The Komodo dragon enjoyed a big bump in its global profile in 1956.

Renowned naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough introduced BBC audiences to the fierce predator in that year through a television segment, “Zoo Quest for a Dragon.” Attenborough’s familiar voice narrates black and white footage of one of the reptiles slinking across a forest floor, tongue darting as it catches the scent of a goat carcass suspended in a clearing by the scientist and his local guides.

“I hadn’t reckoned on him being so big, and to our dismay we saw that he could reach this hanging bait,” Attenborough says as Earth’s largest lizard dislodges slices of meat on its namesake island in eastern Indonesia.

In a practice that has since been outlawed, the dragon wanders into a handmade trap the humans have set. The camera offers a closeup of the incarcerated animal’s mouth and snout, a dangerous view without the rocks and sturdy wood preventing the menacing carnivore from doing anything more than peering into the lens.

“unfortunately, in the end, bureaucracy defeated us and we weren’t given a permit to export those dragons from Indonesia, so I’m afraid they’re still there.”

Safely back in a studio, Attenborough laments that “unfortunately, in the end, bureaucracy defeated us and we weren’t given a permit to export those dragons from Indonesia, so I’m afraid they’re still there.”

Indonesia is even more protective of its celebrity species now than at the time of its administrative triumph over the television personality, although recent news demonstrates the preservation effort has not done enough.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) last month placed the Komodo dragon on its ‘Red List’ of endangered species. The reptiles in Indonesia’s Flores Sea region – usually the hunters with a bite injecting bacteria and venomous saliva – could become victims of human actions, including man-made climate change inflaming a natural crisis.

“Rising global temperature and subsequent sea levels are expected to reduce the Komodo dragon’s suitable habitat by at least 30% in the next 45 years,” IUCN wrote, adding that “while the subpopulation in Komodo National Park is currently stable and well protected, Komodo dragons outside protected areas in Flores are also threatened by significant habitat loss due to ongoing human activities.”

Various organisations work to protect the dragons in their natural habitat on Komodo and four nearby islands encompassed by Komodo National Park. UNESCO has declared the park a World Heritage Site, while the Komodo Survival Program conducts research, education and habitat monitoring.

Tourism is restricted by the government in Jakarta, but not banned. After a July 2019 announcement that the island and its assortment of more than 1,700 dragons would be off-limits to visitors for a year, the government reversed itself only two months later. “There is no threat of a decline,” environment and forestry minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar told Reuters.

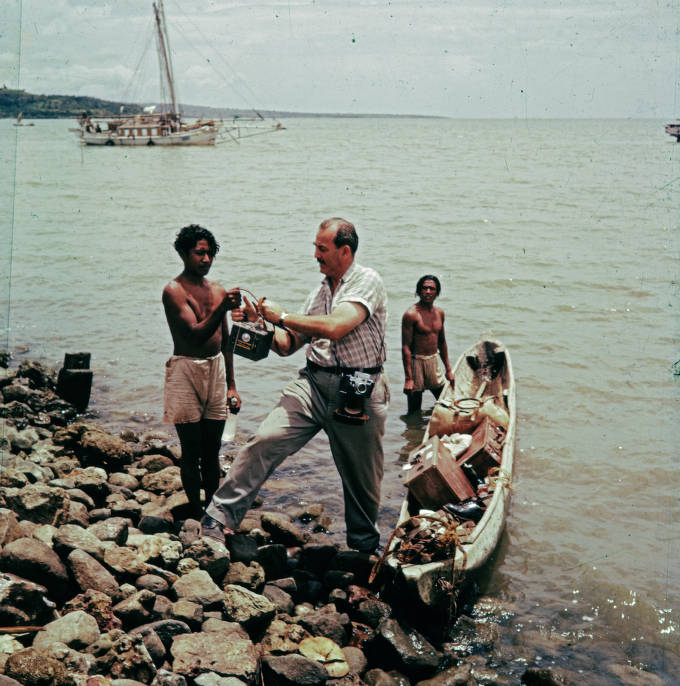

American photojournalist Harrison Forman also toured Komodo Island in 1956 to observe Varanus komodoensis, which scientists believe has persisted since its origin in Australia 3.8 million years ago.

Forman produced 150 images, including the photos featured here, showing the muscular lizards alone and in pairs navigating Komodo island’s muddy trenches and tall grass or devouring prey. He also snapped Indonesian hunters lashing together the slats of a dragon trap, the same type used by Attenborough’s companions, and captured the unspoiled beauty of Komodo’s coastline.

In the middle of the last century, Forman’s still photos and Attenborough’s film seemed to depict nothing more sinister than contact between wildlife and humans acting on their curiosity or traditions. Yet with the debut of the species on the endangered list, their images become part of the historical record of patterns that have pushed Komodo dragons closer to extinction.

Brian P. D. Hannon is an editor at Southeast Asia Globe. His articles are also on Twitter.