In late December, an 8-year-old girl was taken to a hospital in Ho Chi Minh City. When she arrived, she was already deceased.

Seeing wounds and bruises on the girl’s body, hospital staff contacted authorities. A police investigation found she had been violently abused for four hours by her stepmother, Nguyen Vo Quynh Trang, who beat her with wooden sticks, kicked her, slapped her and bound the girl to a chair, forcing her to sit up and study.

It wasn’t the first time the young girl was abused. Trang and the girl’s father, Nguyen Kim Trung Thai, admitted to beating her regularly and her body bore the marks. Neighbours often heard the girl crying in the upscale apartment complex in Binh Thanh District.

Trang was initially charged with abuse. After public outcry, she now faces murder charges. Thai has been charged with abuse and concealment of crimes.

The girl’s death brought renewed attention to the prevalence of child abuse in the country. Although progress has been made in protecting Vietnamese children, maltreatment rates remain high. A UNICEF survey found 68.4% of Vietnamese children between 1 and 14-years-old have been victims of domestic violence by their parents or caretakers.

Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation‘s programme manager To Thi Huong Giang said every hit suffered by a child is dangerous for their physical and mental well-being.

“The 8-year-old girl in Ho Chi Minh was beaten for four hours until she died but also one hit can make someone die,” Giang said. “Children who are physically abused have a lot of suffering… All of them have some impact more or less on their emotions or psychology.”

Between 2015 and 2019, 337 children died as a result of abuse, according to a government report. Among the deaths, 191 children were killed and 146 died as a consequence of the maltreatment.

Nhu Kieu Tran, who holds a doctorate in child and family studies from Leiden University, said the acceptance of harsh discipline in Vietnamese homes and schools is a barrier to improved child protection.

“We have the saying, ‘spare the rod, spoil the child.’ So we believe that harsh discipline is necessary to educate a good child, a child with good behaviour. Culturally, it has been our belief for thousands of years,” she said. “If corporal punishment is still tolerated then you will see that child abuse will still happen.”

Giang of Blue Dragon said she was born in a poor family and raised in a village where children didn’t know about their rights and often faced ill-treatment. She is now dedicated to improving the lives of Vietnamese children.

Blue Dragon is based in Vietnam’s capital city, Hanoi. Along with fighting human trafficking country-wide, the organisation helps children living on the streets secure food and safe housing and pursue opportunities for their futures.

Many of the children supported by the Blue Dragon team have suffered severe domestic violence, Giang said.

She recalled the story of a boy who tried to run away from the violence he suffered at home. After the attempt, his uncle chained him to prevent his escape. Blue Dragon found him living on the streets after he broke free.

“He was someone who was beaten very, very badly many times,” she said. “By the time that we reached out to him for the first time, one of his legs still had handcuffs.”

Other children she has helped have been locked in a small metal cage for animals and tied to a tree at the entrance of their family home.

Giang said these children have difficulty building trust after the hardships they have endured. Most have suffered multiple instances of abuse. Once they escape violence at home, life on the streets is dangerous and they are often beaten again, sexually exploited, exploited for their labour and face hunger daily.

“These children have layers and layers of trauma and stress,” she said. “It is not just one single incident that happened in their lives.”

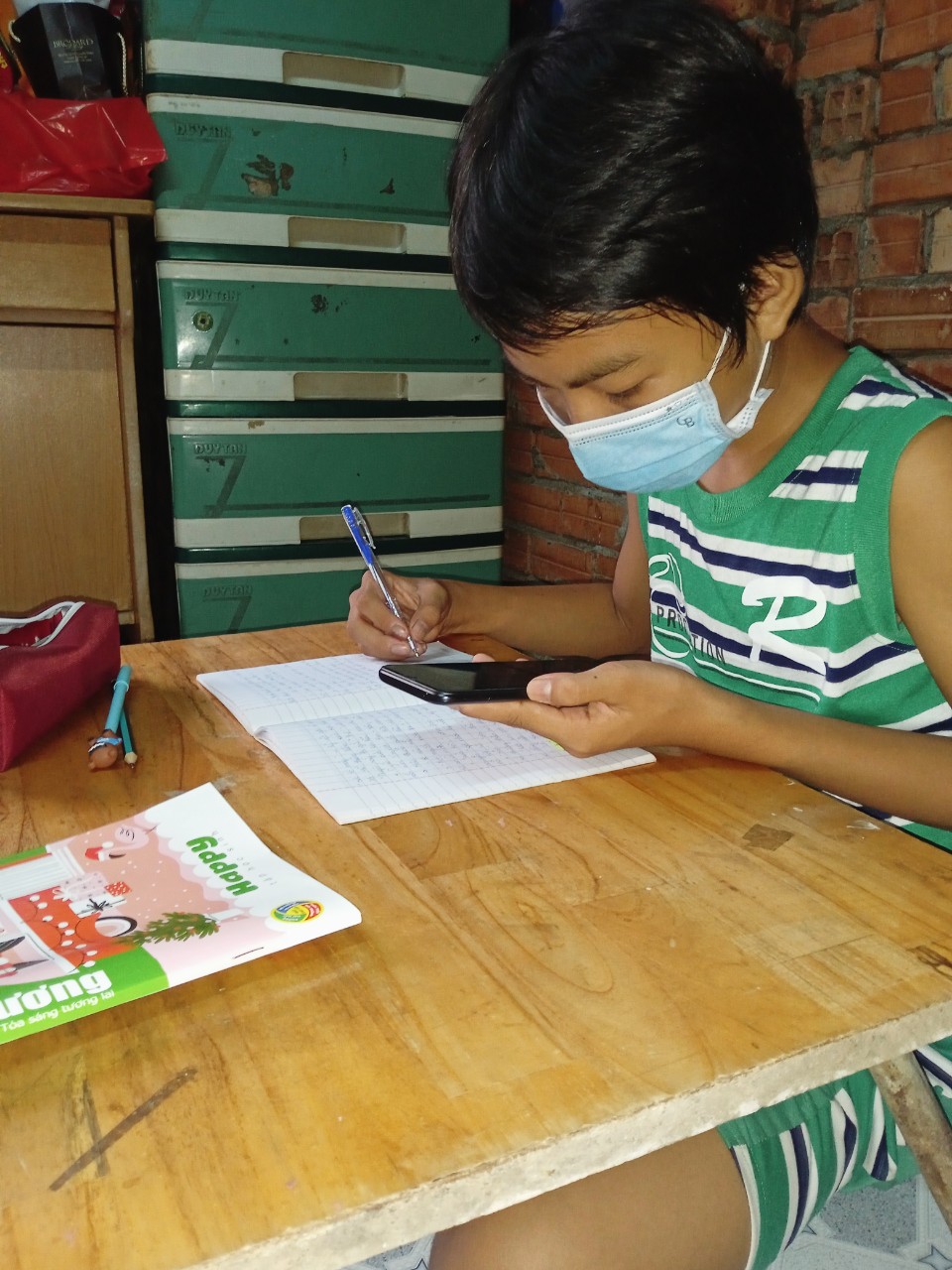

Experts fear the Covid-19 pandemic has increased the risk factors for abuse.

Damien Roberts, executive director of Saigon Children’s Charity, said school closures, lockdowns and economic hardship caused by the pandemic have exacerbated abuse. Further, opportunities to uncover abuse have decreased.

“I think it’s definitely given a lot more opportunity for abuse and it’s given the opportunity for abuse to be worse and more regular,” he said.

“When you couple those two things with the fact that the pandemic caused so much suffering and hardship and increased the stresses that many people face then I think in the case of abusers this is only going to make things worse,” Roberts said.

But as in-person learning resumes in Vietnam in the new year, school is not always an ideal safe haven. Students sometimes endure harsh physical discipline and other forms of abuse.

In northern Hai Phong in early February, a group of third-grade students were each hit 70 times with a wooden ruler on their backsides for not doing their homework. Local news outlet VN Express reported their teacher told authorities she did not hit the children herself but made their classmates perform the beating.

Teachers instructing students to hit classmates is not unprecedented. In 2018, a 6th grader in central Quang Binh Province was hospitalised after he was slapped 230 times by peers, Vietnam News reported. A primary school student in Hanoi was slapped 50 times the same year under teacher supervision.

A 2014 survey of 3,000 secondary and high school students in Hanoi found approximately 80% of respondents suffered abuse at least once at school, Thanh Nhien reported.

Along with news-making cases of child abuse at schools, corporal punishment as school discipline in Vietnam is not uncommon.

Thao Nguyen grew up in Ho Chi Minh City. The 32-year-old was sent to a small private kindergarten when she was 3 or 4-years-old. After returning home with bruises covering her body, her family pulled her out of the school.

As Nguyen remembered the reasoning for the abuse, “she was not a good kid” and didn’t finish meals or take naps at the same time as other children.

“The teachers were really mad at me and they hit me,” she said. “I don’t really remember much but my auntie told me that I came home with my full body full of bruises.”

In elementary school and high school, Thao said she saw students hit by teachers. As a good student with high scores, she avoided physical punishment.

Giang also has seen the harsh discipline still meted out on school children. One day, her daughter came home with marks on her face.

“It happened at my child’s kindergarten,” said Giang, who asked how her daughter got the marks. “Finally, she told me the teacher beat her… I take that as a thing I do not accept. “

Giang said the killing of the 8-year-old girl in Ho Chi Minh City is a heartbreaking example of the consequences harsh punishment can have on a child.

“She is dead because of punishment, because of abuse,” Giang said. “It must change.”

Despite witnessing the trauma experienced by some children through her work, Giang said she is encouraged to see the improvements made in Vietnam to protect children.

Vietnam’s National Assembly provided a legal foundation for children’s rights in 2016, Vietnam News reported. The law ensures children’s right to be protected from abuse including sexual harassment, violence, exploitation of labour, kidnapping and abandonment.

The next year, call centres were added for the country’s child protection hotline and the eight-digit number was shortened to 111 to be easier to remember. The updated hotline received 500,000 calls in 2021, according to Vietnam News.

Among the efforts of government and child protection groups, some initiatives have been made by young people themselves.

Tran Phuong Dung set up the Angels’ Halos Organisation in early 2020 when she was in 11th grade. Mostly working with teens, the nonprofit offers counselling services and solutions for struggling students.

“Most parents still keep the old way of thinking, they think hitting can help their child be better,” she said. “Teenagers are easily vulnerable but dare not tell people.”

Tran, the child and family studies expert, conducted multiple studies that identified a high prevalence of physical and emotional discipline.

“I thought that I must do something else to help to reduce the situation,” she said.

There are two primary solutions Tran would like implemented to improve child protection in Vietnam. First, parents and teachers need to be trained in replacing harsh discipline with positive discipline.

Since 2018, Tran has worked with Save the Children, an international child protection organisation with a base in Vietnam, to train parents and facilitators in a technique called positive discipline in everyday parenting. The approach is based on child rights and evidence on childhood development.

“If we want parents and teachers to stop using hard discipline we must provide them something else,” she said.”Positive discipline is very important. We can help many children.”

The most ambitious change Tran would like to see implemented is banning corporal punishment in Vietnam. She points to a global initiative to end all corporal punishment of children. Although she said much work is needed to reach this goal, she hopes Vietnam will join the 63 countries which have fully banned corporal punishment.

Tran Nguyen Phuong Thao, a teaching assistant at an English-language centre in Ho Chi Minh City, said hitting kids as a form of discipline is never a good solution.

“Hitting just makes them more scared,” Thao said. “They just try to fix the mistakes because they are scared, not because they understand why they are wrong.”

Although the cause of death of the Ho Chi Minh City girl went beyond physical discipline, Tran said, acceptance of corporal punishment allows violence against children to occur and potentially lead to deadly outcomes.

Without a legal ban on corporal punishment, neighbours and teachers who see a child being hit by an adult will not have recourse to inform authorities or tell the adult to stop, she said.

“[The stepmother] hit the child for hours. It is not discipline at all, clearly it is abuse. But because they tolerate corporal punishment she had a reason to use violence with the child,” Tran said.

“I would really like to see Vietnam in the future prohibit corporal punishment,” she added. ”It will be a lot of work but we have the vision.”