Shunted off Facebook, Indonesia’s extremists turn to Instagram

With more than 130 million users in Indonesia alone, Facebook has long been the platform of choice for extremists in the archipelago. But with Facebook tightening its controls over extremist content, many are turning to Instagram to promote the cause

For online extremists such as IK, it’s just not as easy as it used to be to promote jihadhist rhetoric on Facebook.

“I myself haven’t used Facebook for a long time,” said IK, an Indonesian sympathiser of Islamic State (IS) who once ran a pro-IS website. “Access to it [radical content] is already difficult, many social media platforms ban it if it is related to IS. But you can still find a lot of [IS] content on Instagram.”

Facebook, Indonesia’s most widely used social media platform with 137 million users, has made considerable efforts to crack down on certain kinds of content, claiming in 2018 it had removed 14 million pieces of terrorist content promoting Islamic State, al-Qaeda and their affiliates that year. This shift in the digital ecosystem has led IK and others like him to switch to Instagram, a lesser-used platform in the archipelago which is now offering a more open venue to his posts.

Former convicted terrorist Arif Budi Setyawan told the Globe that Instagram is now a popular medium for online extremists to spread propaganda because the platform is not as strict as Facebook in filtering content. They use certain methods so that their uploads are not flagged as dangerous.

“They [online extremists] upload photos containing narration about their teachings and propaganda sentences with good language and no visuals that show violence. Then the system will not recognise it as a dangerous upload. That’s their way of avoiding blocking,” said Arif, who is now an author at RuangObrol, an online publication aiming to counter radicalism and terrorism.

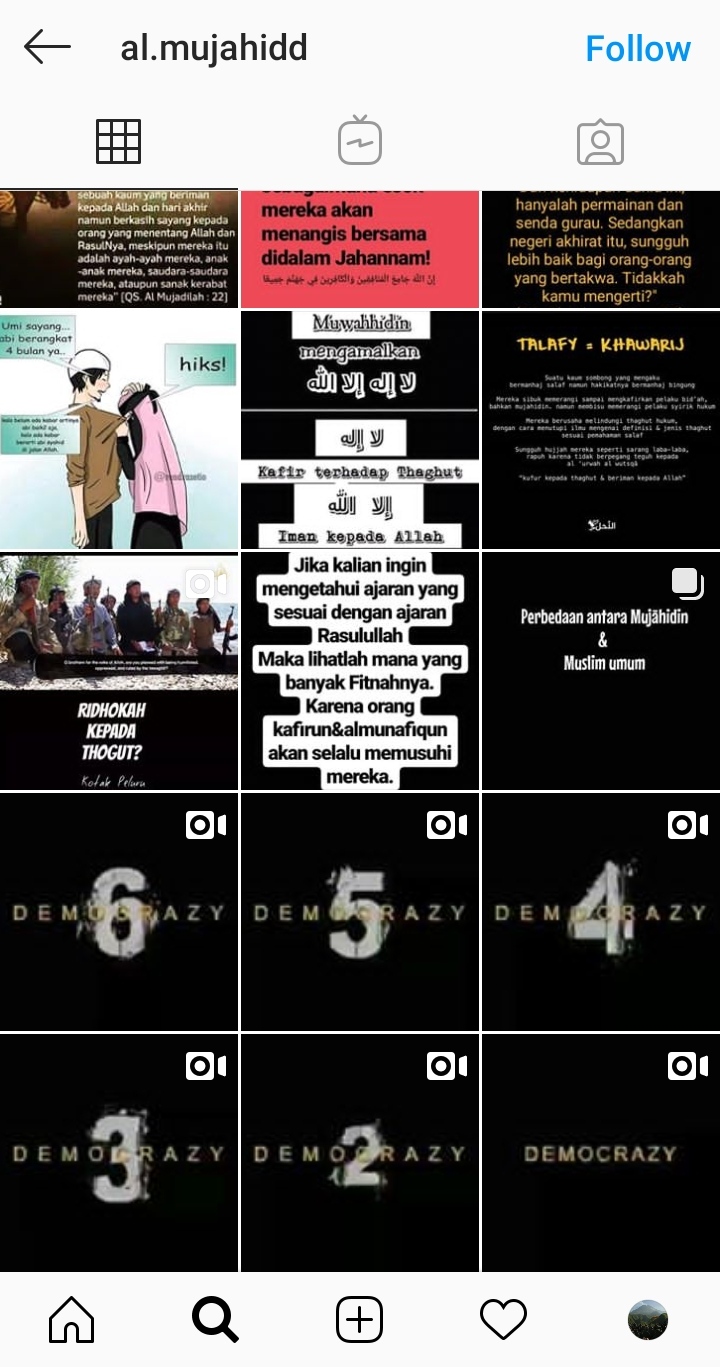

Based on IK’s testimony, the Globe browsed multiple Instagram accounts. Through handles like @dakwahtawheed, @infoakhirzaman1, @TawheedReturn, @al.mujahidd, @dakwahpengingatdiri and others, a reporter found countless pieces of radical content uploaded in recent weeks, both in the accounts themselves and within their social network. There are also several other accounts that upload strictly radical content such as @hamzahwijaya43, @abifarhan12 and @putriii_dzlt.

Online extremists share content with each other and are connected through Instagram’s follower and following features. Much of the content uploaded is built around Indonesian radical cleric and IS recruiter Aman Abdurrahman, as well as the teachings of Tawheed – referring to an Islamic concept of oneness with Allah.

Like many jihadists, prior to his arrest Abdurrahman went by multiple names, including Oman Rohman and Abu Sulaiman. The fluid identity wasn’t enough to cover his tracks though, and the cleric was sentenced to death in 2018, charged with inciting his followers to carry out at least five terror attacks in Indonesia. Although Aman Abdurrahman is currently in a high-security prison on Nusakambangan Island, his lectures are still widely circulated online.

Data from the Indonesian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kominfo) shows that content blocked on Instagram and Facebook spiked from eight instances during the 2009-2017 period, to 7,160 pieces of extremist content in 2018 alone. Extremist content removed from Twitter (1,316), Youtube (677), and Telegram (502) paled in comparison.

The spike occurred after Kominfo used a crawling artificial intelligence machine to detect offending content. The agency provides facilities to report the content, including through their website and Twitter.

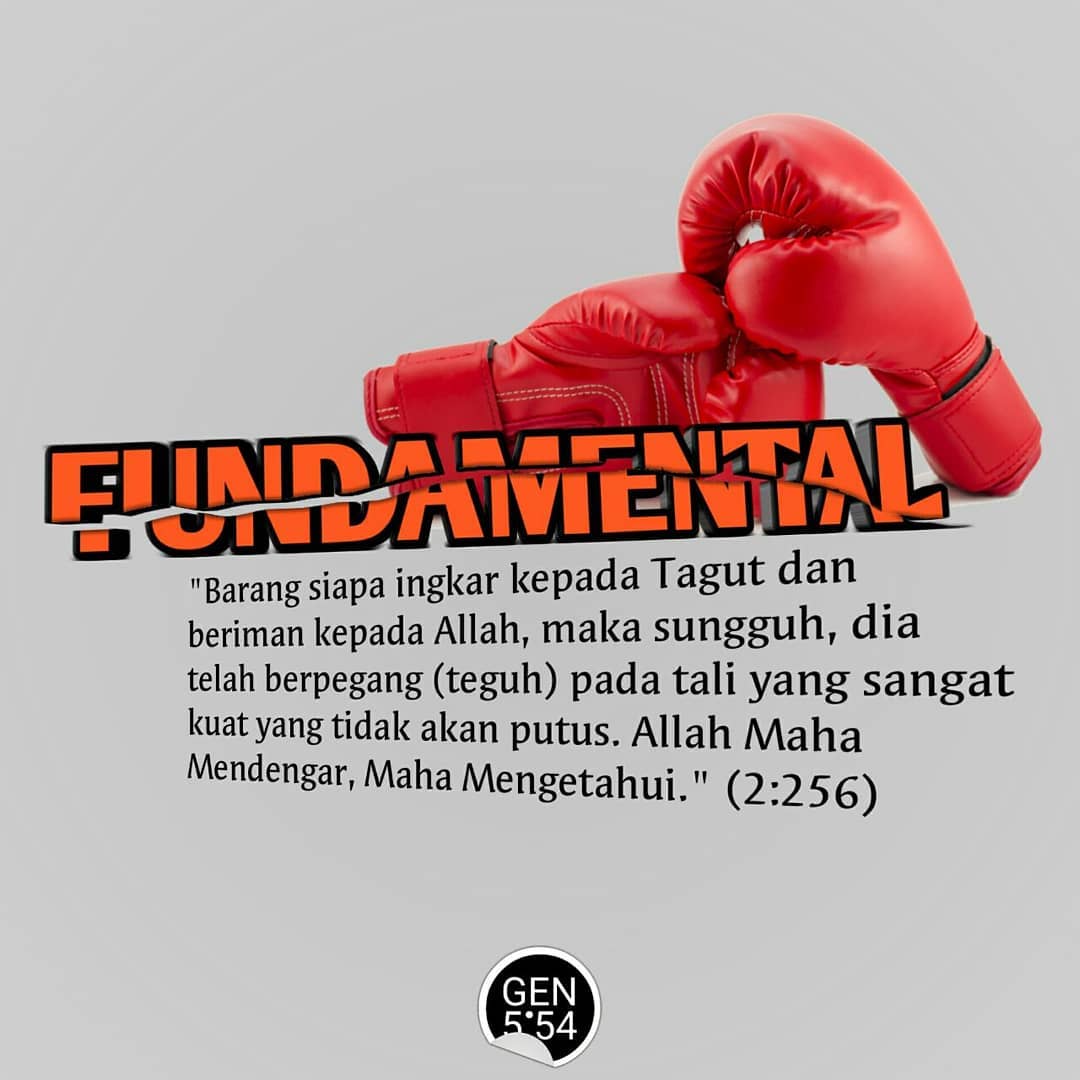

According to Indonesia and the Tech Giants vs ISIS Supporters: Combating Violent Extremism Online – a July 2018 report by the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict – the Saveme Project and Gen 5.54 are two major producers of radical content in Indonesia. Social media platforms have made strides in stifling Gen 5.54’s content, a platform that emerged in October 2017.

“Gen 5.54 was much more creative and technologically skilled. Telegram, however, banned Gen 5.54 groups in May 2018 and its Android app became inaccessible around the same time,” the report stated.

The Saveme Project also had their accounts on Instagram, YouTube and Telegram blocked around 2018, but the legacy of their content is harder to squash.

The @al.mujahidd account, for example, uploaded several short videos in June 2019 made by Saveme Project containing a recording of an Aman Abdurrahman lecture. Another post shows a video of a jihadist from Indonesia, Abu Muhammad al Indonesi a.k.a Bahrumsyah, calling on Muslims to leave for jihad in Syria. The video, first released in 2014, was re-uploaded to the account on June 9, 2019.

An online extremist using the pseudonym Lebah Muda told the Globe via Telegram that it is no longer a surprise for online jihadist that their accounts are suspended for posting IS-related content on digital platforms like Facebook.

Some of his friends are members of a radicalist WhatsApp group called Sayap Merah (Red Wings), where IS sympathisers exchange radical content in the form of videos, pictures, notes and MP3s, posting them on Facebook and Instagram. He said members of the group often complain about their accounts being suspended and their content blocked since Facebook implemented tighter security standards towards the end of 2019.

Confirming this, in mid-October a reporter attempted to access pages, accounts, groups and posts on Facebook related to IS and terrorism with no success. This stands in contrast to last year, when radical content was easily accessed by typing in keywords Tawheed, ghuroba, and thaghut.

But this lack of hits could be in part the result of extremists becoming more savvy and censorship-conscious. Muda said he now chose the “safe way” to spread his beliefs on Facebook by no longer uploading content related to IS, but instead posting content related to the teaching of Tawheed.

The lowest level of loyalty for them is to spread content … Then the next level is funding terrorism-related activities, and the highest level is carrying out acts of terrorism

“This is a way to make my account last long. My account has been suspended by [Facebook] several times. But thanks [to] God, my latest account is still active for almost two years,” he said.

The Globe checked Lebah Muda’s Facebook account and found several posts related to radical teachings posted in recent weeks. On October 10, Muda uploaded a video related to IS propaganda, before a day later uploading a video containing a voice recording of Aman Abdurrahman.

A Facebook representative for Indonesia and Timor-Leste was not immediately available for comment.

Terrorist-turned-reformist Arif said the dispersed nature and lack of coordination among online extremists in Indonesia made it difficult to identify who they are. He added that many view the spread of online content as the minimum requirement for furthering the cause.

“The lowest level of loyalty for them is to spread content,” the 36-year-old said. “Then the next level is funding terrorism-related activities, and the highest level is carrying out acts of terrorism.”

Arif encourages people to actively report on accounts spreading radical teachings and propaganda, along with government and platform providers to monitor and take down these accounts and content.

“All parties have a role to play in overcoming the spread of radical content on the internet,” he said. “Online extremists are always looking for ways to spread their propaganda, so don’t be careless.”