The works of Indonesia’s writers are barely known in the literary salons of New York and London, but moves across the archipelago could help a talented new stable of authors ink their names on the bestseller lists

By Nithin Coca

At most literary soirées, mentioning the works of Okky Madasari, Ayu Utami or Seno Gumira Ajidarma would result in a round of blank stares. But drop those names at a book club in Jakarta, Surabaya or Yogyakarta and you will earn approving nods from the assembled bookworms. All of them are award-winning, bestselling writers in Indonesia – one of the world’s fastest growing literary markets – yet they are barely known abroad.

“What is truly amazing about modern Indonesian literature is its vibrancy,” said John H. McGlynn, chairman and co-founder of the Lontar Foundation, a Jakarta-based NGO that promotes Indonesian literature. “This is especially evident in the versatility of Indonesian writers who, from colonial times to the present, have maintained a consistent ability to cross literary genres.”

For centuries the country, located along important trade routes connecting the cultural hotspots of China, India and mainland Southeast Asia, has itself been a centre for arts and culture. Indonesia boasts a proud literary tradition in numerous languages, most notably Javanese and Malay, dating as far back as the 15th Century.

Today the country is undergoing a book boom. Since the fall of former dictator Suharto in 1998, and the subsequent relaxation of most censorship and freedom-of-expression restrictions, Indonesia’s literary output has grown from about 6,000 titles a year to more than 30,000 in 2013, according to the Indonesian Publishers Association.

“Since 1999, after the draconian government-issued publishing permit system was scrapped, people were publishing left, right and centre: fiction, non-fiction, religious, experimental, you name it,” said Indonesian author Laksmi Pamuntjak, whose novel Amba has just been published in English as The Question of Red. “There was a new thirst for alternative readings, not just of the Suharto regime’s myriad misdeeds, but also of the anti-communist massacres of 1965-1966.”

Despite their domestic popularity, Indonesian titles are not breaking out and topping book charts elsewhere. Nearly all works are written in Bahasa Indonesia, the national language that is based on Malay, and very few titles are being translated into English. The Lontar Foundation, established in 1987, whose primary aim is to promote Indonesian literature and culture through the translation of the country’s literary works, estimated that in 2013, only 24 titles were translated into English. Of those 24, Lontar was responsible for 21. This means that more than 99% of Indonesian literature, including most bestsellers and even classical masterpieces, is inaccessible to a global audience.

But translation is an expensive undertaking and profit margins are notoriously tight. According to Lontar it costs IDR150,000 ($13) per page, meaning a 400-page book would cost $5,200 to be translated into English.

McGlynn believes the government could play a greater role in supporting translations. “In fact, publishers are open [to Indonesian authors] as long as they don’t get killed [financially] in the process,” he said. “They won’t take up the costs of translation on their own, however.”

Countries such as South Korea, Turkey and Argentina have set up government-funded literary institutes that allow global publishers to not only reduce the costs of translations, but to also better identify authors and titles that may appeal to the global market.

“It would be good to see more publishers in other countries finding and translating Indonesian literature,” Kate Griffin, international programme director at the British Centre for Literary Translation, told Al Jazeera. “But many UK publishers, although curious about Indonesia, would not necessarily know where to find information about Indonesian writers.”

History and geography also play their role, according to Pamuntjak: “The lack of an Indonesian diaspora and good literary translators, as well as the fact that the country has very little shared history with the traditional world centres of publishing – the US and UK – certainly contribute to the problem.”

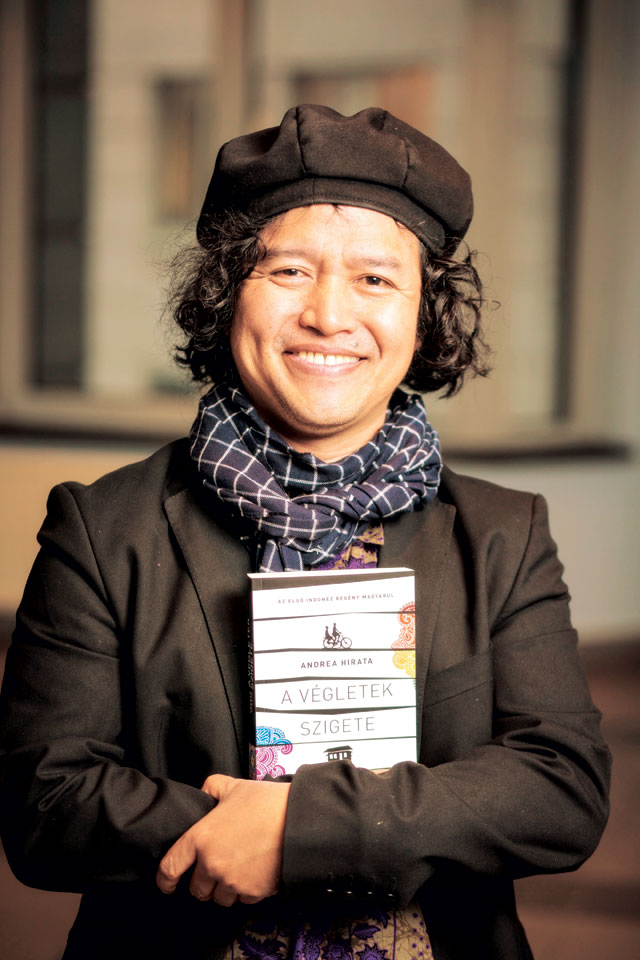

on Belitung, just off Sumatra. Photo: Kállai Márton

Change may be on the horizon, however, with Indonesia gearing up for a unique global opportunity. In 2015, the country will be the guest of honour at the Frankfurt International Book Festival, the world’s largest book fair. In preparation, Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture initiated a programme late last year to prepare 150 translations in both English and German for the festival. Advocates hope this will turn into a full-scale government literary agency.

“The fair is a wonderful opportunity to raise the profile of Indonesian literature in Germany and in other international markets,” said Griffin.

McGlynn feels that Indonesia’s preparations for Frankfurt have changed how local publishers are approaching the global market, which is a big step in the right direction. “Up until now, Indonesia had a presence at the fair, but it was just buying rights – a one-way relationship,” he said. “Starting this year, there will be 40 Indonesian publishers there, aiming to sell rights abroad.”

As new opportunities emerge, aspiring Indonesian writers also have a model to look up to. Andrea Hirata’s 2005 book Laksar Pelangi (The Rainbow Troops) is one of the few contemporary Indonesian books to break through globally. This heartwarming story of a group of poor students and their two inspirational teachers at a school on the island of Belitung is currently available in 19 languages.

Hirata is optimistic that his success will open the door to others. “There are so many talented Indonesian writers and the number of books published each year has significantly grown,” he said. “Indonesia also has more and more translators who can get works across cultural barriers.”

The quality of output is increasing too, as the dramatic changes that have taken place in Indonesia over the past decade have paved the way for ambitious, new writers.

“Today, major mainstream publishers have no qualms about – publishing ‘daring’ works, both in content and style, and this is a very encouraging development,” said Pamuntjak. “We have some wonderful authors with distinctive voices,” she added, naming Oka Rusmini and Eka Kurniawan as good examples.

If all goes well, and if Indonesia’s government can build on Frankfurt, perhaps these names will be on everyone’s lips at global literary events for years to come.

Keep reading:

“Fixing a hole” – From heroin-addicted sex worker to best-selling author, Kate Holden tells Southeast Asia Globe about fighting social misconceptions and the literary world’s double standards