Michael Barr is an Associate Professor in International Relations at Flinders University in Australia. He has been researching Singapore politics and history for three decades and is the author of many books and academic articles. His latest book is Singapore: A Modern History (2019).

When Lee Kuan Yew died on 23 March 2015, it was a symbolic turning point for Singapore. For a long time, Lee had been the only prime minister Singapore had ever known. His rule went further back than Singapore’s independence in 1965, starting in 1959 when the island became a self-governing British colony, and continued through 1963–65 when it was a state of Malaysia.

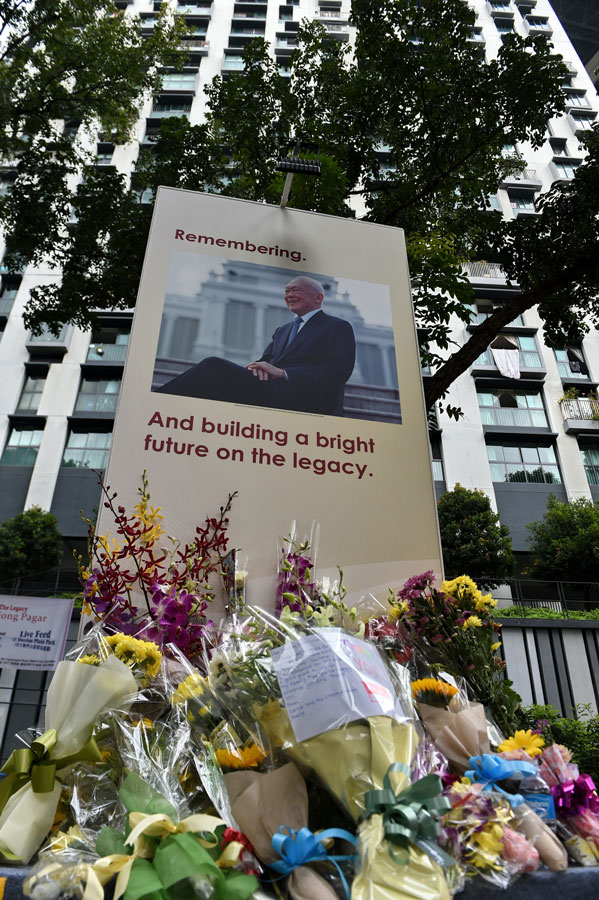

Lee was indisputably the public face of Singapore’s economic development and when he died many Singaporeans felt that they had lost a link with the past. The outpouring of grief and respect that accompanied the week of mourning culminating in his funeral was clear evidence of this, reaching dimensions that reportedly took even the government by surprise.

Yes, it was a symbolic turning point, but it should not have been a practical turning point since Lee had not been prime minister for decades. He had been succeeded by Goh Chok Tong in 1991 and Goh held the premiership until 2004, when Lee’s eldest son, Lee Hsien Loong, took over. By March 2015, Lee Hsien Loong had been prime minister for 11 years.

This is enough reason to play down the practical implications of Lee’s death, but there was another reason as well. One of the goals to which Lee Kuan Yew aspired – and which Lee Hsien Loong claimed to have achieved at the beginning of his premiership – was the creation of a seamless system of meritocratic leadership regeneration, both at Cabinet level and throughout the public sector. Lee Kuan Yew had always championed the idea that professionalism overrides politics and that politics interferes with the professional administration of government.

By this mantra, in 2015 Singapore was being ruled by the finest outcome of a meritocratic system of generational renewal that would keep Singapore ‘exceptional’, staying well ahead of the other ‘ordinary’ countries of Southeast Asia. In theory, Singapore alone was being run by the best and brightest professionals, with the best degrees from the best universities.

There is also another legacy [of Lee Kuan Yew] that I have left to last, and it is entirely positive. I refer to the successful development of the Singapore economy and the modernisation of its society

Hence one of the government’s quiet boasts in the aftermath of Lee’s death was the observation that it had no measurable effect on the markets: everything was business as usual because the system of leadership regeneration was working fine.

Except that by 2015 everything was not working fine. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had been facing severe domestic political headwinds since 2011 – new opposition breakthroughs in the parliamentary elections of 2011, the near-defeat of the government’s preferred candidate for president, also in 2011, and opposition victories in a couple of by-elections in 2012 and 2013.

To make matters worse, the political problems could not be explained away as the political cost of implementing sound policies. The PAP’s brand had been tarnished by a long series of administrative and policy failures that smacked of incompetence rather than courage or brilliance. In fact, PM Lee Hsien Loong basically admitted this when he apologised on behalf of his government for a series of failures in the final days of the 2011 General Election campaign.

And who can forget former prime minister Goh Chok Tong’s 2011 election speech, in which he defended the record of one of his Cabinet colleagues by saying that he was not nearly as incompetent as some of the others? Incompetence was not supposed to be the outcome of a meritocracy, and yet the evidence was too powerful to ignore, whether we consider housing, health, hospitals, cost of living, reliability of public transport or immigration.

With these developments so recently in the background, questions were already being asked about the longevity of Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy at the time of his death and yet the public response to his death showed that it was just the government’s brand that had been trashed by incompetence, not his. Lee Kuan Yew’s personal brand, and that of his family, in fact, reached new heights in 2015, becoming the centrepiece of Singapore’s 50th anniversary celebrations (SG50) later in the year, and helping Lee Hsien Loong recover some lost ground in the 2015 General Elections.

Family feud

Five years have now passed since Lee’s death and there has been one development above all others that has caught Singapore-watchers by surprise – Lee’s children and grandchildren have managed to trash the family brand in an unseemly squabble over his legacy.

The focus of their dispute is Lee Kuan Yew’s will, in which he left instructions concerning his family home. Lee Hsien Loong claims his father wanted it maintained as a monument. His younger brother and sister, Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling, say he wanted it bulldozed once Lee Wei Ling had finished living in it, which was expressed in his final will. Not so, says Lee Hsien Loong, because that final version of his will was the product of manipulation by Lee Hsien Yang and his wife Lee Suet Fern (a senior lawyer).

So keen was Lee Hsien Loong to prove his point that he used parliament to attack his siblings and established a committee of his ministerial colleagues to investigate them. Then the Attorney General’s Chambers referred Lee Suet Fern to the Law Society claiming that she manipulated a senile and confused Lee Kuan Yew into changing his will. (The Attorney General, Lucien Wong, was formerly Lee Hsien Loong’s personal lawyer.)

All this was played out against a background of Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling going public through Facebook and the international media in accusing Lee Hsien Loong of trying to set up a ‘dynasty’ by positioning his son, Li Hongyi, to be a future prime minister. This has since been followed by accusations that Lee Hsien Loong was abusing his power as prime minister to win a family dispute and Lee Hsien Yang has taken to associating his name with opposition parties and funding civil society activists who are being attacked by arms of government.

At the time of writing we are still waiting to see if Li Hongyi will stand in the forthcoming General Elections, but we are consoled by Lee Hsien Loong’s assurance that any question of an abuse of power has been dismissed by parliament. In the meantime Lee Hsien Yang’s son, Li Shengwu, is effectively a refugee in America, having been charged by the Attorney General’s Chambers with contempt of court for a Facebook post.

This is not the legacy Lee Kuan Yew would have wanted or could have anticipated. It is demeaning and grubby – and has damaged the Lee family brand irrevocably. It remains to be seen if it has enough life to survive to a third generation, but even if it does, it is not what it was and never will be again.

By contrast, Lee Kuan Yew’s personal brand is probably secure. In fact, the contrast between his seriousness and professionalism and the recklessness and seeming pettiness of the next generation may even have enhanced the rosy colour in the glasses that people seem to wear these days when remembering ‘the old man’.

The rise of the mediocracy

Lee Kuan Yew did what he could to determine the trajectory of his family legacy, but it was not enough. Such is the lot of any patriarch post-mortem. There is, however, a more important flaw in his political legacy that has become obvious in the last year, and which is very much down to him. I refer to his dream of a seamless system of meritocratic selection of Singapore’s leaders.

The problem is that even though he believed in meritocracy and was presumably at some level genuine in wanting to end privilege due to accidents of birth or favouritism or personal bias, Lee could not stop himself from corrupting his own creation.

He created an elite education and elite-selection system that privileged Chinese children from the upper-middle class. He used the arms of state power and state-linked enterprise to build networks of patronage staffed by people loyal to him personally, and to his family. All his children had unique opportunities to excel on a playing field that was anything but level, and one of them ended up as prime minister. In short, he set up an entire ecosystem in which personnel selection at every level – but especially at the highest levels – was determined by accidents of birth, favouritism and personal bias.

Five years after his death, Singapore’s aspirational meritocracy has settled into a comfortable mediocracy. Talent can rise a long way, but with the right patron, the mediocre can rise all the way to the top.

The political and administrative challenges of 2011 were a direct consequence of this system of mediocracy. Since then, the country has been watching how life under a mediocre government unfolds, and Singaporeans have lowered their expectations accordingly. Now a new generation of leaders is stepping up to the front line in the Cabinet, and there are clear signs of worse to come.

The next generation of Singapore’s political leadership is proving itself adept in just one field of governance – control of information and repression of dissenting voices. In this they are excelling in the age of social media, which is no mean feat. This achievement will most likely keep them in power for years, but repression of dissent is not an indication of excellence in government – rather it is the refuge of governments of all stripes who place the highest priority on political longevity.

State capitalism

Lee may have missed his chance to build a legacy in the field of good governance, but there is one major field of global significance where he truly was innovative, and which may yet be a positive example. I speak of his government’s experiments in state capitalism.

Lee and his colleagues built on a hundred years of experimentation with state-driven and state-guided capitalism in places like Japan and Germany and developed the world’s best practice in the field. They found a formula that mixed professional management techniques with state-linked management and ownership and did so without producing an unsustainable rentier political economy.

Singapore may not have truly gone from Third World to First, as Lee Kuan Yew claimed, but under his leadership, a colonial port city was transformed into a successful global city in the space of half a century

This achievement is a dream come true for authoritarian regimes, and indeed Singapore has found a willing student of this model in China. Yet no one should imagine that Singapore’s Government-Linked Companies are perfect, or that their professional decisions and appointments are free of the effect of patronage and politics.

We also cannot assume that the experiment is going to ‘win’ in the sense of outliving or outperforming systems of private and managerial capitalism, but at least the model has outlived its creator, and is thus far showing no signs of collapse.

A legacy in perspective

There is also another legacy that I have left to last, and it is entirely positive. I refer to the successful development of the Singapore economy and the modernisation of its society.

There are a lot of myths and exaggerations about Lee Kuan Yew’s role in Singapore’s development that make it difficult to get a clear picture – not least of which was that he took Singapore ‘from Third World to First’ all by himself. Yet even dismissing the exaggerations (e.g. Singapore was never ‘Third World’), let us acknowledge that his service to Singapore was impressive and would make a proud record for any politician.

Singapore may not have truly gone from Third World to First, as he claimed, but under his leadership, a colonial port city was transformed into a successful global city in the space of half a century. The government today is stable and mostly efficient, if not democratic or ‘exceptional’. Free speech is not respected, and political opponents get bullied and sometimes jailed, but neither is Singapore a brutal dictatorship or a totalitarian state.

This record could have easily been very different, and it is substantially thanks to Lee Kuan Yew that Singapore is today the success story that it still is. Some of his and his hagiographers’ other claims to immortality may be overblown, but this more basic reality should be sufficient to guarantee Lee Kuan Yew a place of honour in the history books.