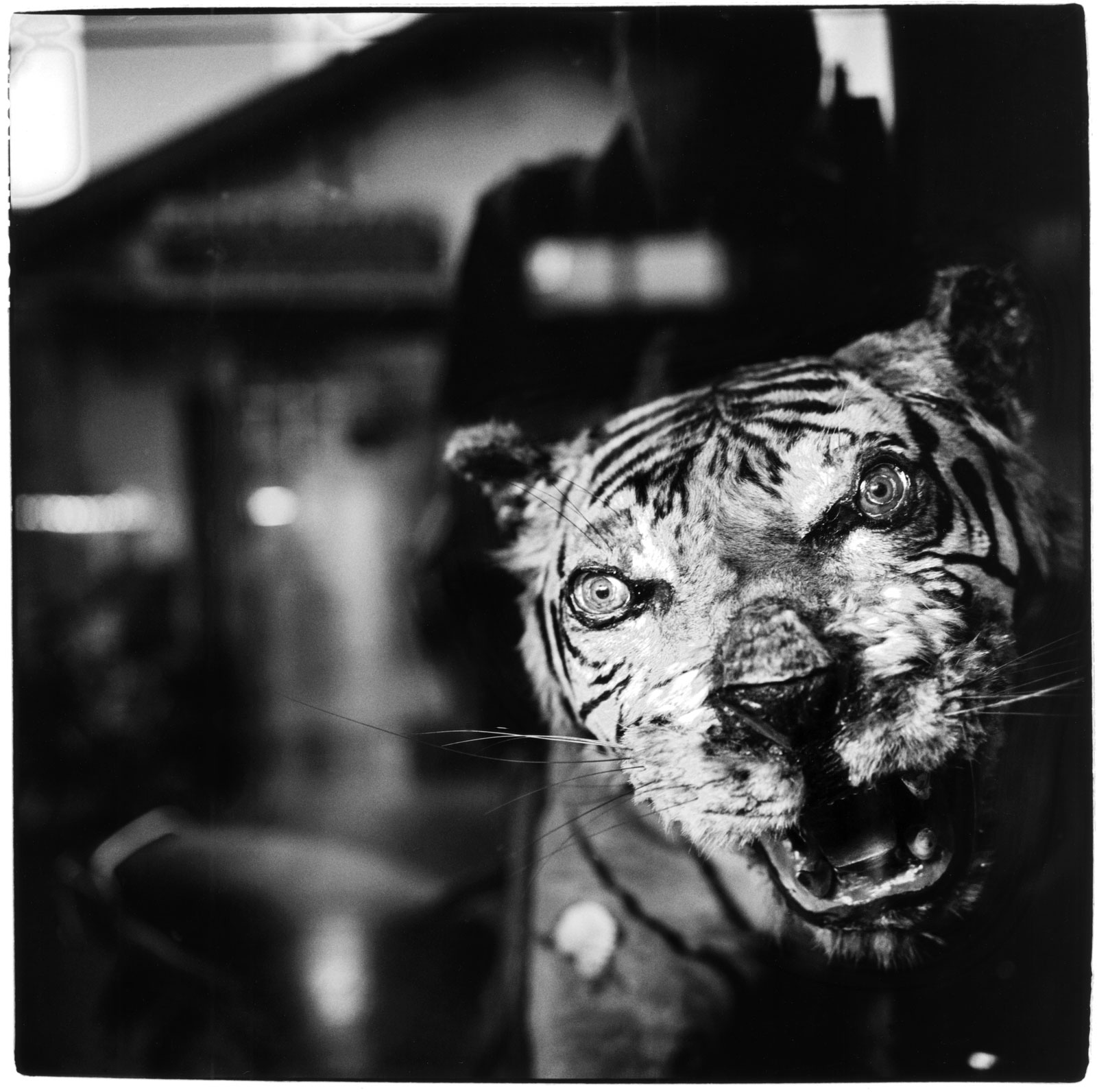

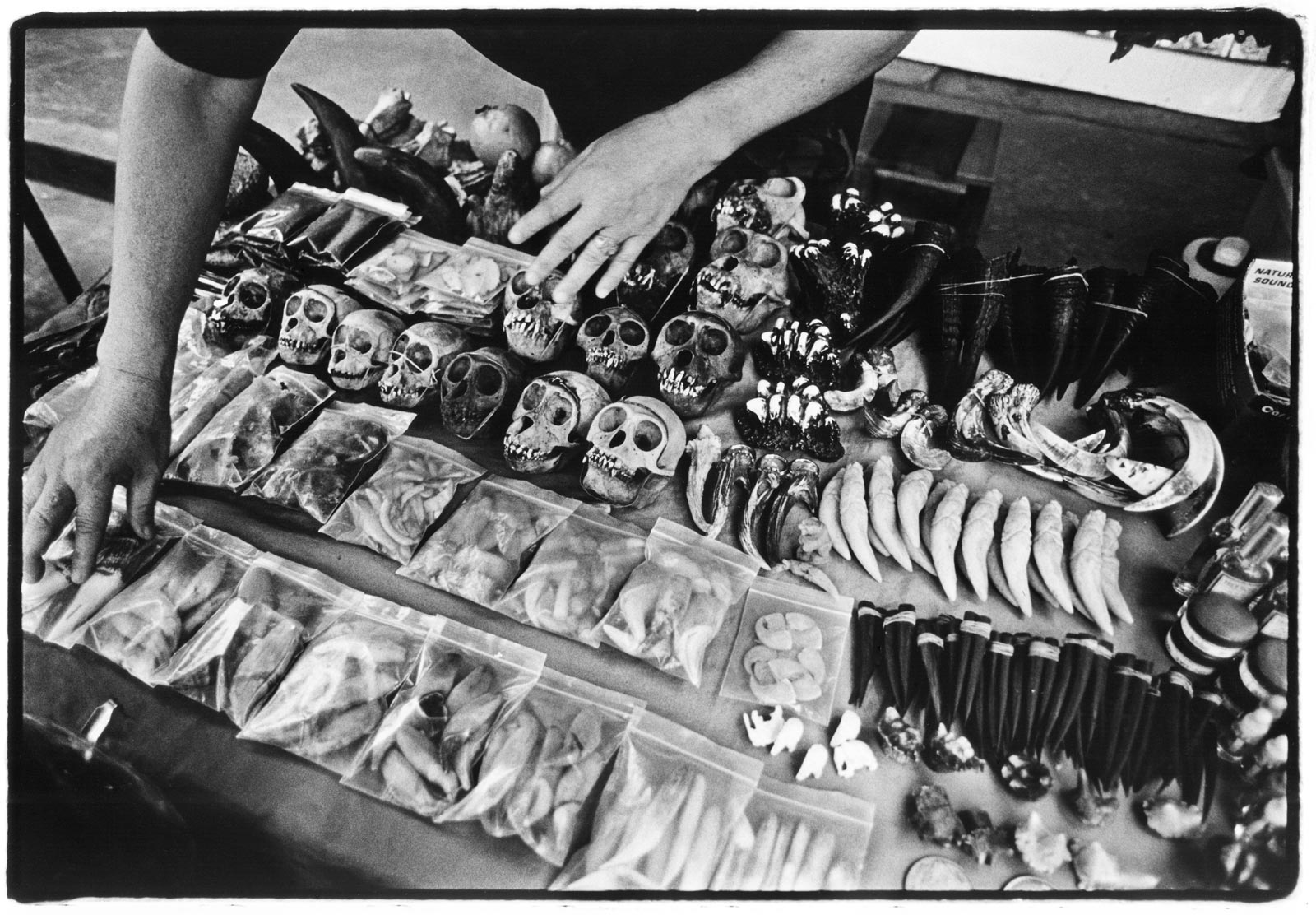

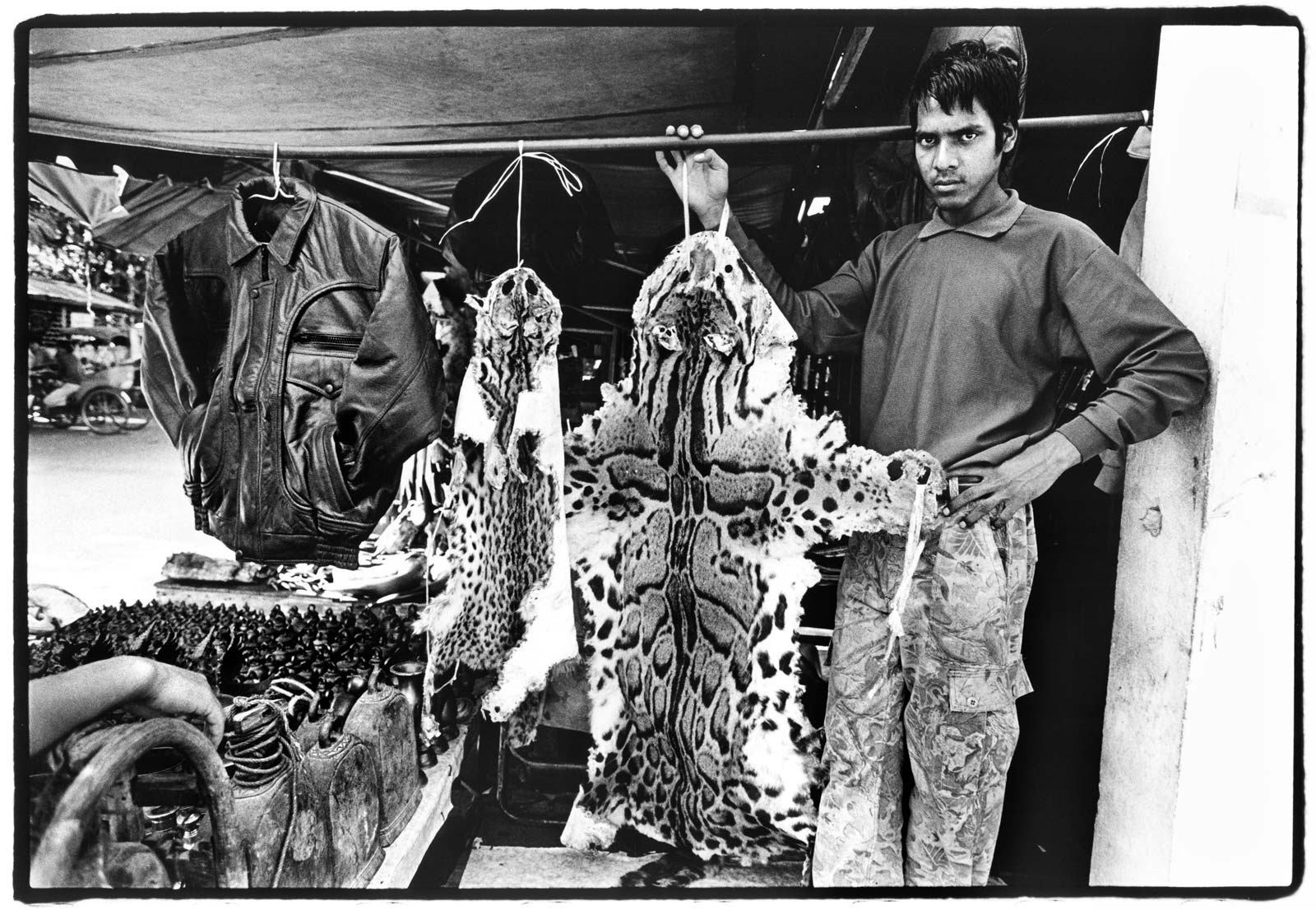

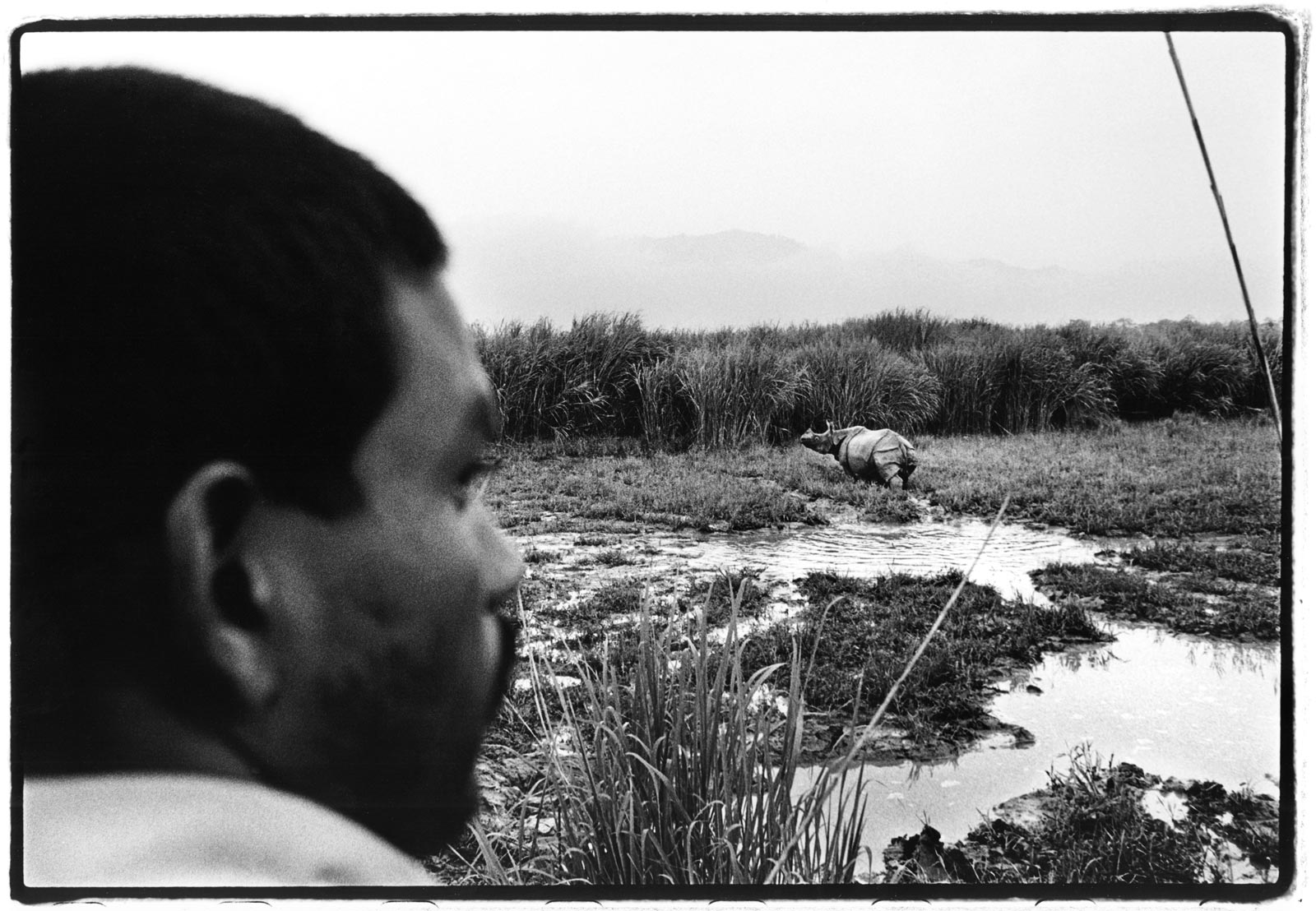

Editor’s note: In November 2008, Southeast Asia Globe published these extracts from “Black Market – Inside the Endangered Species Trade in Asia” by Ben Davies. Illustrated through haunting photos by Patrick Brown, the book follows the world’s illegal wildlife trade from the jungles of Assam to the brothels of Saigon. Despite decades of fighting back against poachers and the wealthy officials who turn a blind eye, endangered wildlife trafficking remains rampant across Southeast Asia, driven by rising demand for animal parts for trinkets, talismans or traditional medicine.

On a cliff overlooking the southwest plains of Cambodia, there is a bullet-ridden casino. Built in the 1920s, when Bokor was a hill resort largely reserved for wealthy French colonials, during the 1970s and 1980s it became the front line in the battle between the Khmer Rouge and government forces. These days, a different war is going on.

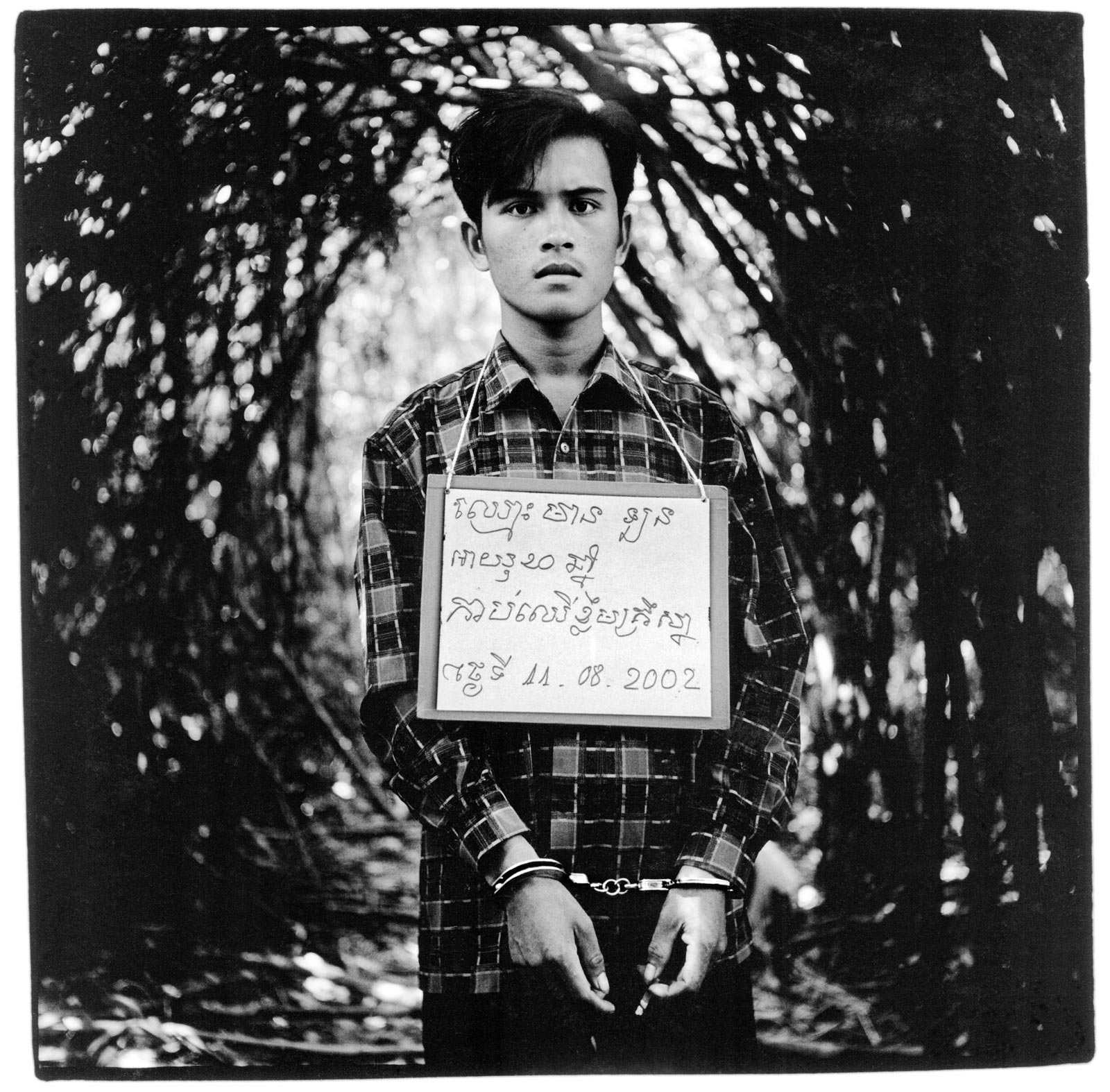

Six heavily armed men make their way through the forest using only the light of the moon. Carrying automatic weapons they tread carefully. Up ahead they see a movement. One man signals and the others melt on either side of the track taking up ambush positions. Ek Phirun, the head of the unit, shouts a command and a spotlight blazes, freezing the figure of a poacher. Surrounded and outgunned, the man surrenders without a struggle. This time the catch is small: a hog badger that will sell for less than $20. But like so many species in Cambodia, it is endangered – and its price tag could increase many times when it is transported further afield.

The poacher is taken away for questioning and later released. An off-duty soldier, he was foraging for animals to feed his family.

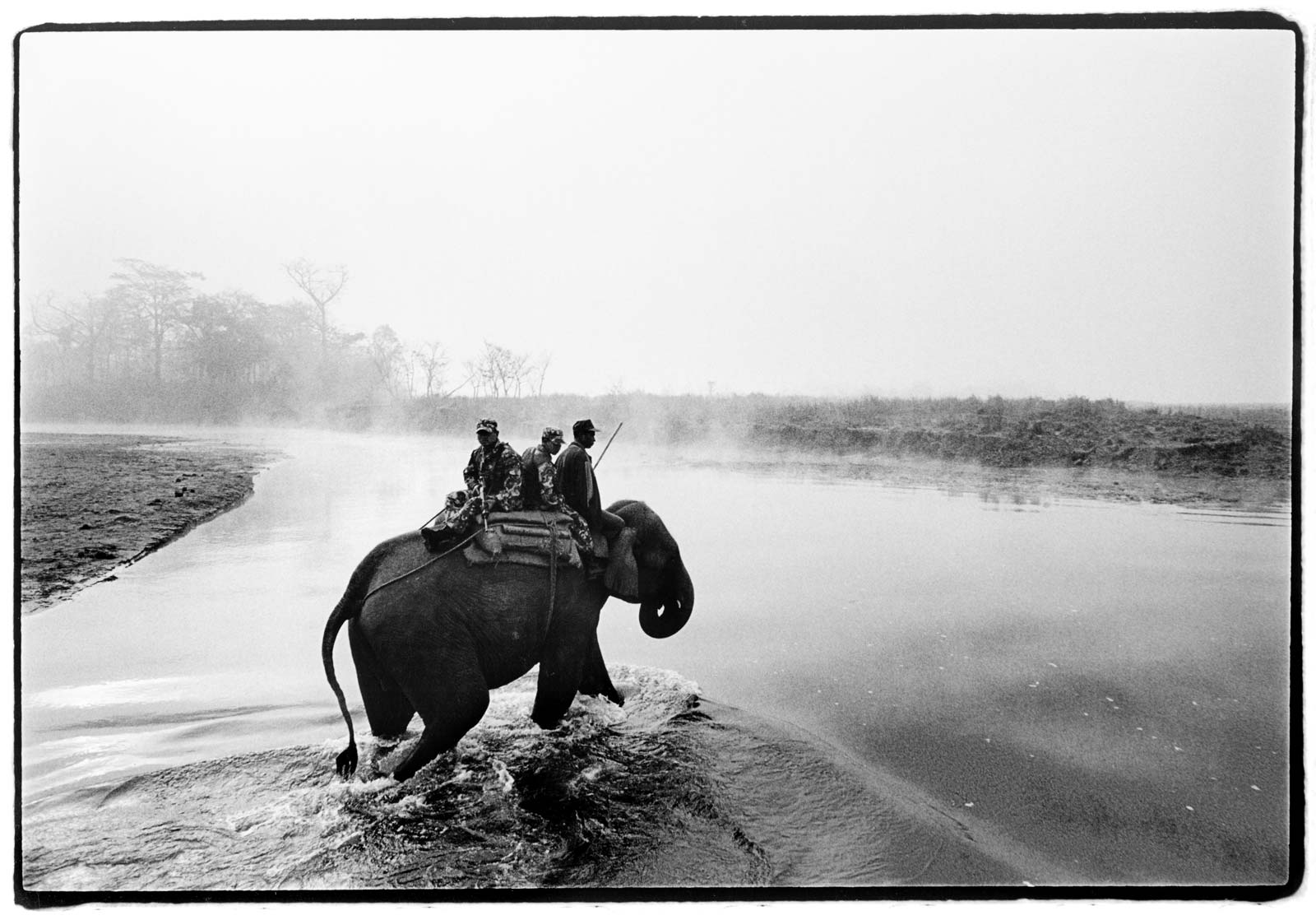

The wildlife patrol is there to guard one of the last refuges for several of the world’s most endangered species. It’s dangerous work. They have been fired upon and held at gunpoint. In one incident, several men received shrapnel wounds when a grenade was thrown at them from the jungle. These are Cambodia’s unsung heroes, whose efforts go largely unreported.

Stringing up hammocks between the trees, the rangers sleep under the stars. The following morning they return to base in the village of Prich Nhil. “We can’t stop the illegal wildlife trade, but we can make it more difficult,” says Mark Bowman, a burly, 6’2” Australian military adviser for Wildlife Alliance (formerly WildAid), a conservation organisation that is helping to fund and train the rangers in a bid to save Southeast Asia’s wildlife.

Here in the remote national parks and forests everything has value. From the yellow vine that sells for a few dollars per kilo to snakes, wild pigs and even the innocuous centipede. It’s the prospect of big money, however, that is attracting the organised gangs of poachers who kill rare animals to supply the international black market.

Like the illegal trade in drugs, it is demand from unscrupulous buyers that fuels this grisly trade. When the killing is over, the most valuable animals are taken to dealers who sell them to traders in Phnom Penh. From there the illegal booty will be smuggled to neighbouring countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. The bones will be used for traditional Chinese medicine, the meat will be eaten as a tonic, an aphrodisiac or an expensive local delicacy, while the skins will be sent as trophies to wealthy collectors.

In the past five years Sun Hean, deputy head of the forestry protection department, believes that 200 tigers have been killed, representing as much as 50% of the country’s population. Now tigers and elephants are so rare even the elite hunters are finding it hard to locate them.

Cambodia is one of many countries whose wildlife is up for grabs thanks to the endemic poverty of its people and the insatiable greed of rich consumers. Many of Asia’s last virgin forests and wildlife strongholds are being plundered to supply the illegal trade – estimated by Interpol to be worth at least $6 billion a year.

Every 30 seconds a plane takes off or lands at London Heathrow, the world’s busiest international airport. On a warm July morning Charles Mackay, head of the wildlife customs unit for Her Majesty’s Government, is called to inspect a shipment en route to South Korea.

Inside a wooden crate he discovers ten rare, African dwarf crocodiles, a dozen royal pythons and a large collection of monitor lizards. Documents accompanying the shipment claim the reptiles are legitimate exports bred on a farm in Benin. Vigilant customs officers, though, recognise that the documents are fake and confiscate the consignment. Their mouths taped and their bodies bent double inside sacks, the big surprise is that the animals are alive.

Never before has it been so easy to trade in wild animals. Every year at least 25,000 primates, 2m to 3m birds, 10m reptile skins and more than 500m tropical fish are bought and sold around the world – and that’s the legal trade. Driving this seemingly endless appetite for rare and exotic species is a bizarre new phenomenon. Gone are the days when it was fashionable to have a chihuahua or hamster as a pet, now people want birds and snakes that are exotic to look at and easy to keep.

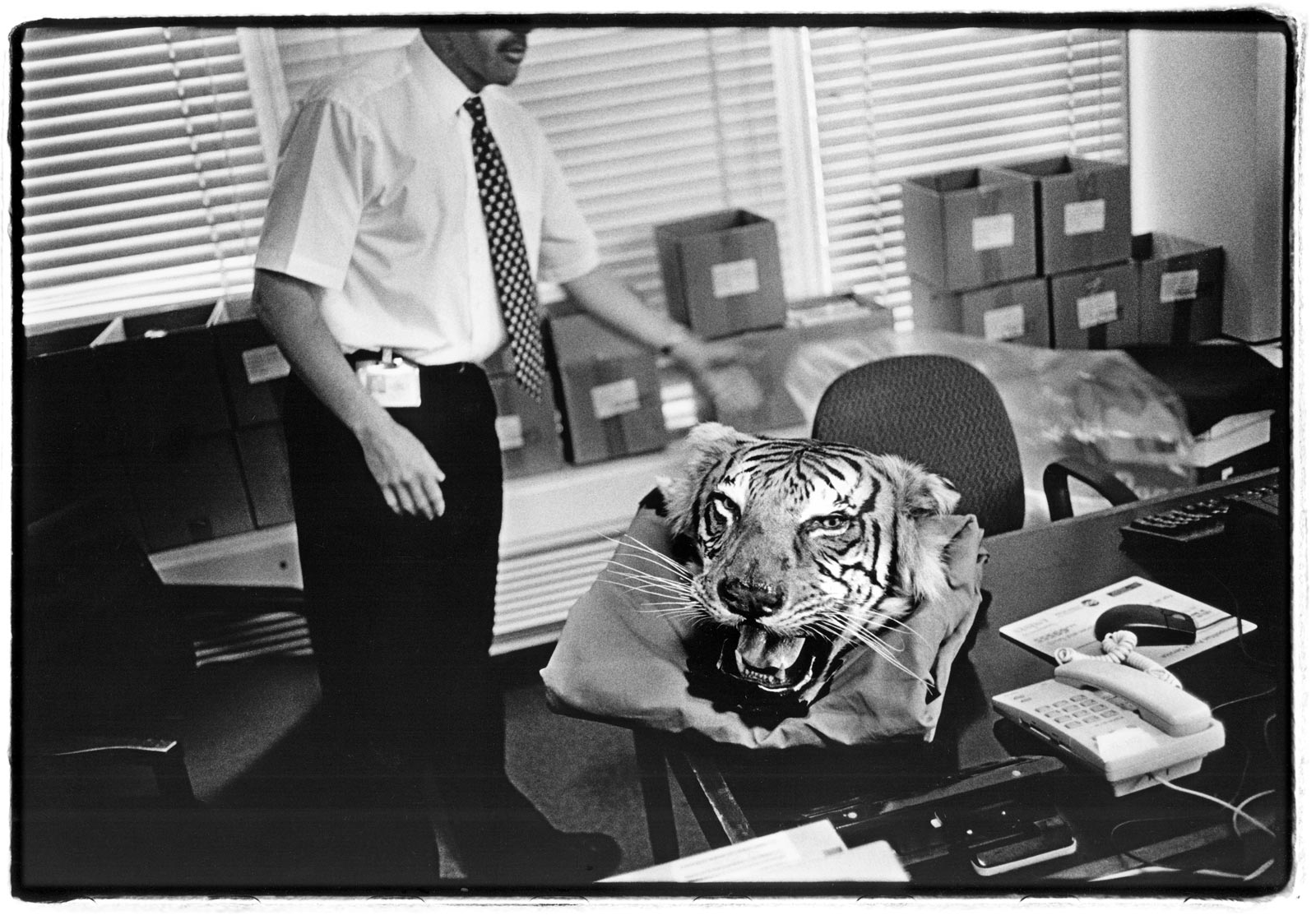

It’s a one-hour drive from Heathrow to the 19-storey, glass-fronted headquarters of London’s Metropolitan police. New Scotland Yard is where the enforcement unit charged with monitoring wildlife crimes is based. Despite its grandiose-sounding name, the resources allocated to the wildlife crimes unit are pitiful. While the Met employs 40,000 officers in total, it allocates only two full-time officers to wildlife.

“The wildlife trade is not a priority,” admits Andy Fisher, who heads up the department and has been instrumental in efforts to raise awareness about the illicit trade. “Fighting class-A drugs, theft and anti-social behaviour is where the Met concentrates its resources.”

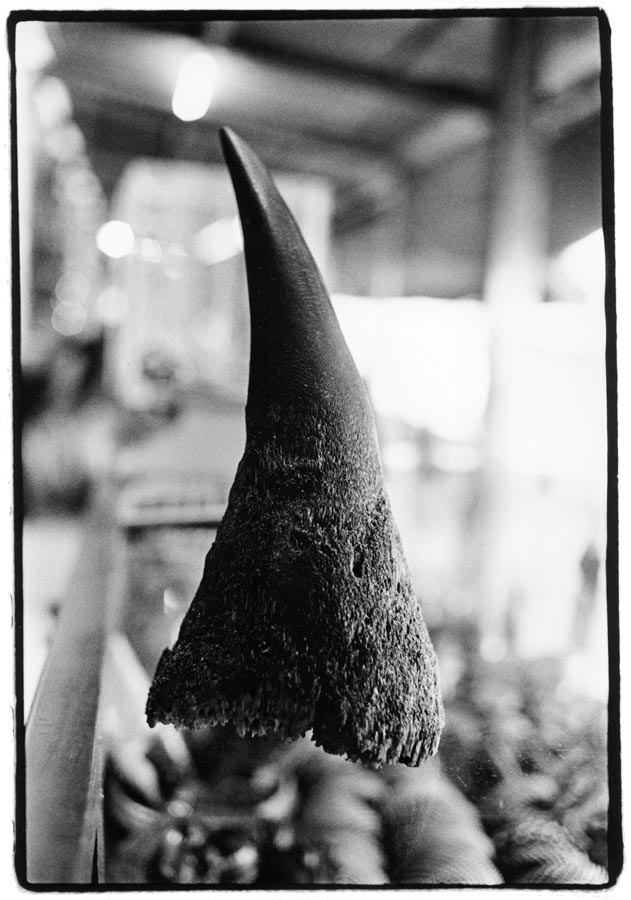

In his second-floor office, Fisher has a collection of animals and animal parts that any rogue dealer would be proud of. Thrusting his hands into a cupboard he brings out a mounted, ten-day-old tiger cub worth about $6,000 that officers seized from a north London taxidermist shop named Get Stuffed. He also has shawls made of fleece from the endangered Tibetan antelope that sell for as much as $17,000 each. Added to that are dozens of remedies containing tiger bone, bear gall bladder and powdered rhino horn, confiscated from some of the hundreds of traditional Chinese medicine shops around the capital.

To avoid the stringent searches carried out in British ports, big wildlife shipments are sent through Holland, Belgium, Spain and Germany. Once inside the European Union, illegal shipments can be moved across borders as easily as a truckload of vegetables. The failure of comparatively well-to-do western nations to stop the illegal trade in wildlife has encouraged open slaughter of animals in the developing nations of Asia and elsewhere across the globe.

Fortunately, where there are criminals there are also heroes; men such as Sawaek Pinsinchai, the 58-year-old police major general who was appointed head of the Thai forestry police. “I am not frightened of taking on wildlife traffickers,” he says. “We are using the law and I have the support of the prime minister, the public and the queen of Thailand.”

In the days and weeks that followed, Sawaek’s investigations revealed that an illegal slaughterhouse he had raided was part of a ruthless blackmarket ring that also sent live animals over the border to Laos, Vietnam and China. The operation had flourished as a result of high-level protection. “This was one of the biggest and most powerful syndicates in Thailand,” he says. “From politicians to high-ranking officials and police, many people were involved.”

In a second raid conducted less than a week later, a team of more than 300 police and forestry officials descended on Chatuchak, Bangkok’s weekend market, seizing more than 1,000 protected species valued at about $1.2m and arresting several people. Among the confiscations were rare turtles, snakes, slow lorises and hornbills stolen from the country’s protected national parks.

The following day a third raid was made on a house in the Pracha Cheun area of Bangkok. Nearly 100 protected birds as well as a collection of civets and pythons were seized along with a frozen baby orang utan. Investigators believe the orang utan was shipped from Sumatra or Borneo where it still occurs in the wild, although in rapidly declining numbers.

The most shocking thing was that this level of smuggling could take place in Thailand, a country which is a signatory of the convention on international trade in endangered species of wild flora and fauna (CITES), an agreement signed by more than 160 nations around the world.

The jury is still out on whether the raids mark a turning point in the Thai government’s attempts to stop the trade or are merely another public relations exercise.

Money oils the wheels of the illegal wildlife trade. A baby orang utan taken captive in the rainforests of Kalimantan in Indonesia maybe worth $200. By the time it reaches the capital, Jakarta, it will sell for $2,000. The big money, however, is made exporting and trafficking the animals. Smuggled into the West, the same orang utan could net a trader 20 times as much.

China is the number one destination for illegal wildlife. It is the world’s largest consumer of ivory importing as much as 15 tons each year, the equivalent of 1,500 dead elephants. It swallows more than half the 10,000 tons of freshwater turtles traded annually in the region. It is the biggest market for tiger bone, rhino horn and sea horse – still widely used in traditional medicine. As an old Chinese proverb says, the nation consumes everything with “its back to the sky”.

The magnitude of the problem is staggering. “China is like a vacuum cleaner,” says James Compton at TRAFFIC, an organisation that monitors the illegal trade in the region. “It is the single greatest threat to wildlife in Asia.”

While it is easy to point the finger at China, there are plenty of other culprits. The US is the biggest buyer of exotic pets in the world; nearly 7m households own a bird and a further 4m own a snake, turtle or iguana. Japan is a big buyer of ivory.

In a small, crowded shop in the Tsukiji district near Tokyo’s fish market, the scale and international reach of the trade is hard to ignore. Surrounded by mounted deer heads, giant turtle shells and piles of ginseng, a stuffed polar bear wrapped in polyethylene is on sale for $11,000. Stuffed tigers, black pumas and leopards are also up for grabs. For $408,000 the shop will even sell a stuffed giant panda over the internet.

Asked about the blatant display and sale of endangered species Mr Itoi, the owner, says he has no problems with the police. “Buying one or two items will not hurt at all,” he says. “There is no way you will be in trouble.”

The same however is not true of the giant panda. Recently seven people in China were executed for attempting to export the national animal. “I cannot display it here,” says Itoi. “You can get killed for that.”

Every two years a gathering of more than 1,000 conservationists and government officials takes place in one of the world’s major cities. Known as the conference of the parties to CITES, this is the single most important event on the international conservation circuit. Inside vast meeting rooms, delegates from 164 countries decide what animal and plant species are threatened by the trade and which should be subject either to quotas or a ban on international trade.

To date, CITES has banned the commercial trade in tigers, rhinos and 220 other species of mammals. It has also provided varying degrees of protection to more than 30,000 species of animals and plants. There is just one problem. Like any convention or set of rules it is only as good as its implementation, and its resolutions have been flouted, circumvented or ignored with impunity.

Thousands of miles away from CITES’ air-conditioned offices in the remote town of Mongla in Myanmar, a young Akha trader deals openly in animal parts. Clutching a shoulder bag with pink, blue and red tassels, he saunters from shop to shop in the cool of the late afternoon, negotiating prices with the various owners. Asked what is in his shoulder bag he rummages among the contents and produces something that resembles a piece of ginger root; it is in fact a tiger’s dried penis. He also has two tiger kneecaps with the texture of polished marble and the weight of pumice stone.

The man has come from a village in the remote hills, a two-day journey from Mongla. He bought the tiger parts from another hunter to sell them to one of the many shops dealing in wildlife. “The kneecaps cure arthritis, the penis makes you strong,” he says. The price for these rare items – $80.

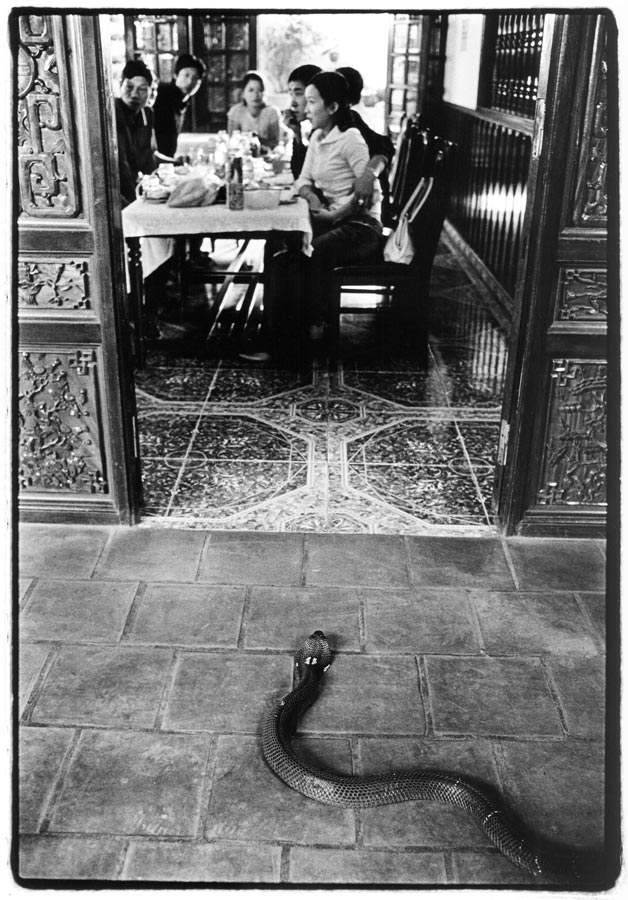

Situated in the northern hinterlands of Myanmar, Mongla is a town built on heroin money. Made up of gaudy casinos, brothels and five-star hotels it is a beacon of wealth and prosperity surrounded by a sea of poverty and oppression. In its wildlife market, surrounded by open-air restaurants, a dozen or so rusting wire cages are stacked on trailers.

The cages contain a variety of exotic animals, their eyes peering out in horror as groups of would-be diners poke them with wooden sticks to see how much meat they have. On one trailer is a rare hornbill, its gigantic yellow beak poking out of a wicker basket; on another is a tawny eagle, its wings folded uselessly by its side.

In the most pitiful condition of all is a macaque that insanely rattles the bars of its cage, driven by the pain of having its left leg torn off by the steel jaws of a trap.

For the bored wildlife vendor from Yunnan province in neighbouring China, the catch is hardly anything out of the ordinary. “We sell whatever the hunters find in the forests,” he says, pointing at the cowering animals living out their last hours cooped up in wire cages. “Come back later. If you are lucky we may have a bear or a tiger.” Today the vendor is out of luck and the hunters have nothing more to offer.

By nightfall the wildlife is all gone, the macaque taken to a nearby restaurant where its skull will be sliced open while it is still alive and its brain eaten by men with chopsticks who believe the meal will improve their intelligence. Gone too is the hornbill. Only a small eagle remains, although it too is later bought by a group of Chinese tourists who plan to eat its eyes because they believe this will improve their eyesight.

The sheer volume of killing makes a mockery of attempts to stem the trade in endangered wildlife species. Ruled by a military junta and patrolled by soldiers carrying semiautomatic weapons, Mongla was until the late 1980s simply another narco-state.

But in June 1989 the generals in the Myanmar capital of Rangoon cut a deal with Lin Mingxian, the area’s kingpin, creating special region 4 and granting the region virtual autonomy. The agreement has enabled the local militias to pursue their illicit activities unhindered while allowing the government to disclaim all responsibility.