If every cloud has a silver lining, then the smog-free city skies of the coronavirus era could take on a new shine.

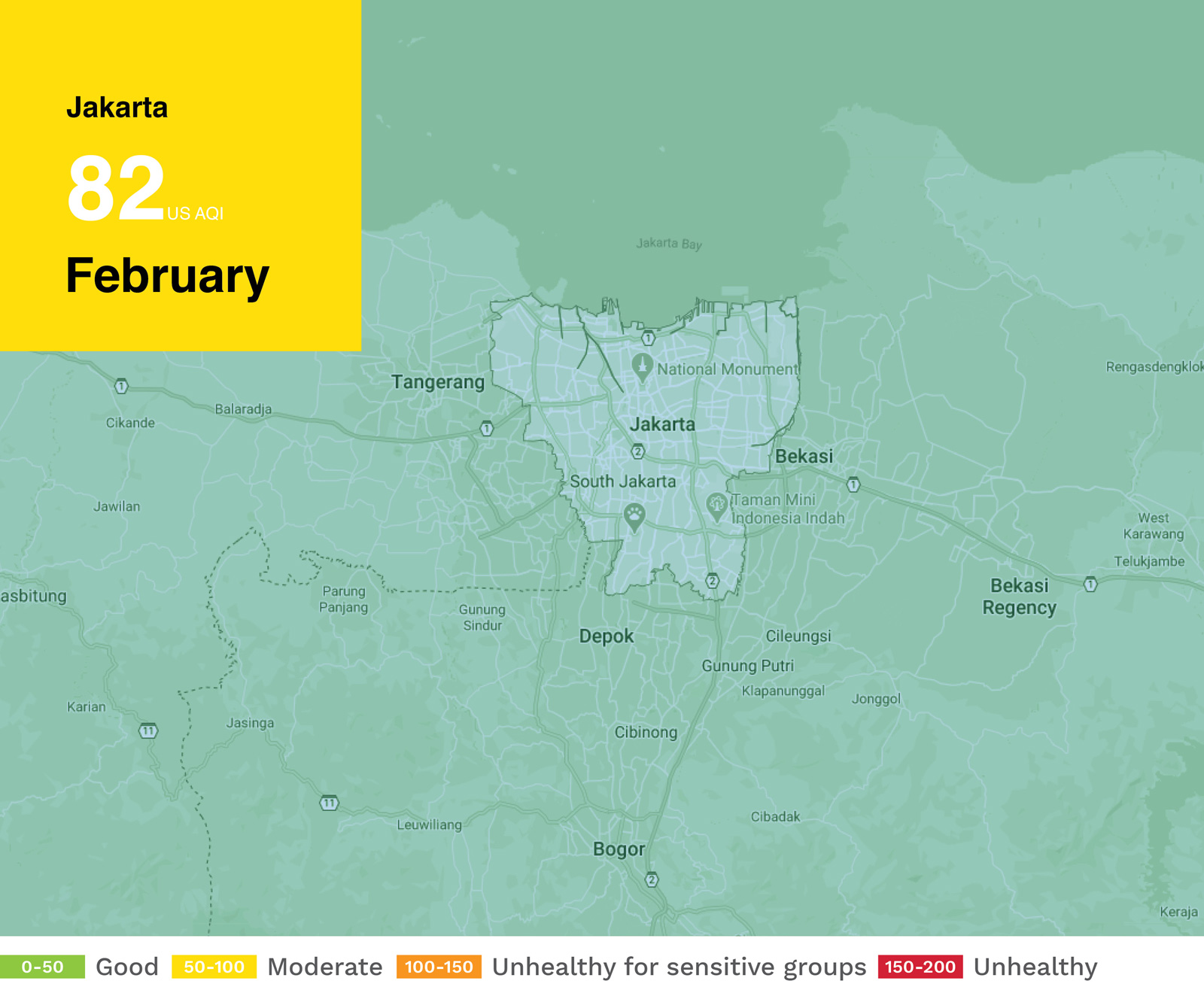

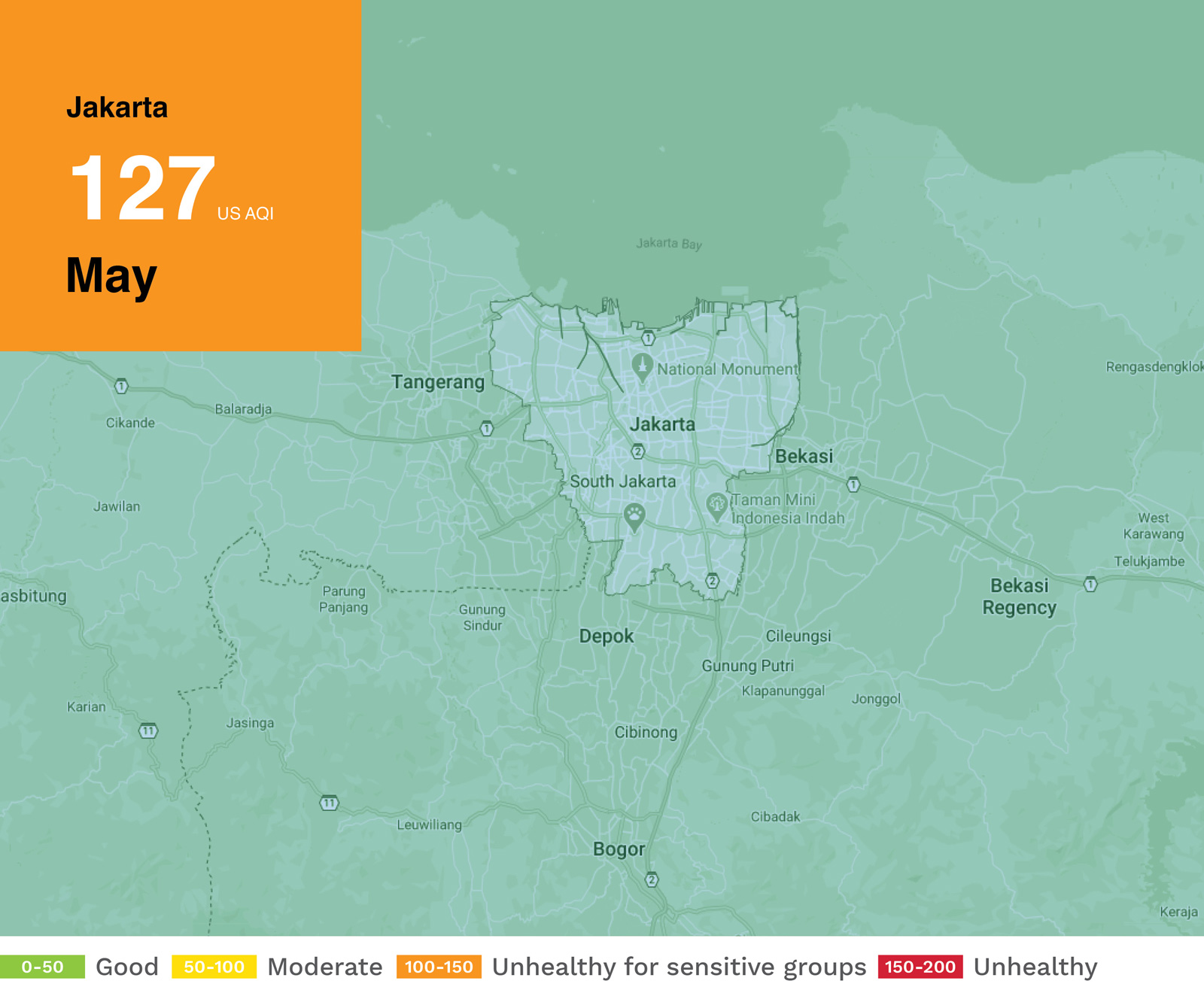

In a collaboration with the air quality specialists at IQAir, this week the Globe explored the monthly Air Quality Index (AQI) across major Southeast Asian cities recorded in the period between the February start of regional lockdowns to halt the spread of the virus and the increasing normalisation of mid-May. While the start of lockdown measures is correlated with cleaner air almost uniformly across 10 major cities in the region, there is one notable outlier – Jakarta, the mega-city Indonesian capital.

IQAir’s statistics from February shows that Jakarta measured an AQI of 82, within the moderate level of its air quality scale. While other cities bunkered down under bluer skies, Jakarta’s AQI kept rising, month-on-month, to hit the unhealthy high of 127 in mid-May.

With just over 10 million inhabitants, Jakarta is the most populous city in ASEAN and the second most populous urban area in the world, after only Tokyo. But with a stretched transport system, a new metro with only one line and a reliance on cars, the city has notoriously bad traffic and is heavily polluted. A group of residents even submitted a civil lawsuit against the Indonesian government last year because of the worsening pollution.

While snarling traffic contributes plenty to the city’s poor air quality, one of the single greatest sources of atmospheric pollution is coming from the coal-fired power plants that electrify the city nicknamed the “Big Durian”.

Jakarta is surrounded by 12 such plants within a 100km distance. One of the largest, Java 7 Unit 1, became operational in late-2019 and is over twice as powerful as all renewable energy plants launched that year.

Isabella Suarez, an analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), told the Globe that power plant emissions are “one of the many factors” driving poor air quality in Jakarta.

“The thing with air pollution is that it’s cumulative and drawn from several sources,” she explained.

Jakarta was not immune to the trend of lockdown measures introduced by governments around the world. The capital saw a significant reduction in traffic thanks to a partial city lockdown imposed 10 April and extended to 4 June, and streets often in gridlock have been notably quiet and empty during the lockdown.

While the reduction in traffic did lead to a reduction in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions from vehicles, overall air quality in the capital steadily worsened from February to mid-May.

Suarez explained that while the reduction NO2 could have in theory contributed to an improved AQI, an increase in fine particulate matter in Jakarta’s air might have offset those other improvements. That kind of matter, commonly referred to as PM2.5, refers to solid atmospheric pollutants with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometres, about 3% that of a human hair.

Suarez said PM2.5 can “have a lot of implications for how bad pollution is on a ground level”.

“[PM2.5] is formed when chemicals, such as NO2, interact with other particles in the atmosphere, breaking down further and becoming this small micro-molecule that has the potential to get deep into the human lungs,” Suarez said.

Due to their size, tiny PM2.5 particles hang for longer in the air than NO2, travel greater distances and are easily inhaled. In the IQAir monthly air quality figures, Jakarta’s monthly PM2.5 average concentration rises in March and April and continues through mid-May, worsening the AQI even while people stayed at home and fewer vehicles took to the streets.

Suarez explained that CREA’s research has found the rising PM2.5 in Jakarta during this time can be attributed to sources outside the city’s limits – that is polluting sources aside from transport, household fuel emissions, and agricultural burning, which have also contributed to some degree.

“We looked at the surrounding power plants, usually a source of PM2.5, and found that they were operating business-as-usual – the most significant of which being the Suralaya power plant, in the Banten region,” she said.

Using satellite imaging, CREA deduced that while NO2 had decreased in Jakarta, the areas over the coal fired power plants around it had no significant change.

“When we looked at the trajectory of the wind changes – in April, the wind is coming down from the south, going over the Suralaya power plant, and travelling over Jakarta,” explained Suarez. “It is a pretty clear indicator that the PM2.5 and pollution around these areas in Suralaya, made its way down to the city.”

Bondan Andriyanu, a climate and energy campaigner at Greenpeace, agreed that Jakarta’s continuous pollution, even during lockdown, is to be expected due to the nature of its energy sources.

“In Indonesia, almost 60% of our electricity comes from coal,” Andriyanu explained. “Jakarta has one of the worst qualities of air in the region, and it’s not surprising it’s the capital with the highest number of coal-fired power plants within 100km of the city.”

In 2017, Greenpeace Indonesia released a report entitled Jakarta’s Silent Killer, a look at the worsening pollution in the capital thanks to the increasing number of coal-fired power plants. Since the report’s publication, four new plants have come online near Jakarta.

“The people of Jakarta need to recognise that it is not just traffic which is damaging their health,” Didit Wicaksono, an author of Greenpeace’s report, then wrote. “The pollution from these plants is killing people now. If the new units are built, many more will suffer.”

The Indonesian government announced in January plans to remove coal-fired power plants aged 20-years or older with replacements that use renewable energy instead. But coal, which currently supplies about 60% of Indonesia’s electricity, is still expected to be the country’s dominant source of power until at least 2028.

So while the rest of the region enjoyed a much-needed respite from poor air quality, in Jakarta, not even an unprecedented global pandemic, plummeting vehicle usage and a city lockdown could mitigate the impact of the city’s reliance on coal power stations.