The race is on to shape development of the region’s digital sphere. Noted by some to be the ‘last bastion of freedom,’ the internet can also be seen as a lawless territory.

This digital world exists both in anarchy and in regulation, which comes as a problem in Southeast Asia where the digital space is still in its relative infancy.

Around 70% of the population in ASEAN member states now have internet access and, as a result of Covid-19 lockdown, there was an increase of 40 million new internet users.

Paling in comparison to the European Union’s internet penetration rate of 91%, the penetration rate in Indonesia, the largest country in Southeast Asia, stood at 73% in January 2021. This also trails behind Malaysia at 84% and Singapore with 90%.

The Indonesian government, in its Law Number 11 of 2008 on Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE), intended to address cyberspace issues including hoax and cybercrime. Yet the policy implementation has become contrary to its design.

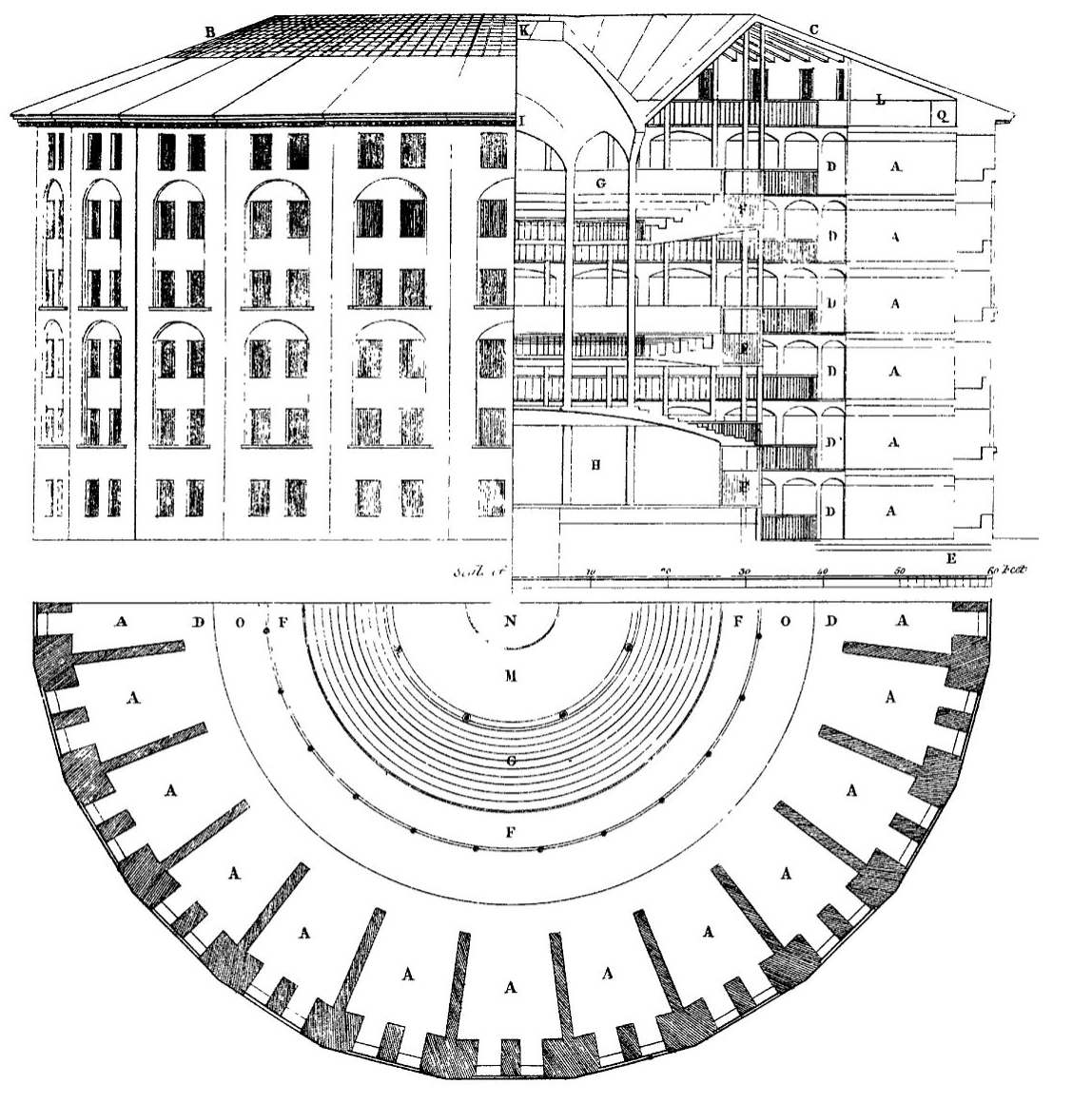

In the 18th century, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham provided the idea of the Panopticon, a system of control in which a single guard placed at the centre of a circular prison can oversee all of its inmates simultaneously because they do not know when they are being watched. The Panopticon concept can be applied to the internet, where democracy could erode as everyone online is theoretically being watched by the state.

Relating to Bentham’s Panopticon, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes articulated the concept of a Leviathan in his 1651 book of the same name. A metaphor for individuals relinquishing authority to enforce natural rules, Hobbes believed social order could not exist without the intervention of a powerful state or entity, otherwise we would fall into anarchy.

The internet in a Hobbesian sense exists as a state of nature in which we are all equal by our natural right. Internet users like to think they are free while roaming cyberspace, but this is far from the truth. In combination with Bentham’s Panopticon, users are being watched under the guise of governments regulating the internet.

Southeast Asia also consistently walks the line between internet freedom and Orwell’s all-seeing Big Brother state. The 2021 edition of the annual Freedom House report, Freedom on the Net, shows none of the Southeast Asian countries was labelled as ‘free.’ The Philippines scored the highest amongst its regional neighbours with a score of 65 out of 100. Myanmar, as a result of a February coup in which a military junta took over the government, drastically declined in internet freedom.

The Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network reported 786 legal violations in Indonesia’s cyber realm from 2016 to 2020, with 88% of offenders being incarcerated for defamation. Indonesian president Joko Widodo has solicited the nation’s House of Representatives to revise the ITE law, for what he termed as the sake of justice.

Thailand charged 100 people in 2020 and 2021 with violations of lèse-majesté law, which forbids defaming or insulting the royal family. The majority of the charges stemmed from online statements.

In Cambodia, the directors of two news websites, Rithysen and TVFB, received jail sentences in 2020 after their reporting was judged by the government to be “incitement to provoke turmoil and impair social security.”

We can gauge the cybersecurity commitment level of a country through the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI). The index is predicated on five pillars: legal, technical, organisational, capacity development and cooperation. The higher the score, the more committed a country is to cybersecurity.

The 2020 index report posits Singapore with the highest cybersecurity commitment among ASEAN member states with an overall score of 98.52, followed by Malaysia (98.06), Indonesia (94.88), Vietnam (94.55), Thailand (86.5), the Philippines (77), Brunei Darussalam (56.07), Myanmar (36.41), Lao P.D.R (20.34), Cambodia (19.12) and Timor Leste (4.26).

Although several obtained high scores, cybercrimes are still menacing Southeast Asian countries, including Singapore, the nation with the highest score.

Cybercrime was the source of up to 43% of overall crime in Singapore in 2020 with 16,117 cases, up from 9,349 cases in 2019. This included a data trade by hackers who stole the details of 400,000 Singaporean Fullerton Health customers.

Malaysia’s cybercrime rose by 838 cases, 82.5%, in 2020, spiking from 459 cases in 2019, according to data firm CTI Resources. The most glaring examples included the alleged sale in September 2021 of the details of 4 million Malaysians from myIDENTITY, an online service through which personal information can be shared with Malaysian government agencies.

Two cases in 2021 highlighted the low data security in Indonesia. Information from the Indonesian Child Protection Commission database was leaked, while the National Malware Centre hosted by the country’s National Cyber and Encryption Agency (BSSN) was infiltrated by Brazilian hackers. The irony of hacking the agency intended to avert and spot cyberattacks should be obvious.

Not only has personal data become susceptible to leaks, but in several cases personal data has been traded online. President Widodo’s vaccination certificate, including his personal details, was leaked from an app and spread on social media.

Beyond cyberlaw, data privacy also has become a significant concern in Southeast Asia.

ASEAN states have agreed to adopt the group’s Framework on Personal Data Protection. The framework aims to ensure accuracy, security safeguards, access and correction, retention of data and accountability.

While ASEAN states committed to the framework in 2016, most of the organisation’s members have not fully implemented the guidelines.

Among the ten ASEAN states, those that have implemented data privacy laws include the Philippines (Data Privacy Act of 2012), Malaysia (Personal Data Protection Act of 2010), Singapore (Personal Data Protection Act of 2012 ) and Thailand (Personal Data Protection Act of 2019).

Indonesia is still grappling with the draft of a Protection of Private Personal Data bill, while Vietnam does not have any comprehensive data privacy regulation.

Southeast Asia does not need regulation to protect digital freedom and personal data. The size and scope of the internet is already something of a Leviathan.

The internet, once boundless, is now bound by service providers enforcing a digital border where governments try to govern the digital world. In some cases, this power has transferred from centralised governments to private intermediaries, but regardless of the source of enforcement, the internet has become subject to control.

On the other hand of this online philosophical debate we have the Scottish philosopher and economist, Adam Smith. Smith posited the notion of the ‘invisible hand,’ a metaphor for the hidden forces driving the free market economy, serving the best interests of society through individual self-interest and freedom of production and consumption.

Freddie Phillips/ Flickr

The invisible hand metaphor also applies to cyberspace, which has allowed for increased interconnection that encourages mutually beneficial exchange. We are far more connected with the people around the world through cyberspace and therefore our actions and the rules we set out for ourselves in the cyber realm are fully regulated by user interactions.

The Adam Smith Institute in London has said the existence of too many government regulations might restrict individual freedom of speech. Statements and posts might be corrupted and used against individuals. They also state that “growing calls to regulate the internet risk undermining progress and threaten the future of the internet.”

What allowed cyberspace to flourish to the point it does now is the limitless exploration of ideas that users obtain through the increased online interconnectedness. This exploration of ideas has its roots in the notion of free speech.

Free speech is a pivotal part of freedom on the internet and the reason why we consider cyberspace the ‘last bastion of freedom.’ The problem lies with the existence of regulations hindering what we can say. Simply expressing online opinions deemed incorrect by authorities can lead to defamation charges.

A healthy internet would have a balance between free speech and moderation. Platforms should be given authority to regulate objectionable or unlawful content while allowing a free exchange of ideas. The internet exists as a place of growth and too many restrictions might stunt its development.

On one hand, the future will shape two-sided roles for government policy in cyberspace, whether as a Leviathan to control anarchy or an invisible hand to guide anarchy toward greater fortune than misfortune. On the other hand, as the internet has become home to roughly 400 million Southeast Asia netizens, individual freedom and data protections should remain important considerations.

ASEAN member states should address the region’s lack of cybersecurity and data privacy policies. In places where policies have been enacted, those nations should stick to laws hinged on the ASEAN framework. Insufficient data protection will inevitably beget catastrophe, while legal ambiguity serves as a potential menace to activities within the digital space.

Nations urgently need to amplify cybersecurity policies while digital infrastructure building capacity and online security. These actions require a solemn commitment and collaboration from governments, policy makers, cybersecurity experts and academia. Cyberspace should be granted room for growth, while at the same time online platforms have enough regulation to prevent harm to their users.

Aufarizqi Imaduddin and Albert Jehoshua Rapha are research assistant interns at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Indonesia.

This story was updated on 17 January 2022 to ASEAN to clarify internet user figures.