Thai student activist Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal began receiving strange messages in May offering him money to dissolve the publishing company he had worked so hard to create. He ignored them, assuming it was a scam, or an elaborate piece of trolling. After all, he was used to this kind of attention after years as a prominent pro-democracy activist.

Netiwit has been a household name in Thailand since his high school days, when his campaigns to reform the country’s archaic education system made national headlines. He then founded Sam Yan Press while studying political science at Bangkok’s prestigious Chulalongkorn University, working overtime to publish dozens of titles on topics as varied as civil disobedience, socialism, urban planning and veganism.

His student-run company has sold thousands of books across the country, helping to nourish a political awakening amongst Thai youth that would blossom into the mass pro-democracy movement of 2020-2021. But now someone was offering him a bribe to shut it all down, which a statement posted on the Sam Yan Press website said “posed a serious threat to our independence, security, and freedom of expression”.

Netiwit has been a thorn in the side of the Thai establishment for years. For his activism, he has suffered harassment, legal charges and expulsion as head of the university’s student council. But as much as it would please the Thai government and their conservative supporters to see the end of Sam Yan Press, it was not them trying to close it down. According to Netiwit, it was a Chinese citizen who wanted rid of the publisher.

The attempt to bribe Sam Yan Press symbolises anxieties over the often corrupting effects of China’s growing wealth and influence in the region. For Netiwit and his peers at Sam Yan, taking the bribe would have been an acceptance of China’s increasingly authoritarian reach, and they were not willing to give an inch.

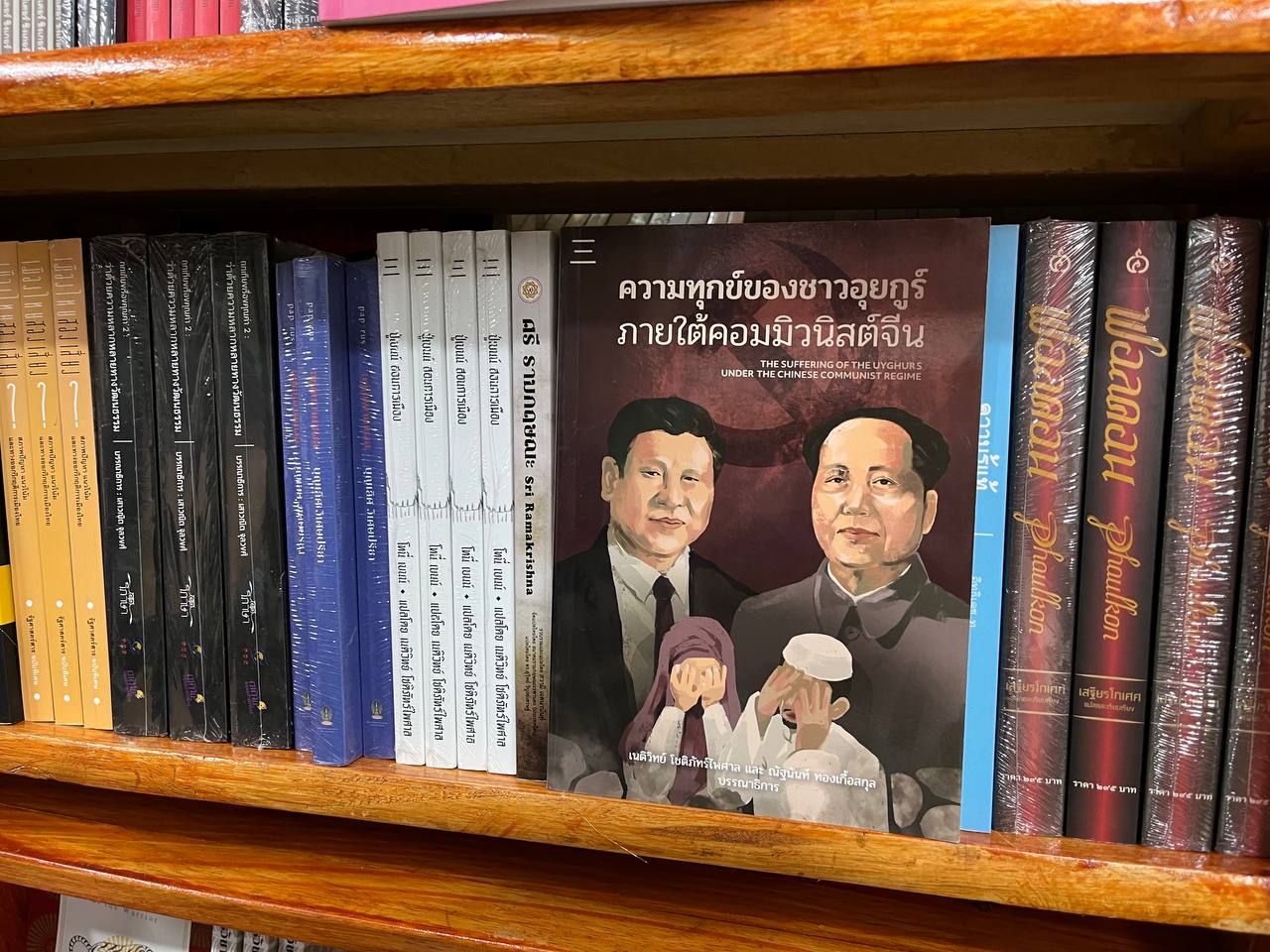

Since it launched in 2017, Sam Yan Press has maintained a special focus on China, publishing books on topics considered highly sensitive by the Chinese regime, like the Hong Kong protests, the status of Taiwan, and policies towards Uyghurs in Xinjiang. And it would appear to Netiwit and his team that the Chinese Communist Party would prefer these hot button issues not be discussed, even by a small, student-run book publisher in Thailand.

The first contact came by email, from a Thai private agent who said he represented a Chinese businessman based in Thailand. When Netiwit failed to reply, the private agent tried again by phone, laying out the offer. His Chinese client would give Sam Yan Press the considerable sum of $55,000 (2 million Thai baht), if they agreed to close down the business.

Netiwit and the small team who run the company decided to ignore the dubious proposal. Yet the private agent persisted, sending more messages, then finally showing up unannounced at the young activist’s home.

Feeling infringed upon, the Sam Yan Press team arranged a meeting at a Starbucks near their university, to resolve the matter once and for all. There, the private agent spent an hour trying to persuade them to accept the money and close down their company, which he said would help his client win favour with the Chinese government. Sam Yan Press politely declined, explaining that it would go against their principles.

“The Chinese Communist Party’s leaders are most concerned with how the government is viewed within China itself,” said Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a historian of modern China at the University of California, Irvine. “But it also does pay attention to its global reputation and is eager to be seen in a positive light, especially in the region and among members of the Chinese diaspora.”

With around 7-10 million people, the Chinese diaspora in Thailand is the largest in the world. On a recent trip to Thailand for the APEC summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that “China and Thailand are as close as one family.” But ethnic Chinese identity in Thailand is complex and personal. With fewer barriers to integration than regional neighbours like Malaysia or Indonesia, the Thai-Chinese have been free to either cherish or shed their Chinese-ness over the generations.

Netiwit, whose grandparents came to Thailand from Guangdong, seems to lean into his Chinese ethnicity. His nickname, ’Franky Qin’, is a shortened version of his Chinese name, Qin Lian Feng. But he represents a younger generation of Thai-Chinese who have a less favourable view of China than their parents and grandparents. Cosmopolitan and progressive, they prefer the cultures of Hong Kong and Taiwan, which they see as more open than the mainland. It’s not that they deny their Chinese identity, but that they reject the authoritarianism of the Chinese Communist Party, and are wary of its influence in the region.

This sentiment has grown in recent years. Sales of Sam Yan’s first book, about Hong Kong protest leader Joshua Wong, were poor. The political stand-off between China and Hong Kong seemed too far removed from life in Thailand for people to worry about. But as young Thais watched the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests unfold online, their feelings started to change. This led to the ‘Milk Tea Alliance’ phenomenon; an online transnational democracy movement comprising Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Suddenly, the issues Netiwit had been talking about for years became more mainstream, and interest in Sam Yan Press publications spiked.

The Chinese Embassy in Thailand issued a tetchy response to the Milk Tea Alliance on its facebook page, reaffirming the “One China” claims of sovereignty over Taiwan and dismissing “the recent online noises” as “bias and ignorance.” Bellicose statements are common from Chinese officials, but this is only one of the ways they attempt to enforce China’s narrative beyond its borders.

“The Chinese government maintains extensive networks of assets and co-optees around the world, and Thailand is unlikely to be an exception,” said Alex Joske, author of Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World. “These contacts can be involved in a range of activities, including political influence work designed to suppress opposition to China and advance pro-China positions.”

It’s hard to know if the attempt to close Sam Yan Press was orchestrated by these networks, known as the United Front, or just one overzealous Chinese citizen acting independently. But Joske notes that “suppressing foreign dissident organisations has been a top priority for the Chinese Communist Party in recent decades, and the Sam Yan Press case fits that general pattern’.”

The incident is “unusual but not completely isolated,” Wasserstrom added. His book, Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink was translated into Thai by Sam Yan Press. “One could see it as part of a pattern that includes efforts to block showings of a film critical of the Chinese Communist Party and discouraging universities in different parts of the world from putting on events featuring dissidents in exile.”

Although the dealings between Sam Yan Press and the private agent were cordial, the situation left them feeling on edge.

Jirapreeya Saeboo, the publisher’s managing editor, said the decision to go public about the incident was for their safety. Pointing to the website of the private agent company, Sky International Legal, she notes that bodyguard protection and debt-collecting are listed among the services it provides. It’s an unsavoury world that the 21-year-old student would clearly prefer not to be mixed up in.

Recent headlines of Chinese organised crime operating in Thailand might have added to Jirapreeya’s concerns. A series of ongoing investigations and high-profile raids have revealed an alleged network of Chinese organised crime in the country, with deep pockets and potential links to well-placed Thai officials. Elsewhere, such networks have been known to assist the Chinese Communist Party with its agenda.

“In countries such as Australia, Canada and Taiwan, alleged organised crime networks have documented overlap with United Front organisations,” Joske said. “As former Chinese Minister of Public Security Tao Siju reportedly said, ‘organised crime can be patriotic’ – the Chinese Communist Party appears to be happy to work with criminal organisations as long as their interests are aligned.”

But the potential risks don’t deter Netiwit from his goal of building his own progressive transnational networks in the region. “Dictators learn from each other, adopting the same mechanisms of control and fear,” he said. . “But we can learn from other activists, too. We can learn about their tactics, their ideas, their spirit…about why they risk their lives, and about what type of society they want to make happen.”

The solidarity from Thailand is well-received by Hong Kong activists as well. Alex Chow, a prominent leader of the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement that saw tens of thousands of protesters take to the streets, said “gaining transnational allies such as the Thai people reaffirms the moral cause of Hong Kongers who are fighting for freedom and democracy.”

Another core leader of the Umbrella Movement, Nathan Law, adds that people in Hong Kong are “very thankful” that Thais pay attention to their struggle. Like so many who took part in the Hong Kong protests, Law left his home to avoid reprisals from the Chinese government, and now lives in the UK. “The support from outside means a lot to us when it’s difficult to protest inside Hong Kong,” he said.

The name ‘Sam Yan’ refers to the Bangkok neighbourhood where the publisher is based, and alongside the big, far-reaching issues like authoritarianism in China, Netiwit and the team find time to highlight smaller, more local concerns.

Earlier this year, they published an oral history of the life and memories of ‘Aunt Tiw’, a Thai 70-year old cook who has spent much of her life at Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Political Science. The book, which Aunt Tiw said she is “proud and pleased” to be part of, shows how the university and the country have changed over the decades, as seen through the eyes of an ordinary person.

Still at the draft stage is a book on the plight of a 150-year old shrine built by Thai-Chinese immigrants, which sits on land owned by Chulalongkorn University. The shrine and its caretaker, 44-year-old Penprapa Ploysrisuay, are embroiled in a protracted legal battle with the university, who want to evict her and demolish the shrine to make way for a new high-rise development.

Netiwit has been helping Penprapa raise money and amplify the cause. “Frank is full of kindness,” she said about Netiwit, using his nickname. “Without his help, nobody outside the community would know about what’s happening with the shrine.”

Not long after turning down the money to close Sam Yan Press, managing editor Jirapreeya is busy packing up mail orders, which have poured in after media coverage of the incident. The small office space Sam Yan Press rent is decorated with pictures of Martin Luther King, Joshua Wong, and a Tibetan flag.

A bust of the iconic 1950s-1960s Thai activist, Chit Phumisak, sits on a well-stocked bookcase. As she places the orders into the mailers, Jirapreeya admits that the offer of such a large amount of cash was “alluring.” Sam Yan’s finances are precarious, and with money still to recoup from previous editions, the company is stuck with a backlog of new titles they can’t afford to print.

But Aunt Tiw said the attempt to bribe the publisher was wrong, and the team should “keep fighting.” Whether it’s in their local community in Sam Yan, or further afield in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Netiwit and Sam Yan Press are promoting causes they believe in, and which are often underrepresented.

“I look around and I see the silence of the Thai media on the suffering of Uyghurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongers, and I don’t want to be like that,” said Netiwit. “We are proud that our small publishers have contributed to changing the attitude of young Thais on these topics. It is worth staying true to our principles. The work we have done is priceless compared with money.”