The date is unclear – just another ominous day in the slow grind of the Vietnam War.

Infantryman Dwight Allbee was patrolling outside Phước Vĩnh Combat Base in the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam, as it was better-known. A private in the US Army 26th Regiment’s 1st Battalion A Company, Allbee monotonously hacked his way through leech-infested jungle.

Emerging into a glade, Allbee was ordered to stop, roll down his sleeves and don his gas mask. His buddies followed suit. Word came down the line that the point man had disturbed a beehive and that the soldiers up front were to be “dusted off”.

Phước Vĩnh, in the hinterland province of Đồng Nai north of what was then Saigon, was a hotly contested region where fighting raged between the allied US/Army of the Republic of Vietnam(ARVN) forces and their Vietnamese communist rivals. Since its construction in mid-1965, patrols out of the base were regularly ambushed, with terrifying improvised explosive devices hidden on the jungle floor and deadly snipers peering through their gunsights from the trees above.

Halted in the ambush-prone clearing, Allbee and his fellow soldier Carlos Arambula heard the familiar drone of a turboprop aircraft flying overhead. Ordinarily, this would have been an innocuous event. But at the time, Allbee recalled, Arambula said he felt a light mist settle on the back of his neck.

Information trickled down the line that the point man needed to be evacuated due to bee stings. But there was to be no medivac and, as Allbee passed the supposed beehive, there was no sign of bees.

Allbee and Arumbula kept in touch after the war, when Allbee learnt that his friend had developed a bleeding lesion on the back of his neck that never fully healed. He died a few years ago.

“I did not learn what Carlos died of, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was cancer, diabetes, or both,” Allbee recalled.

“There was a special Air Force outfit that flew defoliation missions. They were called the Ranch Hands, and their motto was, ‘Only we can prevent forests.’” – Michael Herr, Dispatches, 1977.

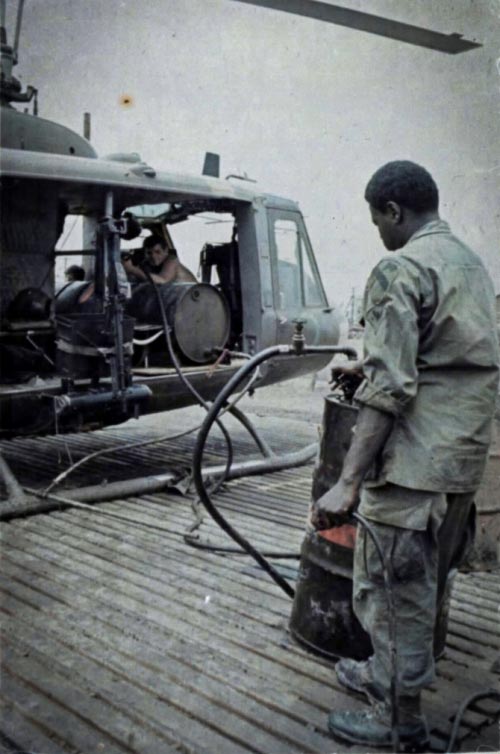

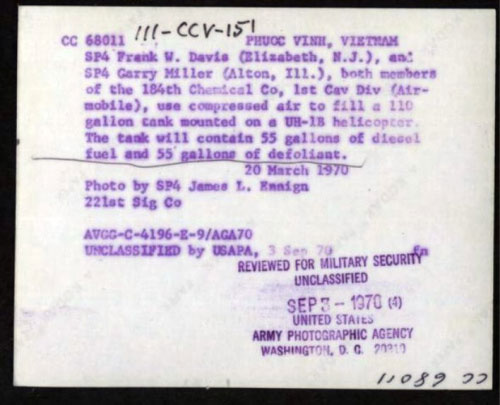

From 1962 to 1971, the US Air Force sprayed nearly 19 million gallons of toxic herbicides and defoliants across South Vietnam as part of Operation Ranch Hand, at least 11 million gallons of which was Agent Orange.

“I saw 150-foot tall canopy jungle areas that, a month or so later, were eerie. Just some stumps… piles… and no discernible leaves on trees or plants”

Joseph Dirvin, Vietnam War veteran

According to the Aspen Institute, a US think tank, Đồng Nai was the most heavily sprayed province in South Vietnam. 1,785,897 gallons were sprayed there during the 1960s, an area covering 2,413 square kilometres – 41% of the province. The second and third most sprayed areas were Bình Dương and Thừa Thiên-Huế provinces.

The three provinces also hosted the US/ARVN’s largest air force bases in Biên Hòa, Đà Nẵng and Phù Cát, populated by American and South Vietnamese soldiers.

Joseph Dirvin was in the same division as Albee and also experienced Agent Orange up-close and personal. Dirvin heard of soldiers pouring 55-gallon drums of dioxin through the open doors of cargo aircraft in mid-flight. Their only protection – gauze face-masks.

“I do not know of any training for any ARVN or American ground units,” Albee said. “We were not informed about the spraying and I don’t remember any discussion about defoliated areas.”

Dirvin witnessed the rapid and devastating impact Agent Orange had on the jungle and environment.

“I saw 150-foot tall canopy jungle areas that, a month or so later, were eerie. Just some stumps… piles… and no discernible leaves on trees or plants,” recounted Dirvin, who suggested that the local water supply had also been been contaminated

“Water given to us from local sources had such an off and odd smell it reminded me of growing up near to chemical production plants a few blocks away in Philadelphia.”

In his 1989 study of Agent Orange, Gregg Knowlton, director of research at the Oklahoma Agent Orange Foundation, described Phước Vĩnh as “the ‘Groundwater Zero’ of the chemical war in Vietnam”.

Water in Phước Vĩnh contaminated with Agent Orange – which contained in Knowlton’s estimation “the most toxic dioxin ever known to man” – supplied forward combat bases throughout Đồng Nai Province.

Knowlton found that the highly permeable soil and groundwater flow to the south and the west meant that water drawn from Phước Vĩnh was contaminated by Agent Orange sprayed on suspected communist camps to the north and the east.

“The veterans who were physically present at ‘Phước Vĩnh Groundwater Zero’ are, undoubtedly, the most likely to show high-level body-burns of these compounds, even today,” said Knowlton.

Left incredulous by “studies” carried out by government agencies that were seemingly unable to find veterans affected by Agent Orange, Knowlton retorted that veteran victims “can, indeed, be found today, through service organisations and various grassroots networks addressing the issue”.

“No Agent Orange in her family, we checked the records, you can never be too careful.” – Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale, 1986

Over almost five decades since its use in Vietnam, exposure to Agent Orange has killed or maimed approximately 400,000 US soldiers and affected an estimated 4 million Vietnamese.

The chemical’s reputation has permeated throughout Western and Vietnamese history. Permanent body-burns and incurable lesions were common effects of exposure to Agent Orange.

However, since the Vietnam War ended in April 1975, almost 2.8 million American ex-servicemen have contended with much more than lesions and burns. The consequences are deeper, broader and last longer than anyone imagined.

The US Department of Veteran Affairs website lists diseases linked to Agent Orange – a harrowing catalogue of terminal conditions such as soft-tissue sarcoma, Hodgkin’s disease, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, prostate cancer, type 2 diabetes, leukemia and Parkinson’s disease. All have been recognised as resulting from service in Vietnam and are eligible for compensation.

In 1991, illnesses caused by Agent Orange were put under scientific review through the Agent Orange Act. The act authorised special health benefits for “boots on the ground troops” who were exposed. However, flight and ground crews that served on aircraft spraying Agent Orange were only added to the scheme in 2017.

“Of the many things I continue to struggle with, regarding my Vietnam experience, is the fact that the military and the government exposed us to the chemicals knowing, I believe, that we would be harmed.”

Dwight Allbee, former US army infantryman

Even worse, “blue water Navy” veterans, so-called for service on the open ocean as opposed to “on the ground” and inland waterways, were not included in the benefits programme until 2019.

Allbee has spent most of his postwar civilian life living on benefits he receives from being exposed to Agent Orange.

“I have Agent Orange presumptive prostate cancer, for which I receive compensation,” said Allbee.

“The VA [Department of Veteran Affairs] connects my prostate cancer to Agent Orange exposure. There is little, if any, history of prostate cancer in my family and definitely not with my father or two grandfathers.”

A study by ProPublica, a US investigative journalism website, suggested that veterans exposed to Agent Orange were a third more likely to have children suffering birth defects than veterans who were not exposed.

“My two children have the type 2 diabetes that can be controlled by diet,” Allbee said.

“However, there is a strong history of diabetes in both my wife’s family and my family. I have a grandson on the autism spectrum, but his father may also have been on the spectrum though he was never diagnosed as such.” Although not necessarily down to Allbee’s exposure to Agent Orange, the nagging worry that even his grandchildren have been affected compounds an already disheartening reality.

Benefits have been doled out periodically since veterans noticed an increase in post-war deaths among their ranks: $180 million in 1984; $240 million in 1988. The total payout rose to $16.2 billion by 2010 and $24 billion by 2015. It is estimated that $5.5 billion will be paid over the next ten years to blue-water navy veterans.

“I also have chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” said Allbee. “However, of the many things I continue to struggle with, regarding my Vietnam experience, is the fact that the military and the government exposed us to the chemicals knowing, I believe, that we would be harmed. It is the element about which I remain angry and feel most deceived about.”

“But all that is crushed by war is more lasting, lasting longer than all the ruins of war and conquest.” – Báo Ninh, The Sorrow Of War: A Novel of North Vietnam, 1996.

The exact date is unclear – just another ominous night in the slow grind of the Vietnam War.

Thủ Thành Lương, an engineer in the Regiment 270 of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), the North Vietnam army, tried to get some sleep on his first night travelling down the Ho Chi Minh trail through Laos.

After enlisting in the PAVN in May 1972, Thủ Thành Lương walked from his hometown Lạng Sơn on the northern border with China to Hanoi. From there, he traversed the Ho Chi Minh Trail, passing the demilitarised zone through Laos, on the way to what the PAVN designated as Military Zone 5, which included the areas Thừa Thiên-Huế, Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi and Đà Nẵng.

After a thousand-mile journey on foot under constant threat of US airstrikes, Thủ arrived in Military Zone 5 in August during vicious South Vietnamese and US counter-offensives.

Thủ was part of the Easter Offensive, launched in spring 1972 and designed to retake large areas of land ahead of the Paris Peace Accord negotiations. Initially a bold and potentially crippling plan emulating the 1968 Tết Offensive, the offensive quickly floundered due to inept tactics as it came under sustained American bombing and took heavy casualties.

For the rest of the war, Thủ was an unwitting target, based in Thừa Thiên Huế and Quảng Nam, the third and seventh most-sprayed provinces with Agent Orange.

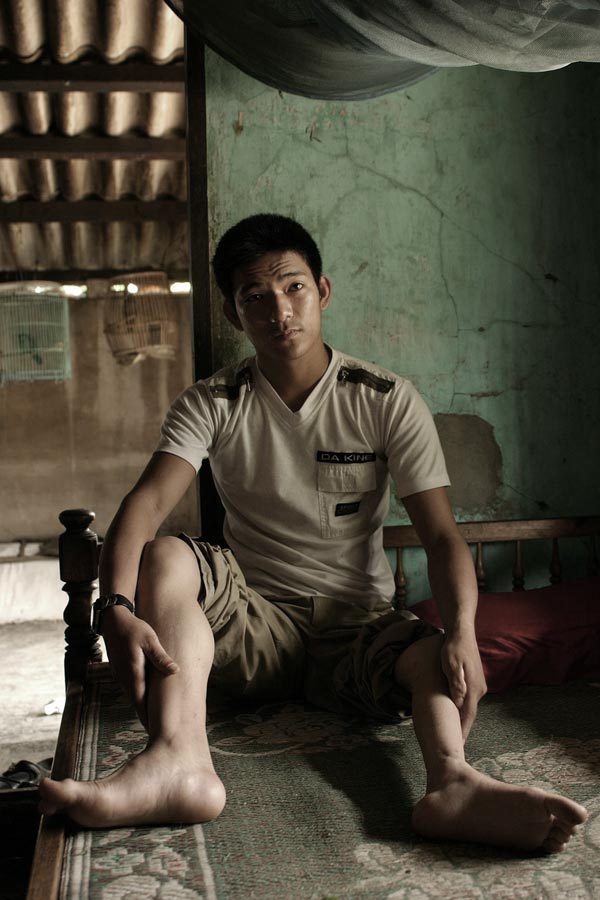

After returning home in 1976, Thủ married and had a daughter, Hạ Thụ Lượng, in 1982.

Soon after she was born, though, the new parents began to notice abnormalities in their daughter’s growth.

After a number of medical inspections, it was confirmed that Hạ had a birth defect linked to her father’s exposure to Agent Orange. The disability has haunted Hạ Thụ Lượng throughout her 37 years, stunting her growth to 80 centimetres and leaving her dependent on her family.

“Vietnam and America have normalised their relationship. But, I think the US government should compensate Vietnamese victims as well as American ones, for the sake of legal justice”

Thủ Thành Lương, ex-North Vietnamese army

“In reality, Lạng Sơn Province has over 4,000 people who were exposed to and are victims of Agent Orange,” Thủ said.

Since his daughter was born, Thủ has campaigned to raise awareness of Agent Orange in Lạng Sơn, attending annual meetings on the subject.

“My daughter is one of the five worst cases in Lạng Sơn,” he continued. “Medical tests confirmed that she has lost 81% of her health. I have lost 71% of my health.”

Multiple compensation claims to the US Supreme Court from Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange have been repeatedly denied, leaving the Vietnamese government and human rights groups to largely cover the cost and effort of providing for those suffering from lasting effects.

This is despite a poll commissioned by Associated Television News showing that 51% of Americans agreeing that US manufacturers of Agent Orange should compensate Vietnamese victims.

“She is glad she receives 50 dollars a month for compensation,” Hạ’s sister explained. “We often tease her that that is her salary and that she is the richest person in the family.”

“But, she doesn’t know 50 dollars can’t compare to the opportunity of growing up and living as a normal person,” she continued. “Like going to college, having a boyfriend and getting married with kids.”

Who is to blame? The administrations of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon? Top-brass military personnel, special advisors, or scientists assigned to the war effort in Vietnam?

In a 1988 letter to Senator Tom Daschle, who helped push through the 1991 Agent Orange Act, Dr. James Clary, an associate professor of Ecology at the US Airforce Academy during the war, admitted that he and others knew in advance that Agent Orange would lead to contamination.

“When we [the US Airforce] initiated the herbicide programme in the 1960s, we were aware of the potential for damage due to dioxin contamination in the herbicide,” Clary wrote, conceding that they overlooked the possibility that US soldiers could be affected.

“However, because the material was to be used on the enemy, none of us were overly concerned. We never considered a scenario in which our own personnel would become contaminated with the herbicide.”

What of businesses commissioned to manufacture Agent Orange, distanced from policy but fixated by profit? Of the dozens of companies involved, Agent Orange was made primarily by Dow Chemical and Monsanto Company.

In a presumed attempt to clarify its involvement with Agent Orange, Monsanto dedicates a page on its website outlining their background in producing the spray from 1965 to 1969. A “unique mixture” of “two common herbicides,” the wording reads more like a cocktail recipe than a deadly toxin, while the justification for producing Agent Orange – to “save American lives” – rings hollow.

Monsanto was acquired in 2018 by Bayer AG, a German pharmaceutical company. Even so, the repercussions of Monsanto’s involvement in the Vietnam War are still being felt – and could now be Bayer’s burden to bear.

The first lawsuit against Monsanto over the weed-killer Roundup was filed in 2016 by 44-year-old groundskeeper Dewayne Johnson. The number of similar lawsuits claiming that the glyphosate-based herbicide causes non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer, has since topped 18,400. It was claimed by people close to the negotiations that Bayer proposed paying US$8 billion to settle the lawsuits, though according to Reuters, mediator Ken Feinberg said that reports of a settlement being discussed were “pure fiction.”

Though both are herbicides, Roundup and Agent Orange were used very differently: the former to rein in and spruce up overgrown gardens, the latter sprayed recklessly as a weapon of war. But today’s Roundup compensation claims echo past wrangles over Agent Orange, with manufacturers of both reluctant to admit any wrong-doing.

Bayer quickly backed an April 2019 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report, claiming that glyphosate does not cause cancer “when proper application procedures are followed”.

On 30 April, US News and World Report described how US Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue “cheered” the EPA findings, saying it was Perdue’s belief that the report was science-based and that glyphosate was necessary for the future of mankind.

“If we are going to feed 10 billion people by 2050, we are going to need all the tools at our disposal, which includes the use [of] glyphosate,” Perdue was reported as saying.

Perdue’s comments amounted to a member of the US government endorsing a carcinogenic chemical without apparently considering any potential collateral damage – much as governments in the 1960s recklessly endorsed the use of Agent Orange.

For the families of those still living with the consequences of the US’ decision to unleash Agent Orange on the Vietnamese countryside, reopening old wounds can be painful. But what if they never healed in the first place? One could forgive Vietnamese families for harbouring a deep and irreconcilable bitterness over the impact of Agent Orange. Reparations paid willingly – by actors who, so far, do not deserve the tolerance shown to them – would at least acknowledge the admirable prudence of parents such as Thủ.

“War happened long ago,” Thủ reflected. “Vietnam and America have normalised their relationship. But, I think the US government should compensate Vietnamese victims as well as American ones, for the sake of legal justice.”