“I’d never thought someone would adapt the book into a film,” award-winning British foreign correspondent Jon Swain told the Globe. “It’s a very thrilling experience – it’s a wonderful, positive and uplifting thing to happen.”

The book in question is Swain’s 1997 memoir, River of Time: A Memoir of Vietnam and Cambodia. In June, it was announced that screenwriter Lawrence Osbourne would adapt Swain’s memoir for the silver screen, to be produced by Bangkok-based Indochina Productions.

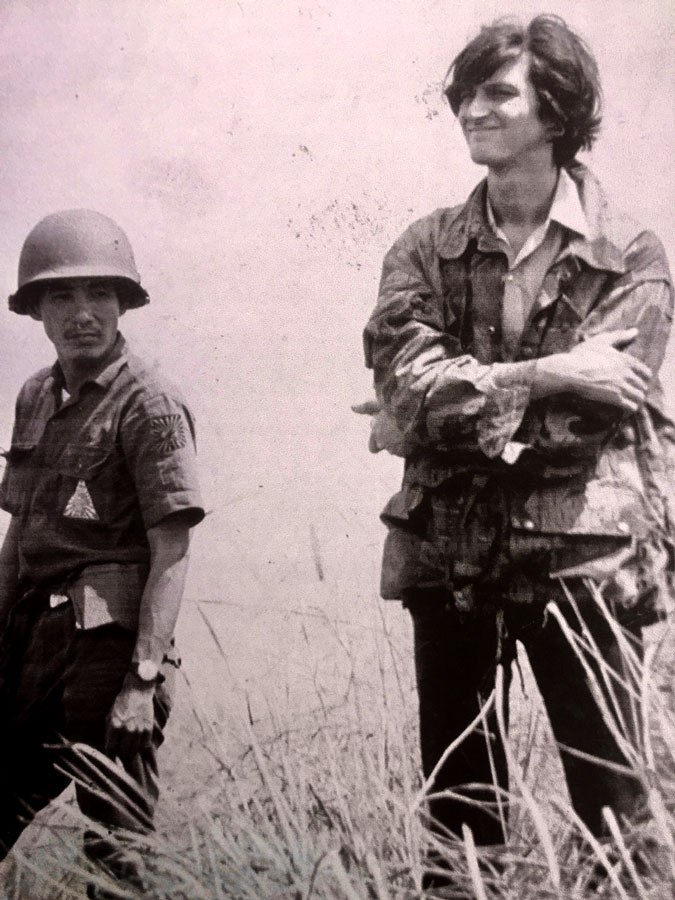

Swain, a former Agence France-Presse (AFP) and The Sunday Times correspondent, is known best for his award-winning work in Cambodia and Vietnam, which won him the 1975 British Press Awards Journalist of the Year.

Like the Mekong River, which plays a significant role in the book’s narrative, the memoir traverses Swain’s time through Indochina, between 1970-1975.

From the civil war in Cambodia to the American war in Vietnam to the fall of Phnom Penh, River of Time is less memoir, and more a glimpse into a period of intense upheaval and horrific violence. “My hope is that it can introduce and deepen peoples’ understanding of what happened,” said Swain. “Hopefully it can open their eyes that little bit more.”

I’d become incredibly attached to Cambodia, but in Vietnam the much bigger war was raging – it was the biggest story in the world

After a stint working in London, Swain crossed the Channel to Paris in his early 20s to occupy one of the three roles AFP had set aside for English-writing journalists. But he still held ambitions to go farther east.

“I developed this early romantic fascination of Indochina,” said Swain. “As a 22-year-old, it ticked all the boxes for what I wanted to do.”

Swain made this desire clear and, coincidentally, the French AFP correspondent in Phnom Penh was soon expelled, leaving a position to be filled. Considering the expulsion, the agency thought it best to change tack.

“They thought, ‘It may be safer not to send another Frenchman, let’s send someone else,’” remembered Swain. “That someone else, was me.”

He rushed to get a plane ticket bound for Phnom Penh on the next day and, in his excitement, promptly lost it, launching his journey with an inauspicious start.

“I thought to myself, Jesus Christ, they’re going to think ‘Why on earth are we sending this guy! He can’t even make it to the airport!’”

A replacement ticket was printed, and Swain boarded the flight without further hiccup. The flight was bound not just for Phnom Penh, but a five-year-period of love and war, and a devastating upheaval that would shape not only the region, but also the young journalist.

In River of Time, Swain describes his relationship with Cambodia as a beautiful love affair: ‘[A] stunning woman who overwhelms you and you can never quite understand why – who you lose your heart to, and lures you back again and again.’

He said that upon arrival in Phnom Penh in 1970, he was engulfed by the city.

“There was an ambiance of sensuality and this fantastic collision of ‘Frenchness’ with local Cambodian exoticness,” remembered Swain. “It was absolutely mind-blowing.”

For the newly arrived journalist, Phnom Penh proved to be one of those cities that grabs you, and never lets you go. A bustling journalistic scene, nightlife and an abundance of opium proved to be an awakening of the senses.

“You could jump into a cyclo and be whisked away to where you wanted to go – whether that be out for dinner or off to smoke some opium,” remembered Swain. “I felt as if anything and everything was possible.”

The Mekong river, so integral to the region, played an equally important role in Swain’s time in Cambodia. “Some rivers are so placid, they don’t move you – the Mekong was different,” said Swain. “I encountered life and death beside it.”

While reporting on the civil war ravaging the country, it was on the banks of the Mekong that Swain experienced the thin line between life and death – a soldier killed by Vietnemese insurgents. “It was there, in 1970, at Neak Loeung, that I saw my first dead body,” said Swain.

During his time in Cambodia, Swain wired back stories of the civil war, of Lon Nol’s slowly disintegrating Khmer Republic, insurgencies from the Vietnamese and the enigmatic, fledgling Khmer Rouge.

In 1970, a grenade attack at one of the city’s cinemas prompted Swain to help a wounded girl, rather than wire back the story to the AFP. He eventually did so – late – and was reprimanded by his bosses. They did, however, sign-off with a single word – courage.

At the turn of 1971, however, Swain’s visa was revoked, and his time in Cambodia along with it. Swain never found out why, but believed it to be for filing a contentious story about the communist occupation of the French rubber plantations. But a position across the border in Vietnam opened up, and the journalist was to swap one love affair with another – but this time, it wouldn’t just be with a city.

“I’d become incredibly attached to Cambodia, but in Vietnam the much bigger war was raging – it was the biggest story in the world,” said Swain. “And from a personal perspective, I sort of hoped I’d meet again the girl I really fancied – Jacqueline.”

Swain had met Jacqueline while in Phnom Penh, but it was to be in Saigon that their love blossomed and they would live out their love amid scenes of war.

Describing it as “one of those cities that burn into your consciousness the moment you arrive”, Swain arrived in Saigon, swapping one war for another. The country would entrench itself in Swain’s heart, much like Cambodia had. “Both of them, gradually, took over my soul.”

During the course of his stay in Vietnam, Swain would file stories of untold destruction and suffering – the American war in Vietnam, assaults along the Ho Chi Minh trail and the deployment of Agent Orange.

In 1973, with the Paris Peace Accords signed, he travelled to Vietnam’s Central Highlands to see for himself what ‘peace’ actually looked like. In ‘peacetime’, it seemed that the death only continued.

“I was with this man and thought what a terrible waste of life this all was,” remembered Swain, referring to a South Vietnamese soldier, badly wounded and bleeding to death. “It was a chronic war and it led to untold misery.”

The passing of time, like a meandering river, cannot stand still. And across the border in Cambodia, as the new Republic’s regime was about to topple, one was to emerge from its embers to inflict horror onto the Kingdom’s people.

In April 1975, with the fall of Phnom Penh imminent, Swain had a choice to make – either stay in Saigon with his life and love or return to the city that had made such an impression, reporting from its walls as they collapsed around him.

“It was very much a personal decision, a sense of being propelled by some inner force,” explained Swain. “Cambodia had really penetrated me – it had given me so much – and I had been there at the start, and I felt I had to go and be there at the end.”

Swain took the decision to leave Vietnam and return to Cambodia. His visa, stamped into his passport in the embassy in Saigon, was the last issued of the Lon Nol regime he said; as everyone else was catching the final plane out, Swain was catching the final one in.

After arriving in Bangkok, Swain knew that there was one last flight scheduled for the following day, but questioned if he could go through with the journey. “I looked at myself in the mirror and thought, did I have the balls to go through with this?”

Swain flew into a Phnom Penh on the cusp of disaster on April, 13, 1975 to a place far removed from the city he knew in 1970, just four days before the Khmer Rouge would overrun the capital in the Fall of Phnom Penh. A few hours before his flight, the US had closed its embassy and evacuated all of its staff, bringing to an end its five-year involvement in the Cambodian civil war and paving the way for the Khmer Rouge to take control.

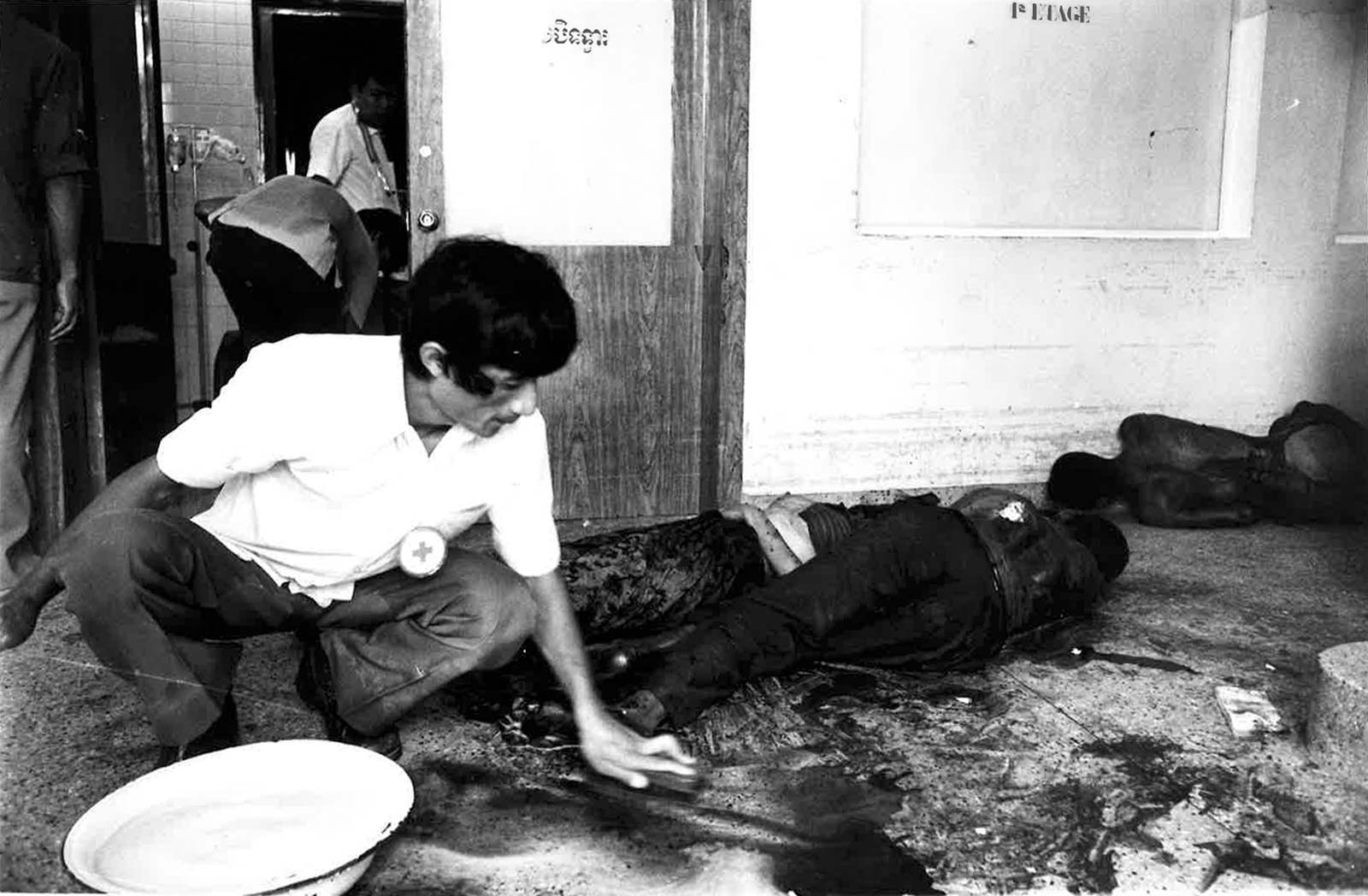

Hospitals were overflowing, the displaced were in their thousands and an uncertainty of what came next filled the air. Red Cross personnel had commandeered the Hotel Le Phnom – now Raffles Hotel Le Royal – while the only way to file stories was through the sole transmitter, based in the city’s post office. “It was extremely frightening,” said Swain.

The civil war was over, but the supposed peace was a mere placeholder for what the Khmer Rouge would inflict upon millions of Cambodians. “We knew about the Khmer Rouge to an extent, but they were still a mysterious body,” said Swain. “We knew how brutal they were and had heard stories of their massacres, but it was hard to pin down specifics. But we were aware that the war wasn’t going to end in a pretty way.”

When the Khmer Rouge conquered the city, Swain described scenes of people streaming out of houses along boulevards, in what was the start of the mass deportation of the city’s inhabitants into the countryside to kickstart the Maoist’s despotic revolution. “We became increasingly frightened of a danger that we couldn’t fully comprehend,” said Swain.

Now immortalised on screen in 1984’s The Killing Fields, Swain, alongside The New York Times correspondent Sydney Schanberg and his local fixer, Dith Pran, encountered first-hand the capacity for violence the Khmer Rouge possessed, in a near-death experience along the banks of the Mekong.

After visiting an overflowing hospital in the city’s centre, the three of them were pulled over by half a dozen soldiers, “bristling with guns and some perhaps twelve years old, hardly taller than their tightly held AK47 rifles”, Swain recounted.

They were thrown into the back of a van, driven through the city before being hurled out by the banks of the Mekong, rifles locked, loaded and aimed. The river, again, leaving its water mark on Swain’s life. “We were sure this was the journey’s end; we would be executed and our bodies tossed into the Mekong,” said Swain.

They would be saved by Pran, convincing the executioners that the journalists came to cover the ‘glory and success of the Khmer Rouge’s revolution’, and that killing them would be counterproductive.

Rifle to head, seemingly destined for execution and only saved by Pran’s skills of persuasion, it is a spot that Swain returns to each time he visits Phnom Penh. “I go not just for myself, but to try and remember all of those in the city at the time and what it was like for them,” said Swain.

At one point they had to drink from the air-conditioning units … they had to catch, skin and eat the ambassador’s cat

While the Khmer Rouge went about tearing the city down, Swain was holed up for near two-weeks with hundreds of others in seemingly the only safe place in the capital – the French Embassy.

In River of Time, Swain vividly depicts the ordeal – how eventually the Khmer Rouge forced out the few Cambodians hiding alongside them, how at one point they had to drink from the air-conditioning units, how they had to catch, skin and eat the ambassador’s cat. “You were living minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour, day-by-day,” said Swain.

With no means to transmit stories and with the Khmer Rouge starting to seal the country off, Swain couldn’t report from Phnom Penh, but his journalistic tendencies didn’t wane. “I didn’t realise at the time just how big this story was,” admitted Swain. “But I collected what I heard, to eventually tell the world what had happened in Phnom Penh.”

The holed-up group were finally allowed to leave and were taken in open lorries to the Thai border. Swain was apprehensive. “We were uncertain whether we were going to actually make it to Thailand – we were given assurances, but of what value?”

The normally 10-hour journey took four days, and as they drove out of the city-limits, the mass desertion of the capital dawned on Swain. “Where had everyone gone? Where had almost two million people disappeared to?”

Once they had reached Thailand, Swain could but only remember those left behind, that would be sealed into a black hole as the Khmer Rouge cut ties to the rest of the world and went about building a warped utopia – a utopia believed by some estimates to have killed almost 2 million people, roughly 25% of the country’s population.

Living in Bangkok, Swain would visit the Thai-Cambodian border some months later and from a vantage point, peered down into the country. “I looked over the paddy fields and saw nothing – absolutely nothing,” remembered Swain. “It was as silent as a grave and I couldn’t fathom what had happened.”

The Khmer Rouge’s rule and killing fields are well documented, serving as proof of the savageness of humankind.

“At the time, it was absolutely horrific,” said Swain. “Hospitals were overflowing, families were torn apart, there were hundreds of thousands of refugees, children were incredibly thin – there was no end to it.”

But Khmer Rouge rule did end, and the Cambodia that Swain often revisits today – although not the one he hoped would emerge – has rebuilt itself.

“There’s a lot of things that Cambodians themselves will think are terrible [about modern-day Cambodia] – rampant corruption and terrible inequality,” said Swain. “I love the country and its people, but it breaks my heart to see that.”

For Swain, every visit to the country that stole his heart is like revisiting a childhood home, but the furniture, people and places are not the same.

“The Khmer Rouge rule lasted four-years, millions died, thousands are now widowed – I can only pay tribute to their endurance – the resilience of the Cambodian people,” he said. “The fact the country still exists after everything that happened, it’s a miracle.”