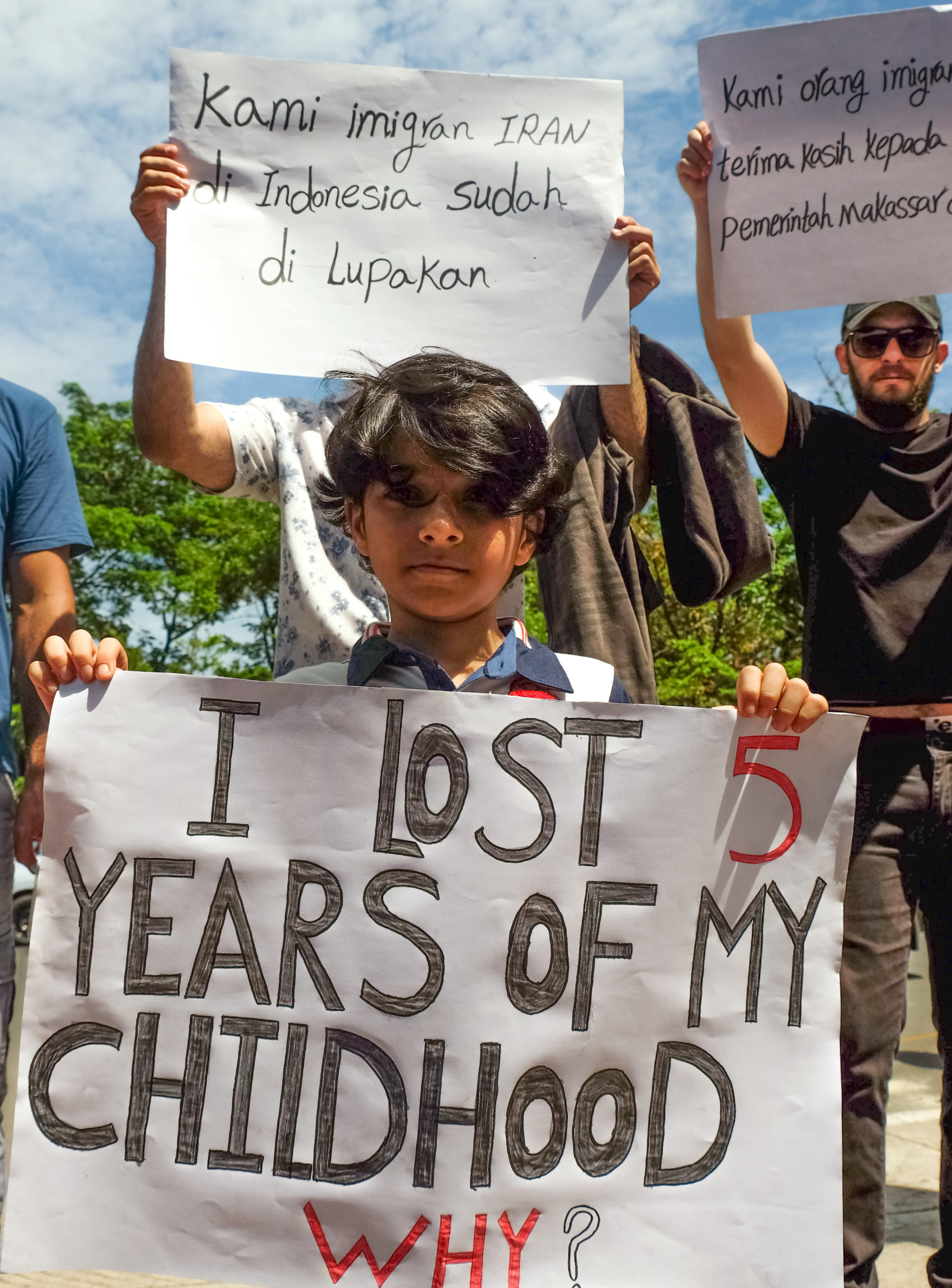

In Makassar, the fast-developing capital of Indonesia’s South Sulawesi province, refugees are protesting the rights-less limbo some have now been stranded in for a decade, with healthcare now high on the agenda as the pandemic grips the archipelago nation.

In mid-August, at least 40 Rohingya refugees, joined by local advocates, rallied at the legislative office in part to demand better access to medical care. True to the theme, most participants on 11 August were seriously sick, some in need of surgery, others suffering from infections or chronic illness. Their message was simple: To survive, they need either proper medication or resettlement to third-party countries where they can receive treatment.

“We want resettlement or local integration. If not, then we will ask for compensation over the years we have spent in limbo like refugees on Manus Island [in Papua New Guinea] and we will leave Indonesia ourselves to find safety somewhere,” read their demands.

For most protesting that day, their health prospects are bleak, and the proverbial clock is ticking.

“The hospital here told me that they have no treatment and that such surgery is expensive, which the IOM [International Organization for Migration] refused to pay,” said Muhammed Shiraj, a 44-year-old Rohingya refugee who has been suffering from gastric cancer since 2018.

He’s been stranded indefinitely for eight years in Indonesia, unable to move forward or back from his predicament.

“They recommended that I seek resettlement to a third-country where I can receive proper treatment. I have requested UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] several times for the resettlement, yet I have not seen anything. Nowadays, I vomit and urinate blood.”

Now, Shiraj says he’s asking for help from the Indonesian government because neither IOM or UNHCR are able to secure the treatment he needs.

Described by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as “one of, if not the, most discriminated people in the world”, the Rohingya are an unrecognised and persecuted ethnic minority group in Myanmar. Since 1982, they have been denied citizenship and faced rampant human rights abuses in their home country.

In recent decades, the Myanmar military has driven hundreds of thousands of Rohingya across the border from Rakhine state into Bangladesh. The most recent military operation, in August 2017, resulted in some 750,000 Rohingya fleeing into sprawling camps in coastal Cox’s Bazar.

In Indonesia, while life may not be as brutal as in Myanmar, the Rohingya, and the wider refugee community, experience acute hardship of their own.

Although given refugee status by UNHCR, the situation for the community in Indonesia remains heavily restricted. As a non-signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Indonesia denies individual refugees access to public health care services, as well as refusing them the right to work, travel and undertake formal education. They are not allowed to legally marry locals, and are discouraged from even maintaining romantic relationships with them. They aren’t issued a license to drive any vehicle, and for those living in IOM housing, refugees have a curfew from 10pm to 6am.

Refugees are left under the care of international organisations such as IOM, who themselves are dependent on Australian funding to operate. While some of these funds are geared towards humanitarian objectives like shelter, a monthly allowance and basic medical treatment, over 90% is focused on migration control measures designed to stop refugees reaching Australia. This lack of funds means that it remains a long, emotional and desperate process for refugees to get the medical attention needed.

Refugees under IOM have to go to a local public clinic, Puskisma, where they receive basic medicine for common illnesses at low cost. For refugees like Shiraj, medication is just not enough.

Since the massive global outbreak of Covid-19 the rate of sickness has increased considerably, because more than anytime refugees living in IOM shelters are stressed and isolated

Shiraj had a medical examination on 15 July at Wahidin Hospital in Makassar. The results were not good: He has now entered stage four cancer, with it spreading to other organs, especially his liver. In 2018, when he was between stage two and three, he needed surgery at Awal Bros Hospital, but he said IOM declined to pay for his treatment.

A couple of months later, when his condition had already worsened, he received an operation on his stomach. By then, it had been delayed too long, and the operation was unsuccessful. Some locals now help him with the costs of getting admitted to hospital, but his friends believe his condition is critical and are not sure how long he will live.

If refugees are seriously ill, Puskisma clinic provides a referral letter for the hospital, filled in by the patient. It’s slow moving, with letters collected once a week and the entire process taking up to two weeks or longer. Many applications for treatment are rejected. But perhaps the biggest flaw in the system is that many refugees in Makassar do not know how to read and write.

Faith-based organisation Church World Service assists with limited care in serious cases. Even still, cases pile up in a lengthy process of a month or more, with patients having to shout and plead their case to other refugee volunteers and case officers. Most simply give up and remain untreated.

The accepted cases then receive referrals to hospitals, sometimes after their condition has already worsened. During the pandemic, however, the medical system has now stopped all kinds of home visits to refugees nationwide, with focus now on handling Indonesia’s mounting Covid-19 patients as the country endures the most fatalities in Southeast Asia.

“Since the massive global outbreak of Covid-19 the rate of sickness has increased considerably, because more than anytime refugees living in IOM shelters are stressed and isolated,” said Erfan Dana, an Afghan refugee and community leader in Batam, the Indonesian islands closest to Singapore. “The IOM health care team in Indonesia is responsible for ensuring that no refugee’s sickness remains untreated and neglected.”

But for Rayas Alam, a Rohingya activist who has lived in IOM accommodation in Makassar for eight years, Covid-19 is just the latest addition to an already lethal cocktail.

“The coronavirus will not need to kill us, we are already dying here. Each year, one or two refugees die here,” he said.

In a written response to the Globe, IOM Indonesia stood by its efforts to accommodate all the medical needs of refugees and asylum seekers in Makassar.

“IOM’s medical panel carefully assesses cases and refers patients with acute or chronic medical conditions to qualified health specialists for short/long-term medical treatments whenever available in the country,” they said. “These assessments are based on referrals by local community health centers (Puskesmas) or their attending physicians, and costs are covered through IOM’s programme.”

They added that the organisation is ensuring that “displaced and vulnerable mobile populations, including refugees and asylum seekers, are not left behind and at risk to the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic”.

Many refugees in Makassar, living in overcrowded shelters with scarce resources and poor hygiene education, suffer from various diseases, including acute respiratory tract infections, cutaneous diphtheria, typhoid fever and malaria.

Jafar Allam is a 28-year-old Rohingya refugee suffering from kidney stones, a damaged urinary tract and complications from colorectal polyps.

“My life has been ruined in Indonesia,” Allam said. “I have requested help from the IOM several times, but they only gave basic medication when I needed surgery. They said it is expensive to pay for the treatment at a hospital. I am a man, but I am non-functional now.”

In March 2014, Allam was admitted to Labuang Baji General Hospital in the city. He suffered from kidney stones and had to have surgery. Several weeks post-op an infection began growing, culminating in a second operation on his urinary tract some months later. This operation damaged nerves, leaving him with impaired ureter functioning and excruciating pain when urinating.

Indonesia plays host to around 14,000 refugees, most of whom are minorities escaping conflict in countries such as Myanmar, Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, Iraq and Iran. A growing number have also, like Allam, been stranded in Indonesia for many years, becoming long-term dependents on organisations like IOM. Refugee resettlement in third countries, a dream for so many in Indonesia and elsewhere, is increasingly out of reach as the number of requests far outstrip slots for placements in countries that once opened their doors, most notably the US.

Most in Indonesia originally hoped to seek refuge in nearby Australia, but in 2013 the country shut its doors to refugees as it tightened efforts to stem arrivals to its shores through Operation Sovereign Borders. Matters were complicated further when Australia announced it would no longer resettle refugees in Indonesia who had registered with the UNHCR in Jakarta after 1 July, 2014, closing both legal and illegal asylum routes in the process.

In years past, refugees in the IOM system in Indonesia might wait a year or two for their next stage in life. Now, the organisation estimates about 60% of the refugees in its target population have been in the country for more than five years.

While no official Australian camps exist in Indonesia like those controversially created to detain refugees in Nauru and Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, the country itself has become a de facto camp of sorts. Refugees are subject to arrest and detention by local officials as Canberra has ramped up political pressure on Indonesia and IOM to prevent people boarding boats to Australian shores.

“We are affected by the same deterrence policies as refugees in Manus and Nauru [are], but we have been ignored by all kinds of NGOs and government agencies,” said Rubi Alam, a Rohingya refugee confined to IOM accommodation for the past eight years.

“Rohingya refugees in Makassar just want to find the best solution,” he added. “We are also human and want to be treated like normal humans.”

JN Joniad is a Rohingya refugee and journalist living in Makassar, Indonesia. He is an editor of the Archipelago writers collective.