Tax And Spend has rarely been part of the Southeast Asian governance lexicon. And judging by the region’s dismal tax-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios, it doesn’t look like that will be changing anytime soon.

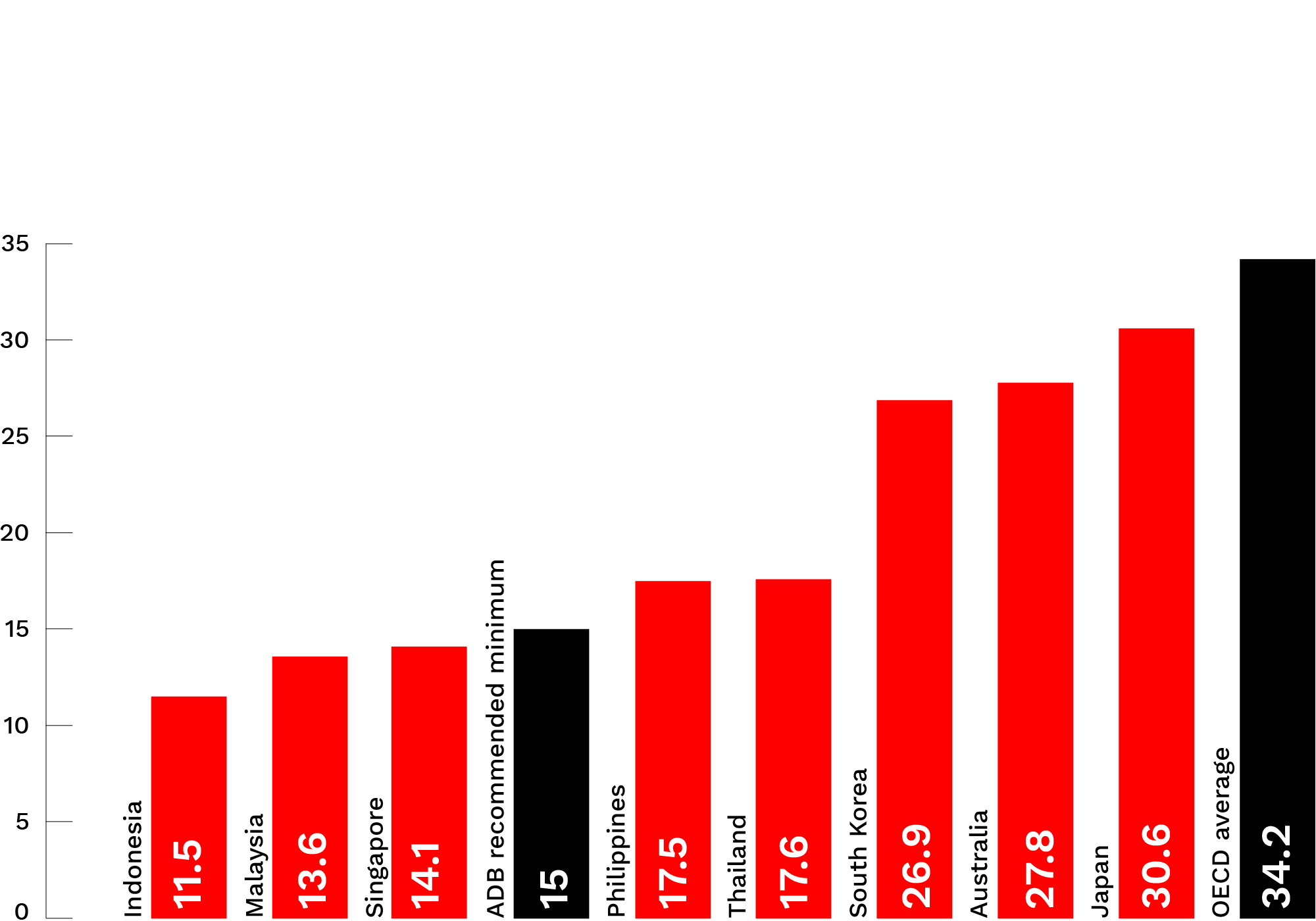

Newly published revenue statistics compiled by the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) show that the five biggest Southeast Asian economies have ratios of half or less than the 2017 OECD average of 34.2%, though most countries in the region showed small increases in revenues compared with the previous year. The OECD defines the tax-to-GDP ratio as “total tax revenue, including social security contributions, as a percentage of GDP”.

While more prosperous countries in Southeast Asia’s vicinity such as Australia, Japan and New Zealand all come in around the 30% mark, Southeast Asia’s own numbers were much lower, with Indonesia at 11.5%, Malaysia on 13.6 and Singapore only slightly above on 14.1. This last number in particular seems surprisingly low given that Singapore’s economy more resembles higher-tax Western counterparts than its neighbours in Southeast Asia.

“In Southeast Asia, as far as I know, inequality is increasing in Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam”

Christopher Choong, Malaysian development economist.

The best-ranked Southeast Asian countries were the Philippines and Thailand, both of which neared 18% and topped a benchmark mentioned by the Asian Development Bank, a Japanese-led regional lender based in Manila, in a July 2018 report. A 15% tax-to-GDP ratio, the ADB said, is “widely regarded as the minimum level required for sustainable development in the absence of other sources of government revenue.”

It’s not always easy. In Malaysia, the third-wealthiest country in the region per capita, a large agricultural sector cuts into the tax-to-GDP ratio. Farming, the OECD reported, is “a challenging sector to tax” as “most people [are] on low incomes and many are not registered for tax purposes”.

Tax-to-GDP ratio (%) 2017

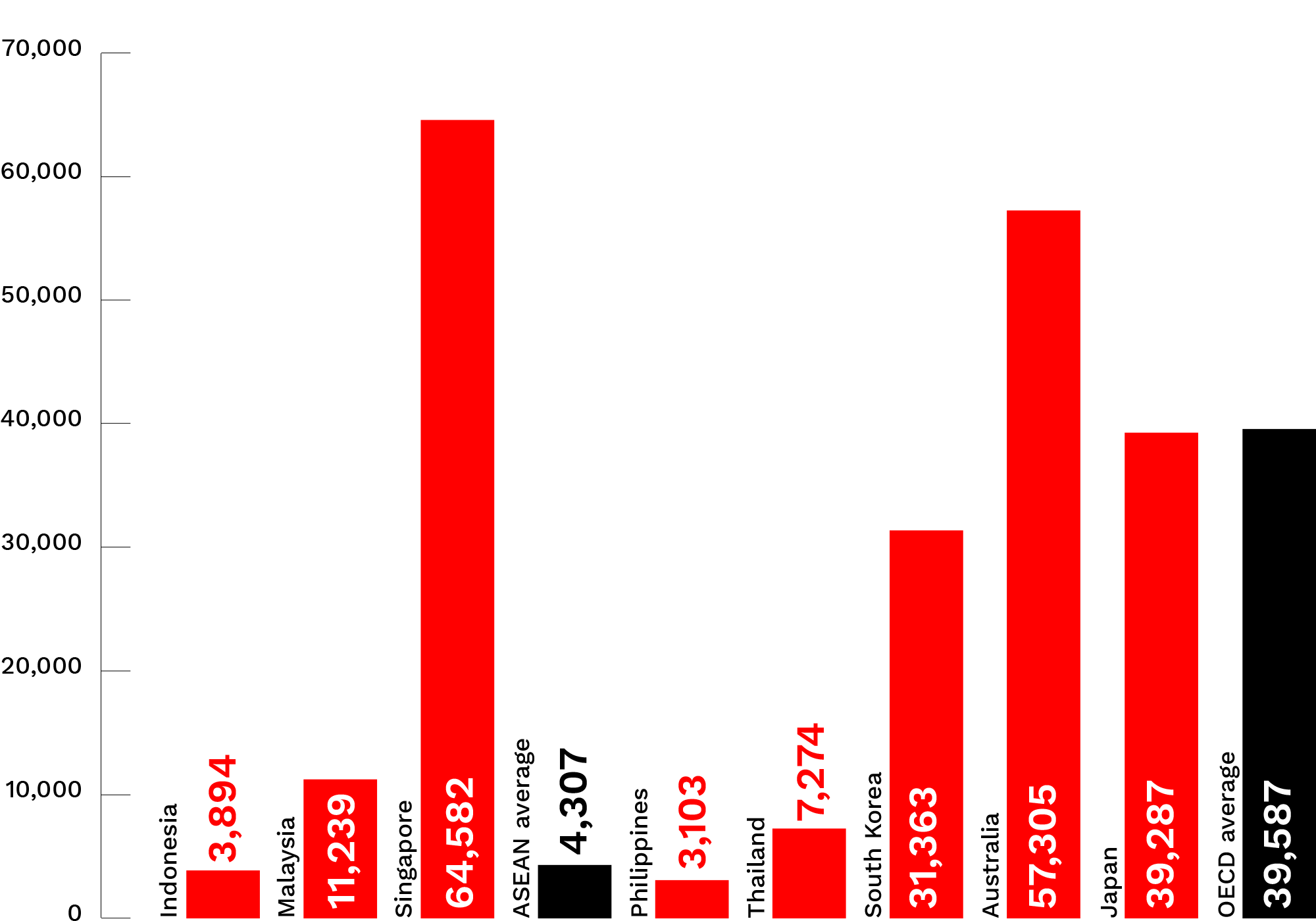

GDP per capita (US$)

The 15% target is arguably a fairer and more realistic benchmark than the OECD average for a region with a GDP per capita under US$5,000 – less than half the global average and well below high tax-to-GDP neighbours such as Australia, Japan and South Korea. That said, measurements published last year by the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) suggested that most Southeast Asian countries have tax-to-GDP ratios lower than what would be expected even when controlled for average per capita incomes.

For the more than 600 million people across Southeast Asia, these are more than just numbers on a spreadsheet. Increased tax revenues, if spent transparently and fairly, should in time lead to better and more widely available health and education systems, reducing overall inequality.

“In Southeast Asia, as far as I know, inequality is increasing in Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam,” said Christopher Choong, a Malaysian development economist.

“Government policies definitely have a role to play whether they are progressive fiscal policy, [such as] tax and transfer to redistribute income and wealth, or education and labour market policies to promote meaningful inclusion in the growth process, or social protection system to safeguard people from market fluctuations,” Choong said.

For now, there appears to be a trade-off: member-states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have much higher economic growth rates than wealthier, higher-tax neighbours in Asia. But the relatively senescent economies of Japan, Europe and North America have, over the decades since World War II, crafted complex and costly social spending systems and financed health, education and transport services that Southeast Asian countries hope to at least emulate.

In Asia, however, the tendency has been for “emerging” economies to compete to attract foreign direct investment. “To do so, generous tax incentives were provided for foreign investors,” the ADBI reported in a 2018 survey of the region’s tax policies.

In turn, high growth rates have not yet led to the sort of revenue yields needed to improve healthcare and schools or to build the roads and railways and ports required to facilitate continued economic development and higher living standards for the region’s 640 million people.

ASEAN statistics show most countries bar Malaysia and Vietnam spend less than the global average of 5% of GDP on education most years, with health spending percentages slightly higher, edging towards 7% in some cases but as low as 3% elsewhere. Most are well below the World Bank’s estimated global average of 10% for 2016.

British bank HSBC estimated in 2016 that Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam need over US$2 trillion in infrastructure investment through to 2030, while the following year the ADB came up with a figure of US$2.8 trillion for ASEAN as a whole.

With the region’s governments hard-pressed to come up with that kind of money, even countries that are wary of China’s growing global influence, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, nonetheless back Beijing’s mammoth intercontinental infrastructure blueprint known as the Belt and Road Initiative – “largely because they are desperate for infrastructure funding,” according to a recent report by Eurasia Group.

The Philippines is one of the countries seeking Chinese largesse, with President Rodrigo Duterte even downplaying alleged Chinese aggression in what the Philippines has long claimed as its territorial waters. The usually outspoken Duterte’s silence in this regard seems to be about keeping China onside and willing to live up to an array of recently made infrastructure building pledges and boost Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” slogan.

As a 7,500 island archipelago of over 100 million people, the Philippines needs to upgrade transport links if it is to sustain the 6-7% annual growth rates necessary to generate jobs for millions at home and entice back the ten million or so Filipinos who have emigrated to find work.

“As of 2019, the two main binding constraints on the Philippine economy’s continued growth remain its deficient infrastructure as well as major challenges in governance, corruption, and policy predictability,” said Jerome Patrick Cruz, economics lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University.

Duterte’s oft-criticised administration has broken with the previous government led by Benigno Aquino III in areas such as freedom of the press and human rights, but has continued his predecessor’s economic reforms, with the rising tax take – which doubled between 2010 and 2017 – praised by the ADB and OECD.

But what works in the Philippines might not work across a region made up of a diverse array of often highly unequal societies where millions of people live on the equivalent of a few dollars a day – and where ostentatious wealth often sits alongside poverty, sometimes literally, with glossy malls laden with designer goods towering over tin-roofed shacks and refuse-clogged waterways.

Increasing the government’s tax base “should in theory lead to relatively high social spending, in turn reducing overall economic inequality,” said Dr Lee Hwok-Aun, senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, a Southeast Asia-focused think-tank located on the grounds of the National University of Singapore.

But it is not necessarily so straightforward. Effective policy-making depends on a country’s economic conditions and levels of inequality, Lee explained.

“A country with low income, low inequality and low revenue intake might not need much revenue to redistribute and lower inequality, because inequality is low in the first place.”

“Indonesia has big tax potential represented by the total amount of the offshore assets declared during the tax amnesty programme”

Yustinus Prastowo, executive director of the Center of Indonesia Taxation Analysis

Although ASEAN has pledged closer economic co-operation among member-states, that is unlikely to include anything like an “ASEAN Taxation Way,” as any would-be common approach would be unlikely to work across the board in a region featuring divergent forms of government and vast differences in income levels.

While Indonesia and Malaysia are multi-party electoral democracies, Myanmar and Thailand are run by a combination of civil and military authorities, while Vietnam and Laos have been single-party states since the 1970’s. Malaysia and Thailand are so-called “middle income” countries with strong tourism and sophisticated manufacturing export sectors, while Cambodia and Myanmar are low-income, agrarian economies where urban jobs are in so-called “unskilled” sectors such as garments.

Governments face the dilemma of balancing the need for increased tax revenue against worries about losing business and foreign investment to lower-tax rivals or neighbours – further undermining the prospect of any common approach to solving the regions’ revenue conundrum.

Indonesia’s newly re-elected President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo conceded as much during recent campaigning – promising to cut corporate tax as an inducement to would-be foreign investors already wary of Indonesia’s protectionist-looking morass of red tape and relatively under-developed transport infrastructure.

That promise comes in the wake of a much-touted tax amnesty launched by Widodo’s Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati in 2016, when Indonesia’s wealthy were encouraged to declare assets stashed offshore and make themselves tax-compliant.

Before his first election win in 2014, Widodo said he wanted to increase Indonesia’s tax-to-GDP ratio to 16%, but the latest Finance Ministry projections suggest this year’s take will be less than 12% – showing up the limitations of the amnesty.

The shortfall can also be attributed to what Yustinus Prastowo, executive director of the Center of Indonesia Taxation Analysis, described as “quite big loopholes and opportunity for tax avoidance” in Indonesian law, as well as broader economic factors weighing on the potential tax take, such as lower prices for Indonesia’s commodity exports and less-than-expected investment.

“Theoretically, Indonesia has big tax potential represented by the total amount of the offshore assets declared during the tax amnesty programme,” Prastowo said.

Just as Indonesia is trying to balance the need for increasing revenue with concerns about deterring business, Malaysia too must balance two ostensibly contradictory demands: “increasing revenues to manage rising demand for public services” on the one hand and “keeping the tax system competitive” on the other, according to a June report by the Kuala Lumpur-based Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs.

Further highlighting the revenue challenges faced by countries in the region, Malaysia’s government under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad dialled back an unpopular 6% goods and services tax introduced by the previous government, saying his government had enough funds.

Money enough for what, though? Mahathir revisited the terms of Chinese-backed gas and rail projects commissioned by the previous Malaysian government – after first threatening to cancel the work due to cost concerns.

The renegotiation was arguably a tacit admission by Mahathir that Malaysia cannot pay for its own infrastructure improvements, as well as a reflection of US allegations that the BRI is intended to snare recipients in a so-called debt trap with China.

Mahathir himself seems aware of the supposed dangers.

“If you borrow huge sums of money from China and then you cannot pay, when the person is a borrower, he is under the control of the lender,” he told local media during a visit to the Philippines in March. “So, we have to be very careful about that.”