In 1999, a group of psychologists from the University of Leicester, UK, took over the tannoy system of an unassuming, suburban supermarket for a two-week period. On alternate days they played French and German music, and counted how many bottles of French- and German-branded wine were sold.

After crunching the numbers, they discovered that on the days French music was playing, French wine outsold the German bottles by a ratio of five to one. On the days that German music was playing, German wine outsold the French selection. Most shoppers had not even been aware that specific music was playing. It was their subconscious that led to their purchases. It was pure consumer psychology.

The history of consumer psychology is long and complex, but one can trace its early manifestations to an Easter parade held in New York City in 1929. As bands and revellers marched through the Big Apple, a dozen or so women stood on a busy sidewalk, smoking cigarettes. This may seem innocuous today, but at the time it was a taboo act. Women were only supposed to smoke within the confines of their homes.

A number of photographers were on hand to snap the women in this ‘indecent’ act, and the images appeared the next day in newspapers across the US. The women, emboldened, said they were not smoking cigarettes but “torches of freedom” – it was a feminist act. The New York Times went with the headline: “Group of Girls Puff at Cigarettes as a Gesture of ‘Freedom’”. The impact was startling. In 1923, less than 5% of cigarettes sold in the US were purchased by women. By 1935, this had risen to 18%.

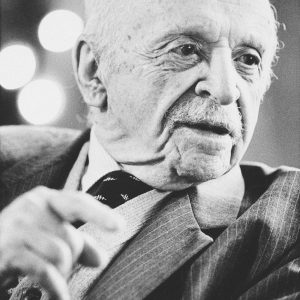

This was, however, no grassroots act but a well-crafted publicity campaign formulated by Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, and the so-called ‘father of public relations’. The Austrian-American had been hired by the American Tobacco Company to promote female smoking. The event had been his creation. He paid female models to smoke and the photographers to capture the act on film. He then sent the photographs to the media. He was carefully using the growing consciousness of increasing rights for women and female expression in order to emotionally change public opinion and habits.

In 1928, Bernays published his seminal book, Propaganda.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government,” he wrote. “In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons… who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.”

Bernays’s beliefs in how to manipulate the masses were rooted in the ideas of his uncle, Freud, whose work popularised the idea that people are governed subconscious and irrational thoughts. Bernays pioneered the idea that a few powerful people could psychologically manipulate and tap into the values of the masses – an integral part of modern-day consumer psychology.

It was another Austrian-American and adherent of Freud who turned these ideas to the world of advertising: Ernest Dichter. He understood the irrational and emotional ways people act as consumers.

“What people actually spend their money on in most instances are psychological differences, illusory brand images,” he wrote in his 1960 book, The Strategy of Desire. “You would be amazed to find how often we mislead ourselves, regardless of how smart we think we are, when we attempt to explain why we are behaving the way we do.”

Between the 1930s and 1960s, Dichter was hired by some of the world’s largest corporations to take over the advertising campaigns for failing products. One of his first jobs was with the Compton Advertising Agency, helping it to promote a brand of ivory soap that was not selling well. Instead of using standard questionnaires, which merely asked the public why they bought certain brands of soap, he turned to psychoanalysis as a way of understanding consumer behaviour.

According to a 2011 profile of Dichter’s lifework, published in the Economist, through extended interviews – that verged on therapy – he discovered that “bathing was a ritual that afforded rare moments of personal indulgence, particularly before a romantic date… He discerned an erotic element to bathing, observing that ‘one of the few occasions when the puritanical American [is] allowed to caress himself or herself [is] while applying soap’.”

As to the question of why a consumer purchased one brand of soap instead of another, Dichter reasoned that it was because of the ‘personality’ of the soap. A brand of soap could be old and conservative, or young and sexy. “Dichter understood that every product has an image, even a ‘soul’, and is bought not merely for the purpose it serves but for the values it seems to embody. Our possessions are extensions of our own personalities, which serve as a ‘kind of mirror which reflects our own image’,” the Economist article added.

Time magazine once described Dichter as “the first to apply to advertising the really scientific psychology” that understood peoples’ “hidden desires and urges”.

Today, consumer psychology is so ubiquitous that few shoppers or consumers will ever realise that their desires are carefully being tugged by the emotional strings of academics and theoreticians.

Next time you go to the supermarket, take a moment to think about why certain products are placed on certain shelves (eye-level display for expensive goods, while the cheaper goes lower down) and why you decide to purchase one brand of soap or shampoo over another.