On Thursday, the road across from the Indonesian Presidential Palace in Jakarta filled with about 200 protesters dressed in black.

As they and others before them have done for 760 consecutive Thursday afternoons, the protesters had gathered for the weekly Kamisan event – an ongoing call for justice for the victims of human rights violations in Indonesia, driven by their surviving family members. The protests, which started in 2007 in the capital Jakarta but are now conducted in 60 Indonesian cities, marked their 16th anniversary this week.

“The protest helps shed a light of truth and righteousness in a tunnel of darkness, even in the narrow path towards justice,” said activist Maria Catarina Sumarsih during the most recent Kamisan.

Sumarsih, 70, is a founding member of the protests. The mother of a student slain by the Indonesian National Armed Forces in a 1998 mass shooting known as Semanggi I, she stood out in the mostly youthful crowd during Thursday’s event. Silver-haired and straight-backed, she walked with vigour among other activists who offered gestures of respect, some even kissing her hand.

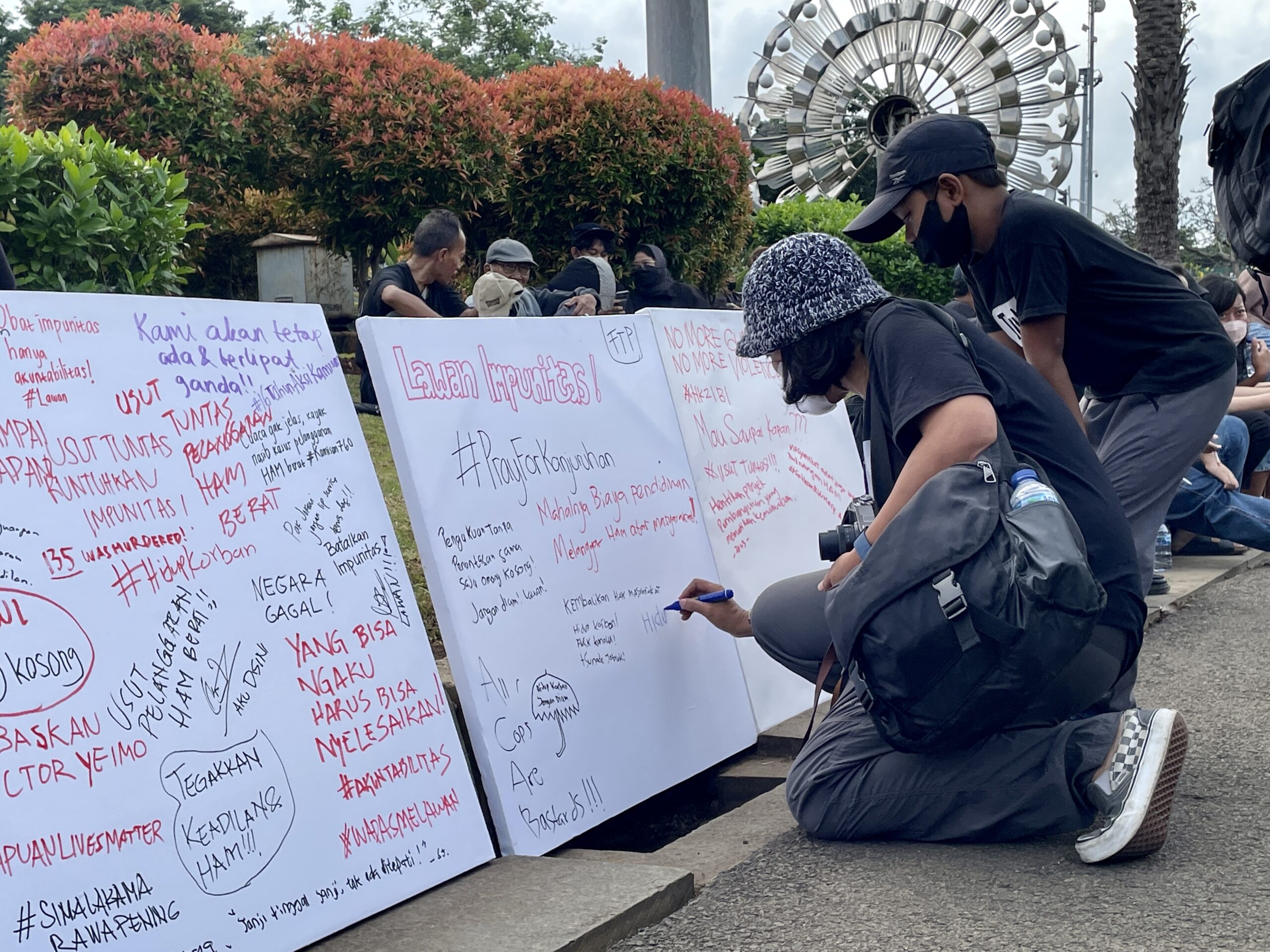

The protesters had gathered in front of the National Monument by the palace. They carried black umbrellas and chanted “Hidup korban!”, “Jangan diam!” and “Lawan!” – Indonesian for “Long live, victims”, “Do not be silenced!” and “Resist!”.

Initially inspired by the vigils of Madres de Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, the events are simply named for the Indonesian word for Thursday. Supported by the civil society group Jaringan Solidaritas Keluarga Korban (Family of Victims Solidarity Network), Kamisan demonstrators have rejected government suggestions for non-judicial resolutions for past human rights abuses. That strategy is currently being pursued by President Joko Widodo, who on 11 January made headlines by acknowledging the state’s past abuses but stopped short of apologising for them.

Among the dozen human rights violations mentioned by the president are the the 1965 killings of upwards of 500,000 people during the country’s anti-communist purge and the disappearances of pro-democracy activists in 1997-98, as well as the mass shooting of protesters by soldiers at Trisakti University and in the massacres known as Semanggi I and II. Widodo also included the murder of human rights activist Munir Said Thalib, as well as the case of the 2014 mass shooting in Papua often referred to as “Bloody Paniai”.

Vincent Bevins, author of the book The Jakarta Method about the U.S. role in the mass killings of communists in Indonesia, said Widodo’s acknowledgment of these atrocities was a significant move.

“The consensus view (of the survivor community) was that this was a step forward, but not far enough,” Bevins said. “It should be recognized that this was an important day for Indonesia, but it should also be recognized that Indonesia is far behind other countries that were host to egregious human rights and comparable crimes.”

Citra Referandum, director of the legal aid group LBH Jakarta, saw this stunted progress as a result of political intransigence.

“Indonesia lacks the political will to take accountability to resolve its past human rights violations,” Referandum said. “In its practice, the government instead perpetuates impunity and utilises its own laws to deny the people’s rights to restoration and a fair and honest judicial system.”

During the campaign for Widodo’s first term as president in 2014, he had promised to fight impunity. But the Kamisan protesters and other rights activists say the president’s actions have not delivered on those words, pointing to his administration’s inclusion of former high-ranking military officials connected to past rights abuses.

These include Wiranto, a retired army general. In 2004, the UN-backed East Timor Tribunal charged him with crimes against humanity allegedly committed in 1999. Wiranto, who goes by one name, had been the commander-in-chief of the Indonesian National Armed Force and the minister of defence during the East Timorese struggle for independence. Still, in 2016, the Widodo administration appointed Wiranto as the coordinating minister for politics, law and security affairs.

“The statement from the president in which he acknowledged past human rights violations means nothing without holistic legal accountability,” said Usman Hamid, executive director of Amnesty Indonesia. “The government also needs to apologise and make sure that such violations will not repeat itself in the future.”

Hamid pointed to Wiranto’s additional role as the chair of the Advisory Council of the President – as well as the appointment to minister of defence of Prabowo Subianto, another former general accused of atrocities in East Timor and rights abuses against student activists – as undermining Widodo’s statements.

“I doubt the remaining time in his presidency will be enough to resolve the violations he just admitted,” Hamid said.

For now, Widodo’s approach has centred on a presidential decree pushing for non-judicial resolutions to past abuses. This would eschew convictions of the accused and instead offer victims and their relatives physical rehabilitation, social aid, health insurance and other methods to aid recovery.

Sumarsih and other families of victims refuse to accept that.

“We continue to call for a resolution that complies with the Indonesian Constitution. Hold an ad-hoc human rights court, and hold those accountable through judicial means,” said Sumarsih. “If our demands had been met, then there would be no Kamisan.”

Sumarsih continues her activism in memory of her son, 20-year old Bernardinus Realino Norma Irawan, who was known by his nickname Wawan. At the time of his death, he was a student at Universitas Atma Jaya during the transition period between Soeharto’s New Order regime and the Reformation period of democratisation.

Wawan and other student activists had demanded the new presidential cabinet be purged of non-elected military members. During a protest on 13 November, 1998, soldiers opened fire, killing 17 people. Wawan was one of them, shot in the chest while trying to help another victim.

“I saw him as he lay in the morgue. His eyes closed, as if he was sleeping,” Sumarsih recalled.

Sumarsih never found out the identity of his son’s killer. Her frustrations led her to Kamisan, where for the past 16 years now she’s shown up every Thursday at 4 PM to demand justice.

She might be just one of many who lost loved ones to major human rights violations in Indonesia, but the deeply religious Sumarsih does not give up hope.

“Every day since the passing of her son, one prayer remains the same: ‘I pray that the heart of my son’s murderer will be touched by [God’s] divine love,’” she said.