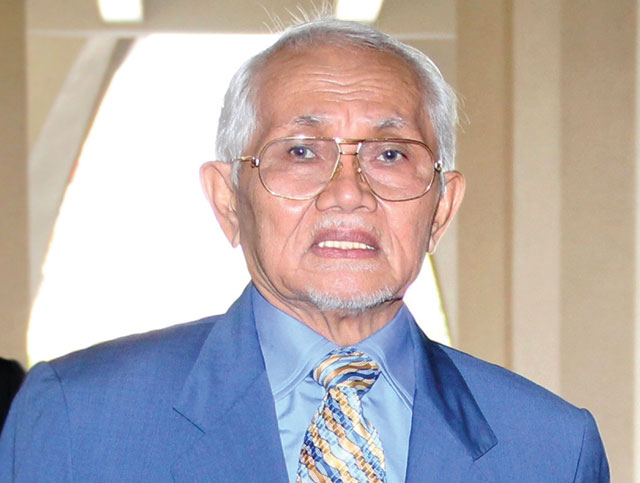

Land grabs, rampant deforestation and rumoured multibillion-dollar fortunes have been the hallmark of Taib Mahmud’s tenure as chief minister of Sarawak.

By Daniel Besant

The resplendently orange-beaked rhinoceros hornbill – Sarawak’s state bird – cuts quite a dash. However, if the trends of the past few decades continue, there will be no trees left for these birds to gather in.

One of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo, less than 5% of Sarawak’s area is left covered in forest, with the vast majority ofdestruction occurring during the controversial leadership of 77-year-old Taib Mahmud.

On February 12, Taib, as he is known, formally handed in his resignation as chief minister to the state legislature, ending 33 years in the post. He also concurrently held key positions as minister of finance, minister of resource planning and minister of environment. Adenan Satem, a 70-year-old former brother-in-law of Taib, succeeded him in all positions. Taib was not headed for retirement, however. He immediately became Sarawak’s governor – a move that has raised more than a few eyebrows.

“Taib is a completely inappropriate figure to act as governor,” said Alex Helan of environmental NGO Global Witness. “There is a significant amount of evidence that suggests he has abused his position of public office to enrich himself, his family and his associates.”

Lukas Straumann, executive director of the environmental conservation NGO Bruno Manser Fund (BMF), is unequivocal in his criticism of Taib’s legacy. “Taib Mahmud will be remembered as the chief minister who abused his public office to make himself and his family members billionaires by cutting down the Borneo rainforest and grabbing the indigenous communities’ lands,” he said.

Southeast Asia Globe emails to figures and companies connected to Taib went unanswered.

In March last year, Global Witness released a film called Inside Malaysia’s Shadow State that revealed how Taib’s network operated to circumvent laws and accumulate cash.

In the film, a representative of one of Sarawak’s biggest timber tycoons indicated that Taib would be likely to receive a kickback for the issuing of a plantation licence. A senior government official and a timber industry executive in Sarawak made similar claims.

The film also showed how Taib’s family was sold land via the Ministry of Resource Planning and Environment (then headed by Taib) for knockdown prices. Those family members then profited handsomely by selling the land for significant sums.

One of the biggest criticisms of Taib’s rule has been his alleged siphoning of money that could have gone to Malaysia’s state coffers to be spent on legitimate projects that would benefit the Malaysian people. In the report Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2002-2011 by research and advocacy organisation Global Financial Integrity, Malaysia ranked fourth in a list of countries that had the highest illegal financial outflows with an eye-watering total of $370 billion.

Also in the Global Witness film, a company owned by Taib’s first cousins – including a sister-in-law of the Malaysian prime minister and a Malaysian MP for Taib’s own political party, the Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu – was offered for sale via a proposed illegal transaction. This transaction would have been made in Singapore, thereby evading Malaysian tax.

Taib’s official chief minister’s salary was $194,000 per year. However, in 2012, the BMF estimated his fortune to be $15 billion. Speaking to rural voters in 2010, Taib said: “I have more money than I can ever spend.” Some of that money has been spent on a succession of Rolls-Royce cars, along with a ring sporting a walnut-sized ruby, not to mention an impressive international property portfolio.

In February, BMF revealed Taib had raised $16.9m from one of his properties in San Francisco. The BMF said that the US-registered company Sakti, controlled by Taib through a secret agreement with his closest family members, owned the building. Documents released by a whistleblower back in 2010 showed that Taib’s two brothers, Onn and Arip, and three of his children hold 50% of Sakti’s shares “in trust of Abdul Taib Mahmud”.

According to a 2010 census, Sarawak had a population of 2.4 million. In 2009, official statistics put the level of poverty at 5.9%, a figure that dropped to 2.4% in 2012. Sarawak State assemblyman Baru Bian cast doubt on these figures in February last year.

“While I would dearly like to believe these statistics, my observations during my trips in rural areas and in the interior of Sarawak give me reason to doubt the accuracy of this figure,” he said.

The assemblyman pointed to the poor levels of education above primary level for the indigenous people of Sarawak and linked that to a low standard of living.

“In Sarawak… the indigenous people, with only primary education or a lack of formal education, are relegated to jobs at the bottom end of the occupational hierarchy,” Bian said. “The Labour Force Survey Report Malaysia 2010 shows that Sarawak has the second highest number of workers in the labour force with no formal education. That is 94,000 workers, which accounts for 22.6% of the national total.”

The BMF’s Straumann believes things could change in Sarawak. “The hope is there that things might improve,” he said. “But a lot will depend on if Adenan can manage to prevent Taib from meddling in his affairs.”

Reducing his family’s influence must be Taib’s priority, said Bridget Welsh, associate professor of political science at Singapore Management University. Although the governorship is, on paper, a ceremonial role, she feels that Taib could help by “reducing his family’s direct and indirect role in the economy, building a younger leadership for the state, and maintaining the integrity of Sarawak vis-à-vis Peninsular Malaysia”.

Despite his long-standing hold over affairs in Sarawak, the situation is changing. “For Sarawakians, the most shocking revelation [in the film] was the disdain with which Taib’s cousins talked about indigenous communities, who they saw merely as impediments to their plans for self-enrichment,” said Helan. “The film was dubbed ‘squattergate’ and led to protests in [the state capital] Kuching and a court case against Taib’s cousins.”

Welsh agrees that change is in the air. “The time for new ideas is pressing and changes are coming in Sarawak as a product of globalisation and growth,” she said. “The new leadership cannot take Sarawakians and their support for granted.”

Meanwhile, the forest destruction continues. Palm oil plantations are fast superseding jungle in Sarawak’s interior. “Recent independent satellite analysis by Google and others shows Malaysia’s deforestation rate is three times higher than it has been reporting to the United Nations,” said Helan. “Malaysia, in fact, has the highest rate of deforestation in the world.”

On Sarawak, the forest destruction happens in two phases: Industrial-scale logging ruins forests until they are no longer commercially valuable for timber; they are then cleared to make way for plantations such as oil palm.

Besides plantations, Sarawak has plans for a number of hydropower dams. These dams will further reduce forest cover and displace indigenous communities. The dams are one part of plans to provide power for proposed large-scale projects such as an aluminium smelter; they are also alleged to be magnets for corruption.

“These plans are mainly serving the interests of the Taib family, who hold a monopoly over cement and steel production in Sarawak,” Straumann said. “These plans are neither economically nor environmentally sustainable, and we think they are mainly corruption-driven.”

With all this environmental destruction, it is fortunate the rhinoceros hornbill can live for up to 90 years in captivity. In Sarawak, captivity may soon be the only place it can live. Taib seems unconcerned. In his outgoing speech as chief minister he lambasted “malicious” NGOs, painted a bright future for all of Sarawak’s inhabitants, and was adamant that “honesty has been my leadership principle”.

***

In 2012, a report entitled The Taib Timber Mafia was released by the Bruno Manser Fund, which profiled Taib Mahmud and his relatives. Here is a look at three key members of the family.

Mahmud Abu Bekir Taib

With an estimated fortune of $1.5 billion, Taib Mahmud’s eldest son is a major figure in Sarawak’s property, construction and energy sectors. Between 2009 and 2011 he was handed more than 70,000 hectares of land for no payment. Speculation is rife that he will one day enter politics and eventually become chief minister of Sarawak.

Hanifah Hajar Taib-Alsree

Taib’s youngest child and the director of 16 companies in Sarawak wields great influence over the state’s press as director of a radio station and of a newspaper. She is a major shareholder in the state’s biggest company, Cahya Mata Sarawak Berhad, which is widely regarded as having a monopoly on construction materials including cement. Her fortune is estimated at $400m.

Onn bin Mahmud

Taib’s brother has a net worth estimated at $2 billion. Although he is the director of 11 Malaysian companies and a shareholder in another 23, his main source of wealth comes from his complete control of all timber exports from Sarawak. In 2007, an investigation by Japanese tax authorities found that tens of millions of dollars had been paid in kickbacks by Japanese companies to outfits owned and controlled by Onn.

Keep reading:

“The wood for the trees” – Despite community efforts to combat illegal logging, Cambodia’s forests continue to be pillaged at an alarming rate, while the government’s promises are frequently exposed as empty