Smiling retirees, residents of a high-rise housing project, harvest healthy greens from a vertical vegetable farm for domestic use or for sale. Waste from the farm is burned to generate electricity. Leftover ash is sprinkled into the soil to act as fertiliser. Nutrient-enriched water – courtesy of fish excrement – is pumped from roof tanks to nurture the stacks of plant-filled tubes that adorn buildings shimmering with a sheen of greenery.

This urban utopia may soon become reality if Singapore’s powers-that-be give the nod to Home Farm – a proposed project that responds to two of the city-state’s most pressing needs. The first is catering to its rapidly ageing population; the second is how the country enhances its food security.

“Social behaviour, I believe, is a major driver of the way in which buildings need to relate better to and offer more to the city,” said Stephen Pimbley, director of Spark architects, the firm behind the project. “Home Farm is a good example of how connections can be made between two different functions that traditionally may not otherwise be connected.”

Post-war Singapore, much like Western countries, experienced a baby boom, and many in that generation have now passed the country’s retirement age of 64. The country’s median age is predicted to rise to 47 by 2030, up from 38.9 in 2013 and 24.4 in 1980.

Added to this, life expectancy lurched from 72.1 years in 1980 to 82.5 two years ago, putting Singapore just behind Hong Kong, Iceland, Italy, Japan and Switzerland in the longevity stakes. Add to this a falling birth rate and you have a situation where the ratio of young people available to look after senior citizens is diminishing.

The attitudes of the younger generation are changing too. “While most young singles will stay in their parents’ home, when they get married they prefer buying their own apartment, which often is close to their parents’ place,” said Mathew Mathews, senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. “Apartments are often not too large and it is clear that once children arrive there will not be sufficient space for everyone to be in the family.”

Pimbley hopes that Home Farm will support those at risk by bringing them into a socially sustainable environment that has a mixture of income types and family groupings “rather than a ‘mono cultural’ section of society”.

However, Pimbley was quick to stress that the project will not be “a forced seniors’ labour camp”. Not all residents would be expected to get their hands dirty, but they would have the opportunity for part-time work to assist with income support and social engagement.

As a fully urbanised entity, Singapore also faces the critical problem of food security. With little arable land, there is simply not enough space to grow crops. Even though about one quarter of its land area was covered in food-producing farmland as recently as the 1960s, those farms have long been cemented over. Today only about 0.5% of the country’s land mass is used for agriculture.

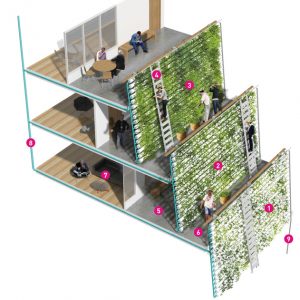

1) newly planted leaves 2) 15-day leaves

3) 30-day leaves 4) harvest ladder 5) covered walkway 6) harvest corridor 7) apartment 8) nutrient water 9) used water for recycling

According to Melissa Cate Christ, assistant professor at the division of landscape architecture, University of Hong Kong, the country is relatively food secure as it has a high level of purchasing power and a strong role as a trade and trans-shipment hub. However, it is at risk of food shortages caused by supply disruptions from its trading partners as a result of global, regional or local crises.

“These crises range from short-term emergencies such as disaster events, war or political conflicts, to longer term climate change-related issues such as changes in weather patterns resulting in drought or flooding, or the exponential increase in the global population,” she wrote in a 2011 paper entitled Food Security and the Commons in Asean: the role of Singapore.

In recent years, the issue of food security has been brought into stark relief by regional and global crises that have impacted Singapore. Outbreaks of the Nipah virus and bird flu in Malaysia have disrupted supplies of pork and eggs respectively, and 2008’s global financial crisis caused food prices to soar.

To address this, Singapore’s Agri-food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) is active in promoting modern intensive farming. Six agro-technology parks have been created in the north of the country, local farmers are being supported in efforts to boost yields and productivity, and much attention is being paid to vertical farming using aquaponic technology.

In 2010, the AVA inked a research agreement with Sky Greens, a company that has developed a prototype system of stacks of rotating soil planting troughs. Sky Greens bills this as the “world’s first low-carbon hydraulic water-driven tropical vegetable urban vertical farm” and claims that the production yield of a vertical farm is five to ten times more per unit area than a traditional farm. This technology is at the centre of Home Farm’s proposal.

“The Southeast Asian climate is perfect for growing plants on the surfaces of buildings. Other climates, such as that of north China, where it’s far too cold for three months of the year, would prove too difficult,” said Pimbley. “Singapore was chosen because of its lack of farmland and its appropriate climate for plant growth. The economics of vertical farming in countries that have an abundance of space and a mature farming industry, such as south China, would also not make sense for our model.”

One Singaporean company is already proving how aquaponic technology can benefit the country. In the heart of the city, ComCrop has constructed a farm on a 550-square-metre rooftop.

“We use land that is otherwise not used. And the sheer fact that we produce our products right next to the doorsteps of our potential customers means a giant carbon-based food print is reduced,” Comcrop co-founder Keith Loh told freshfruitportal.com. “It also reduces a lot of logistics in bringing imports into our country.”

Although this is a relatively small-scale project, the work needed to run it is labour intensive – a perfect model for Home Farm’s vision to provide retirees with engaging activities that could provide a source of income. ComCrop currently sells about 80% of its produce but is confident that it can build a larger market for its goods and has plans to scale up its operations at other locations.

“It would be great to see the food-producing urban garden of Home Farm as no longer a novel concept in senior housing but as a norm of living,” said Wing Yun Wai, architectural designer at Spark. “Just like when the escalator first arrived in the mid 19th Century, people were in awe of the moving steps. Nowadays, we no longer notice the design of an escalator as it has become part of our daily lives.”

It remains to be seen if Home Farm will be realised, but if it is, Pimbley would be happy to make it his home. “[The project] facilitates engagement with an open garden environment and provides purpose and self-esteem for those that engage with its activities,” he said. “I would love to live there – and I’m not that far off retirement age.”