Robots can do anything if they put their minds to it. Last year, Flow Machines, a research project funded by the European Research Council and coordinated by the Sony Computer Science Laboratory (Sony SCL), produced the world’s first pop song composed by artificial intelligence.

The team at Sony SCL fed more than 13,000 sheets of popular music into a computer, which analysed the rhythms, melodies and structure of the music and then used advanced machine learning to produce its own original melody based on its analysis (the lyrics were later added by a human). The result was “Daddy’s Car”, a song inspired by the Beatles that sounds no more formulaic than other hits topping today’s music charts.

While it would be a stretch to describe the song as evidence of a machine’s ability to create original art, the project goes at least part of the way toward undermining the sanctity of human creativity, spoiling the long-held belief that only low-skilled labour is under threat from automation. Today, acquiring strong technological skills may be enough to secure employment over a machine, but experts warn the same cannot be said for tomorrow.

In the eyes of Marc Tucker, president of the US-based National Centre on Education and the Economy and a researcher who has spent the past two decades analysing the world’s best-performing education systems, the rapid rise of artificial intelligence means that we must devote our development “to those things that are uniquely human”.

“The people who will succeed in the world ahead are the people who make use of their most human, non-cognitive capacities: their ability to relate to other people; their ability to communicate complex matters clearly; their ability to work in teams effectively [and] to lead others,” he told Southeast Asia Globe during a telephone interview from Washington, DC.

Tucker is in good company when he expounds the increasing importance of what are often referred to as ‘soft skills’. In 2015, a report by the World Economic Forum claimed that increasing automation meant that complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity would become the three most sought after workplace skills in 2020. Earlier this year, a similar report by the professional services firm Deloitte argued that a new wave of jobs brought about by automation was creating demand for “higher cognitive skills such as those that depend on management or human social interaction”.

To ensure students develop such skills, schools must teach students how to think, not what to think. But they must also understand that some of life’s most valuable lessons transcend the classroom setting and, thus, create environments that mimic real-life situations and encourage students to think on their feet, according to Tucker.

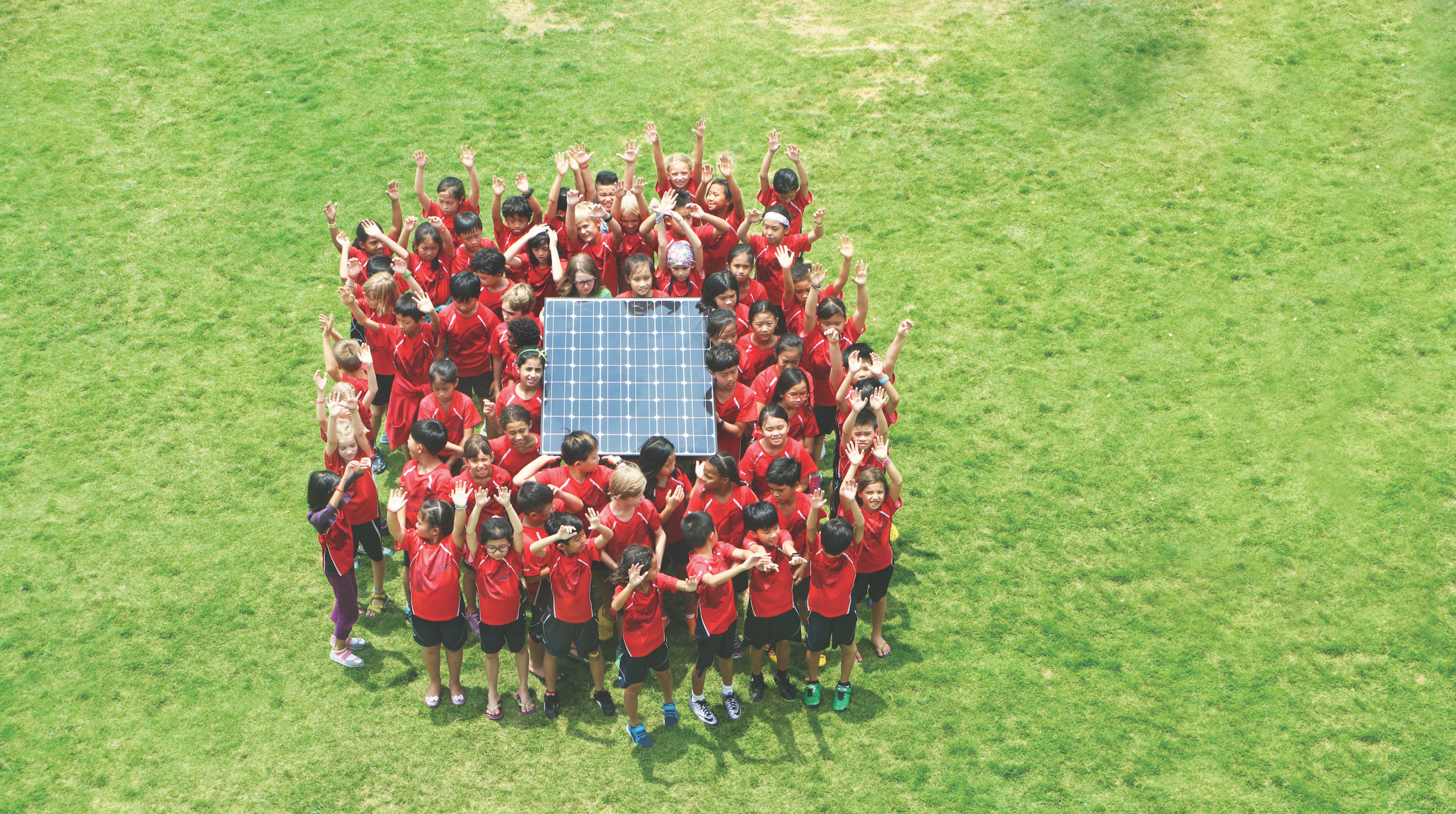

“In the West, when people think about schooling, they tend to think about what happens in classrooms, which is really the cognitive development of young people. But they think much less of what happens on the playing fields or what happens in sports,” he said. “In the future, the role of the school [should be] seen more holistically. Schools should develop a student’s character and values, as well as their thinking ability.”

Even technologically advanced Singapore, which was recently recognised as having the best education system in the world by the Programme for International Student Assessment, has been criticised for failing to adequately equip students with the requisite ‘soft skills’ to effectively contribute to the modern workforce. A year-long survey conducted by the Singapore Management University and JP Morgan and published in 2016 revealed that the city-state had for too long focused on teaching hard skills at the expense of nurturing the creativity of its students, undermining its goal of creating an innovation-driven economy.

Recent policies, however, would suggest that Singapore’s government is well aware of this skills shortage. In 2014, the country introduced a physical education syllabus that committed 10-20% of curriculum time in primary and secondary schools to outdoor education, signifying a commitment to a holistic approach to education. “It is about developing an enduring core of competencies, values and character to anchor our young and ensure they have the resilience to succeed,” the country’s education minister, Heng Swee Keat, said of the approach in parliament in March.

A growing number of schools in the region are implementing similar policies and increasing efforts to promote student wellbeing. During early years’ education, this can simply mean providing children with “opportunities to check in with themselves at different points in the day” or setting up areas for children to take time out from a class if they’re ever feeling overwhelmed, according to Kirsty Campbell, wellbeing leader at iCAN British International School in Phnom Penh.

All the things that people write about as 21st century skills, it’s all nonsense. Those are old skills”

In middle years, Campbell added, iCAN’s students take regular mindfulness classes where they practice meditation or learn other strategies to develop “emotional resilience”.

“Obviously the curriculum is rigorous and we talk about academic success,” said Campbell. “We’re just allowing them that space to talk about their feelings. And they’re lifelong tools.”

Schools struggling to develop their students’ soft skills need look no further than the history books for inspiration, according to Tucker. “If you go through the list of 21st century skills, they were all alive and well at [revered British private schools] Eton and Harrow in the 1890s, because what those institutions were all about was creating the future leaders of the British Empire,” he said.

“They needed to be great leaders. They needed to be great team members. They needed to adapt. They needed to set deadlines for themselves. They needed to have self discipline. All the things that people write about as 21st century skills, it’s all nonsense. Those are old skills.”