Ping. The notification bell goes off. A message slides in from Grindr, a dating app primarily for men seeking men. The message reads: “I think you shouldn’t have been born.”

Nickey Ross was 18 years old when he received the bitter text.

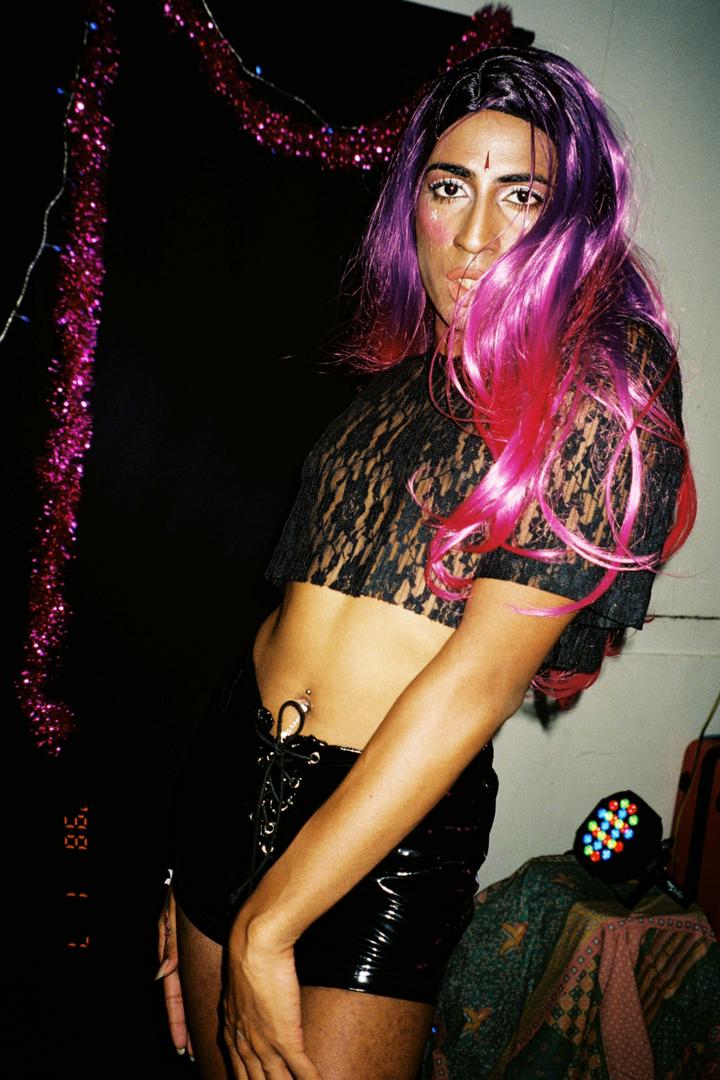

His drag persona, Miss BOOM, is a regular performer at Rainbow Rojak, a long-running queer party held at an undisclosed location deep in Kuala Lumpur. Frequently spotted in brightly coloured wigs, murderous high heels, crop tops and short shorts, both Nickey and his alter ego are no stranger to hostility, bullying and alienation for his presence.

Nickey started showing signs of gender dysphoria at the age of five. Eventually, he began to imagine himself as a girl, often becoming lost in traditionally feminine activities, watching The Powerpuff Girls and jamming out to Kylie Minogue through the night.

Growing up in a Malaysian-Indian household, Nickey’s parents weren’t always accepting of his non-binary gender expression.

“[My family] told me I can’t be feminine, but those were exactly my desires,” Nickey told the Globe.

Nickey now earns his keep as a drag performer, writer and tarot reader and bonds with his family over the television series RuPaul’s Drag Race.

He believes in hindsight that his parents were simply concerned about the potential hate crimes and societal discrimination their child might face.

But those early parental fears aren’t far from reality in Malaysia where, historically, transgender individuals were worshipped as ‘divine beings’ in Malaysian animist cultures.

However, the past several decades have seen a growing Islamisation of the country corresponding with a rising widespread narrative that being transgender is a disease to be cured, not an identity to be respected.

Now some transgender community members say death and rape threats and sexual assault are becoming regular occurences in the lives of Malaysian trans people.

After years of escalating state challenges to Malaysia’s LGBTQ community, some human rights groups are looking into legislation permitting a ‘third gender’ that would theoretically strengthen protections for transgender and non-binary people from discrimination. Such a move would enable changing identity markers on official key documents, possibly creating protections from state-sanctioned harassment or humiliation.

Such legislation might also eventually rule out one of Malaysia’s current go-to solutions for transgender people: the controversial practice of conversion therapy. Sometimes referred to as corrective therapy or reparative therapy, advocates of conversion therapy say their programmes can ‘cure’ queer sexual orientation or non-binary gender identities.

Around the world, conversion therapy is becoming increasingly taboo or even illegal, but in Malaysia the practice is alive and well, promoted by the state and private religious institutions.

The most popular among the conversion therapy paths is the Mukhayyam programme, a three-day camp held by the Department of Islamic Development (JAKIM) running eight times per year, mostly consisting of prayers and health and spiritual talks. In 2018, the programme’s organisers claimed about 1,450 people were successfully converted.

Though some programmes are more sparing, many efforts for conversion therapy are branded as similar to rehabilitation centres or marketed as loving communities, enticing participants with popular retreat destinations such the hills of the Cameron Highlands in Pahang state.

Stories of what goes on in Malaysian conversion therapies vary, with some of the most controversial involving the state-funded Islamic medical centres. Participants are allegedly sprayed in the eyes with chewed black pepper and then doused with vinegar water infused with salt and lime juice, all while overseers recite the Quran. According to practitioners, this is done to ‘wash the devil away’.

Other supposed cures are less physically damaging but can have harmful mental effects on participants.

“Every morning, they are asked to wake to pray, then they are asked to participate in masculine activities like playing games such as football, playing on the monkey bars and so on,” said Nisha Ayub, co-founder of two transgender rights NGO’s, SEED Foundation and Justice for Sisters.

“It’s not as extreme as being tortured physically,” Ayub said. “It’s more about using religion to correct your gender, expression and sexuality based on the binary religious system.”

In conservative Malaysia, anti-LGBTQ sentiments prevail in most non-English media outlets and religious institutions. A July 2020 statement made by then Religious Affairs Minister Zulkifli Mohamad Al-Bakri gave Islamic authorities “full license” to arrest transgender people and bring them “back to the right path”, a move decried by human rights advocates who said the government was leaving an already vulnerable community more susceptible to exploitation and discrimination.

While Islamic authorities target the transgender and LGBTQ community at large, rights groups are trying to reduce the stigma.

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) in June advertised a job listing for a researcher to look into the feasibility of legislating the recognition of a third gender, citing the likely discrimination, violence and humiliation faced by the marginalised group.

Even though no such proposal exists yet, SUHAKAM came under scrutiny from JAKIM, which demanded an explanation for the research proposition.

However, the path to better rights for the transgender community might not be as simple as legally recognising a third gender, according to Angela Kuga Thas of KRYSS Network, a non-profit organisation working on gender-based violence.

“Some transgender people do identify as male or female and they don’t want to be known as the third gender,” Thas told the Globe. “Using the third gender legislation to try to advance the human rights of transgender people, I fear may only reinforce the idea that the state has every right to deny or limit human rights because they happen to have the ‘wrong identity.’”

She fears without proper frameworks and policies, legislation would conform to the state narrative that only state-approved gender identities deserve legal protection and respect.

Members of the transgender community simply want to to be treated as regular citizens, Thas said.

Dr Joseph Goh, a senior lecturer in gender studies at Monash University Malaysia, explained that under the Malaysian Federal Constitution, all persons are equal before the law and entitled to its equal protection. Yet he said the reality is protection does not seem to encompass the transgender community.

Goh said this legal dilemma has religious overtones.

“Malaysians who do not conform to cisnormative and heteronormative rules are treated as sinful aberrations, which in turns justifies their exploitation, stigmatisation, discrimination and even death, until they are perceived as having successfully conformed to an existing category of gender as defined solely by anatomy.”

Nevertheless, both Thas and Goh believe the third-gender legislation could be a first step in the right direction, but only if deeper behavioural changes to protect transgender individuals are adopted in society and in the state.

For now it appears the direction of change is swinging away from greater acceptance of transgender or non-binary identity.

Ten days after SUHAKAM came under pressure, authorities tightened the sharia criminal laws while citing social media posts celebrating Pride month. The proposed amendments under the Syariah Criminal Procedure (Federal Territories) Act 1997 would allow action against social media users who post content perceived as insulting Islam by “promoting the LGBT lifestyle”.

Against this backdrop of conservative views on sex and gender, a 2019 study by SUHAKAM found 72% of the respondents had considered migrating abroad to access better protection and healthcare as a legally recognised gender.

Malaysians who do not conform to cisnormative and heteronormative rules are treated as sinful aberrations

During the Covid-19 pandemic, lockdowns mandated through the state’s movement control order have exacerbated the challenges of the transgender community to stay afloat while trying to keep out of the way.

Lacking the humanitarian aid that is easily accessible to others, some rely on community-driven fundraisers such as the Trans Solidarity Fund, an initiative by SEED Foundation and Justice for Sisters to provide everyday staples.

Nisha, whose organisations started the initiative, said the government’s Covid-19 financial relief schemes include benefits such as allowing citizens to withdraw emergency money from their compulsory retirement savings fund. While benefiting some people, Nisha says the effort excludes the large number of people in the community who make their living from informal employment sectors.

Although there is no official data, Nisha said at least 60% of the transgender community work in the sex industry, often due to limited career pathways.

“They don’t even have proper jobs. They don’t even have kids, so that makes it hard for them to apply [for other aid],” Nisha said of people outside the formal economy. “That’s why we started the fundraising. If you look at it, most of the time trans people have been left out of the bantuan (help) given by the government. So from there, you can visualise how difficult it is when an already marginalised group becomes more marginalised.”

In many cases, government outreach to LGBTQ communities does more harm than good, especially in the context of conversion therapy.

Condemned by the WHO and deemed illegal in Brazil, Ecuador, Germany and Malta, along with partial and regional bans in nine other countries, conversion therapy rooted in pseudoscience is also discredited by Malaysian freelance clinical psychologist Shaleen Chrisanne.

“You can use [conversion therapy] as much as you want, but research has shown over and over again that it does not work. It is a form of abuse,” Chrisanne said. “From a psychological point of view, we don’t make active choices in who we are as identities. [Gender identity and sexual orientation] aren’t something you can just choose or change.”

Goh agrees, emphasising that gender identity is a natural aspect of human diversity.

“[Conversion therapies] are false solutions to non-existent problems, they are evil in every form, they damage people and should never have been allowed in the first place,” he said.

Experts say discrimination and violence against transgender communities will continue to thrive in Malaysia as long as they are not granted respect or recognised, a hard truth of which the community members are well aware. Paired with crackdowns from religious authorities, Malaysia as a space for queer self-expression and societal acceptance is still something far out of reach.

“I know the reality, [legalising a third gender] cannot happen here,” Nisha said. “But if ever given that choice, I will be happy to be called just a woman.”

“[Religious authorities] always say we need to be ‘corrected’, that we need to be brought to the ‘right path’. I don’t know what path they are talking about.”