This article is part two in our deep-dive into Southeast Asia’s modern-day pirate problem. You can read the first part here. Feature photo: Eric Pasquier

On June 11, 2015, a team of eight nervous pirates boarded the MT Orkim Harmony, a Malaysian tanker carrying 6,000 metric tonnes of petrol worth over $5 million. Wielding pistols and parang machetes, the Indonesians held the ship’s 22 crew members hostage, switched off the vessel’s tracking system, and hurriedly dripped paint over the side of the ship, blacking out a handful of letters to make its name less identifiable.

The freshly dubbed “Kim Harmon” chugged toward the Gulf of Thailand, off the grid for nearly a week before being discovered in Cambodian waters on June 17. The pirates had not, by that time, managed to siphon off the ship’s cargo.

Their inaction meant that, when discovered, the authorities were able to recover the ship’s crew and cargo completely intact – which they did within days. By June 19, all pirates had been arrested and the ship’s crew safely returned home. Even better, within three months, headlines shouted the news that the “mastermind” behind the hijacking – a man named Albert Yohanes – had been found and apprehended in Indonesia.

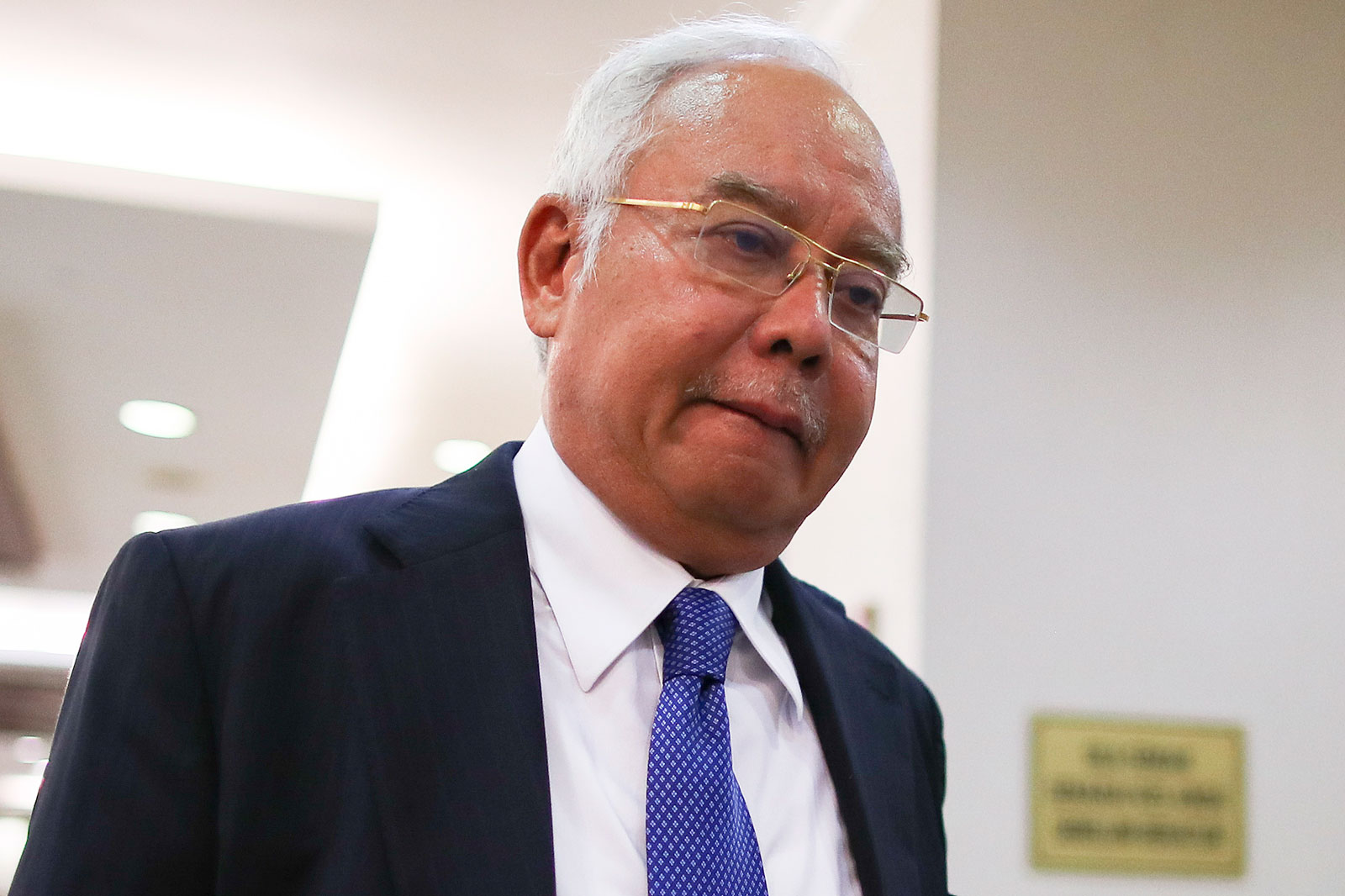

At a forum in mid-2016, Najib Razak, then the prime minister of Malaysia, lauded the finding of the MT Orkim Harmony as a glowing example of cooperation between Southeast Asia’s authorities. The Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) and Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) had secured the tanker; the Vietnam Border Defence Force (VBDF) had apprehended the pirates on their coast; the abandoned tugboat used in the hijacking was found by Indonesian Navy’s Western Fleet Command’s (KOARMABAR) Quick Response team. It was, it seemed, a triumph.

“It was only through working together with neighbouring countries that we successfully located the hijacked vessel,” said Najib, adding that the case served as a model for future coordination and cooperation between agencies.

Trouble in paradise

But the MT Orkim Harmony episode also highlighted some of the fractures in the regional agencies’ somewhat tenuous relationships with one another. When analysed closely, what initially seems like a success story sheds light on the tears in the fabric of Southeast Asian authorities’ allegedly cooperative alliances.

Within hours of locating the ship, for example, the Malaysian navy – quick to quiet the critics who had likened the loss of the MT Orkim Harmony to the missing Malaysia Airlines flight 370 – announced that they had found the ship, knew it had been renamed and were tracking its every move. But even pirates read the news; the hijacking team knew they had been located almost immediately.

The announcement came very close to endangering the lives of the crew members still held aboard the MT Orkim Harmony. In a personal account published days after his rescue, the ship’s captain, Nor Fazly Sahat, described the eight days he and his crew spent as hostages. According to his account, the pirates – once they knew they were being tracked – began acting erratically, and he feared they were considering using the crew as human shields when the authorities came calling.

“[A] critical time was when they realised they were cornered. They became agitated and nervous,” he wrote for the Malay Mail. “It was worse than the day when they first boarded… things might have ended up differently, but I’m glad it did not come to that.”

According to a maritime security researcher who agreed to speak to Southeast Asia Globe under cover of anonymity, the seemingly uncalculated decision by the Malaysian navy to publicly divulge sensitive updates on an ongoing case was made to cement Malaysia’s leadership in the case. As Indonesian officials appeared ready to take the reins on the hijacking, which involved a pirate crew of Indonesian nationals, the Malaysians wanted to make it clear that they remained at the head of the investigation.

The tension between the two countries’ authorities came into the spotlight when Indonesia, who claimed to have arrested the mastermind behind the hijacking, insisted on trying to extradite all eight of the pirates who had been arrested in Vietnam. Malaysia had already requested extradition of the same prisoners, and as the months ticked by, Vietnam chose to deny Indonesia’s request while simultaneously accepting Malaysia’s.

As Malaysia tried the eight MT Orkim Harmony pirates in its own courts, nearly a year after their arrest, Indonesia seemed to lose its interest in tracking down hijacking mastermind Albert Yohanes. Although it was widely reported that Yohanes was in custody in Indonesia and expected to be extradited to Malaysia, no updates on the alleged mastermind’s case, location or anticipated trial have been released in the past three years.

Lost at sea

Despite the overtones of competitiveness and an apparent unwillingness to concede authority, Southeast Asia’s maritime organisations and authorities have been working together – at least in some capacity – for several years now. The region’s marine authorities have met with the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) Piracy Reporting Centre (PRC) on “numerous occasions… to discuss cooperation and ways to reduce and stop incidents”, according to IMB PRC duty officer Tanasegaran.

It is this cooperation that has had the greatest impact on limiting the instance of piracy in the region, contributing to recent years’ annual decrease in reported piracy incidents, Tanasegaran said. “The [hijacking] incidents in Asia are dropping due to the increased patrols in the high risk areas, particularly in Indonesia,” he wrote in a recent email, describing some of the prevention tactics that have been employed.

Additional patrol boats have been deployed to ten “hot spots” identified in the region, and boats travelling through these areas are provided with the coordinates of these patrols at all times, he noted. Intelligence agencies in the Philippines have begun coordinating with IMB PRC as well, providing intel on potential attacks by militants in nearby waters.

When asked about the allegedly ongoing practice of hijacking for product theft by well-funded pirate syndicates, Tanasegaran said simply that product theft was no longer an issue in the region. “For hijacking of small product tankers for their gas oil, that started in 2014 in the South China Sea and off the coasts of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore… [but] these hijackings stopped abruptly in late 2015 after some of the criminals were arrested by local authorities in Malaysia and Indonesia,” he said, referencing the MT Orkim Harmony case.

As if an afterthought, he conceded that there had been multiple hijackings reported in 2017 – but otherwise, he insisted that product theft was no longer a pressing issue for the region. He did not mention the two attempted hijackings that occurred in 2018, each of which resulted in suspects being arrested by the MMEA, nor did he mention the third incident of cargo theft that occurred in 2017.

“I was surprised by the general leniency with which pirates are sentenced in Indonesian courts. In my opinion this is woefully inadequate”

London School of Public Relations researcher and programme director Adam Fenton

“As for other areas, whenever the IMB PRC receives [word of an] abnormal number of incidents from ships at sea, [we] will officially inform the respective government agencies to stop the menace,” he added. “Usually, by increasing patrols or looking at the source, we will stop or reduce such incidents.”

But increasing patrols is not as easy a task as the IMB makes it out to be, nor are the patrols always effective; even when fully mobilised, it is still a tough task to monitor the vast stretch of waters that surround Southeast Asia, as the week-long hunt for the MT Orkim Harmony made clear.

Above all, patrols are costly. The amount of money being invested in anti-piracy patrols has long been quite high: as of the end of 2017, the MMEA was investing an average of $23.2 million annually into its patrols, while the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) budget came in at about $2.3 million. Every time the Philippine Coast Guard deploys a sea marshal to escort a commercial ship through its waters, the escort comes with a price tag of between $13,000 and $15,000 – and it’s the same for every country offering patrols of their waters.

Across the region, there’s the belief that some countries – especially Singapore – are benefitting from the economic efforts of their neighbours, according to a report by Oceans Beyond Piracy; this in turn encourages countries to rein in their patrolling efforts, unwilling to spend the money that other countries appear uninterested in investing.

On top of this, even as regional authorities across Malaysia and Indonesia work to share intelligence regarding potential pirate attacks, their ships are not able to follow pirates into their neighbours’ territory. Even if a patrol were to be in hot pursuit of a pirate-hijacked ship, it would need to wait for the all-clear from country whose waters it planned to enter before being allowed to follow the ship. This has been the case for years – and no tangible improvement has yet been officially discussed.

A hidden problem

In a 2012 report entitled simply “Piracy”, writer and analyst on naval affairs Martin Murphy wrote that there are several key factors that encourage piracy in any region: “legal and jurisdictional opportunities, favourable geography, conflict and disorder, under-funded law enforcement and inadequate security, permissive political environments, cultural acceptability and maritime tradition, [and] reward.”

There’s not much to be done for geography – the waterways in Southeast Asia are a prime target for piracy simply because they are crucial for both regional and worldwide maritime trade, teeming with ships ferrying expensive goods from one city to the next. There have also been considerable strides toward increasing funding for anti-pirate patrols in recent years, though the funding for these patrols will always remain finite.

But when it comes to the other categories, there is a fair amount of improvement to be made in Southeast Asia – especially in the area of “permissive political environments”, as maritime security researcher Ioannis Chapsos was quick to mention when speaking with Southeast Asia Globe.

An overarching problem for Southeast Asia is, quite simply, that its authorities don’t want to admit they have a pirate problem. This kind of confession would leave a country open to international scrutiny and even international intervention, as occurred off of the coast of Somalia a decade ago, and Southeast Asia’s authorities would rather avoid that sort of attention.

When agencies arrest alleged pirates, then, they don’t like to call them pirates, classifying them instead as “armed robbers at sea”, Chapsos said. To bring a pirate to trial would be to concede to international sentencing laws against pirates; bringing an “armed robber at sea” to trial allows every aspect of sentencing to fall under the coastal state’s jurisdiction.

“When they speak about piracy, they actually refer mainly to armed robbery. This is exploited by potential pirate groups, and – alongside corruption and illegal networks – further fuel and enable piracy to occur,” Chapsos added. “Both of these are enabling factors for piracy, since without the illegal networks, pirates can’t siphon their plundered goods in the market, and corrupt officials are key to this for obvious reasons.”

According to ReCAAP, more than 90% of maritime incidents that took place in Southeast Asia in 2018 fell under the category of “armed robbery against ships”, rather than pirate hijackings. The distinction becomes especially important when it comes time to bring maritime offenders to trial.

Legal loopholes

Across Southeast Asia, the sentences handed down to alleged maritime offenders are wildly different in scope and severity. It is not uncommon for maritime offenders tried in Malaysian courts, for example, to receive lashings in combination with years spent in prison. In Indonesia, sentencing is often seen as more lenient, with offenders serving a small fraction of their potential 15-year jail terms.

Adam Fenton, a researcher and programme director for the London School of Public Relations in Jakarta, said that his deep-dive into Indonesia’s approach to sentencing its pirates had led him to conclude that Indonesian courts are “overly soft”.

High profile cases that receive enough attention will result in significant jail time, as in the well-reported case of Eva Novensia, a successful businesswoman who funded the failed hijacking of Singaporean tanker MT Joaquim in mid-2015. Novensia was handed down a sentence of seven years – much longer than the typical sentence, though still not close to the full amount of time she could have legally served. Other alleged pirates – as in the case of the elusive Albert Yohanes – never see the inside of the courtroom.

“I was surprised by the general leniency with which pirates are sentenced in Indonesian courts. Apart from the Eva Novensia case, the average was around 12 months, even for crimes that involved violent acts,” Fenton told the Globe. “In my opinion this is woefully inadequate – it does not achieve any of the fundamental goals of criminal punishment, particularly general and specific deterrence.”

He added that is often difficult to determine why a sentence has been handed down in the first place, with Indonesian judges writing limited explanations for their decisions – a caveat which allows plenty of wiggle room for potential bribery to sway an official opinion.

“I can’t really comment about corruption in piracy cases in particular… however, it is no secret that Indonesia’s judiciary is largely corrupt all the way up to the Supreme Court level,” Fenton added. “So it certainly wouldn’t surprise me if commercial factors were involved.”

By comparison, sentences on the books in neighbouring Singapore are far harsher, with a mandatory death sentence being handed down where life-threatening violence is involved. But according to several sources, Singapore is less interested in admitting it has a piracy problem than even Indonesia; it maintains a low radar in the piracy realm, not entertaining any major arrests or investigations.

When detective Karsten von Hoesslin spoke to Southeast Asia Globe about the business model behind modern-day piracy, he said he had personally discovered evidence that piracy documents were being forged on Singapore’s shores – but when he approached the relevant officials to present his findings, “they just denied it”.

“Singapore is one of the dirtiest places ever in terms of money laundering. And when you follow the money, that’s where you end up”

Detective and response consultant for the Remote Operations Agency, Karsten von Hoesslin

On another occasion, he said he had evidence that a pirate syndicate had a mole in a Singaporean agency, resulting in a pattern of hijackings of ships leaving the same Singaporean port – but again, when he contacted the authorities, “their response was ‘well, you know, the reason they’re always going after [these ships] is because our fuel, our cargo is better than anywhere else in Southeast Asia’”, he said.

The undercover agent who von Hoesslin contacted also verified the inaction of the small island nation: “Singapore is one of the countries not willing to cooperate,” he said, “If [a member of a pirate] syndicate is their citizen.” In the same vein, the semi-active pirate interviewed by von Hoesslin also noted that Singapore remains a hub of economic activity for money laundering of pirate plunder.

“Singapore is one of the dirtiest places ever in terms of money laundering,” von Hoesslin added. “And when you follow the money, that’s where you end up.”

When contacted, Singapore’s Ministry of Finance, Anti-Corruption Unit, and Coastguard declined to comment. Southeast Asia Globe was able only to get in touch with the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), which recently made headlines for several high-profile arrests in its crackdown on illicit activity in the country’s financial sector.

“MAS is firmly committed to safeguarding Singapore as a clean and trusted financial centre. Combatting money laundering, terrorism financing and proliferation financing are priorities for MAS,” wrote Denise Gan, MAS deputy director of communications, when asked about her organisation’s attempts – if any – to crack down on pirate syndicates’ potential money laundering through Singapore.

“We require all our financial institutions, including banks, to have sufficiently robust controls to detect and deter such illicit activities. We also partner with the industry to bolster their defences, by engaging them on emerging risks, evolving criminal typologies and industry best practises,” she added.

Gan could not provide any examples of MAS investigating any illegal activity related to piracy.

For Chapsos, the unwillingness of countries like Indonesia and Singapore to conduct fair investigations and bring their pirates to court is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to poor practices that encourage piracy across the region.

“It is not very realistic to expect that corruption will disappear, but [governments] could still focus on… giving a more clear mandate to specific agencies to investigate and suppress the crime… [and] not turning a blind eye to existing crime with international dimensions, like piracy, for political reasons,” he said.

“[These changes] could act as a deterrence for wannabe pirates,” he added.

But as long as reported pirate hijackings remain low in number, it is unlikely that any of these changes will be put into practice. Perhaps, when a spike in pirate activity begins to make headlines, the region’s governments will realise the cost of turning a blind eye.