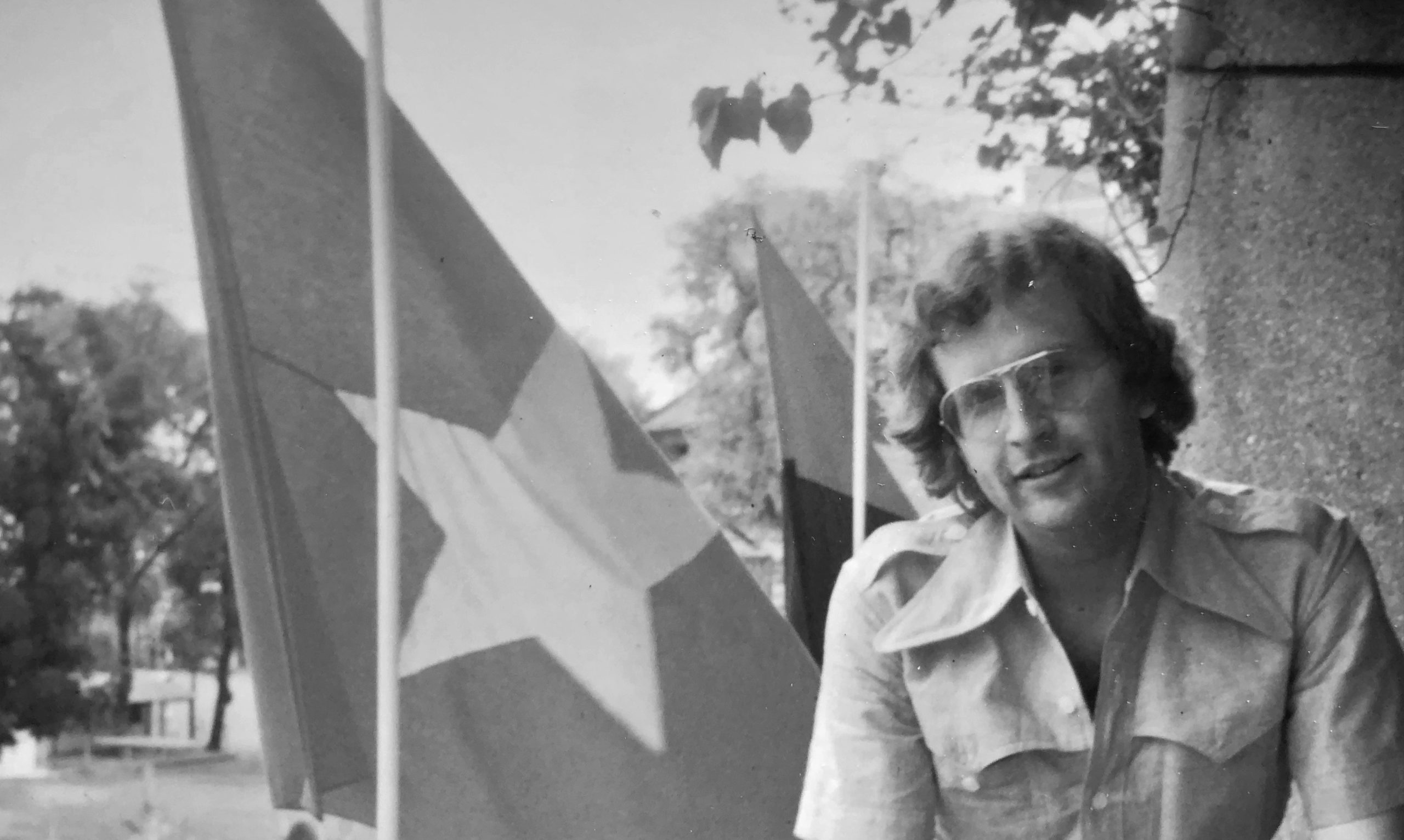

The following is adapted from Chapter 18: Giải Phóng (Liberated) of The Last Helicopter: Two lives in Indochina, a book by Jim Laurie. Laurie and photojournalist colleague Neil Davis working for NBC News were the only American television network staff reporters to remain behind in Saigon after the US Embassy led evacuation of April 29-30, 1975.

Wednesday morning, April 30, 1975. I was running late. The sun rose shortly before 6am. Saigoners always get out at dawn to catch the fresh air before the heat becomes oppressive. This morning, I wanted to pick up where I had left off the day before – in front of the US Embassy.

I ran downstairs at the Caravelle Hotel to meet my photojournalist colleague, Neil Davis. I found Neil relaxed, casually sipping his ca phe den, rich black Central Highlands coffee. He spread more pineapple jam on his morning croissants.

“No worries, mate. … Relax. Embassy’s not far.”

As we walked the half mile to the embassy, I noticed Saigon had taken on a slightly different feel from the night before. Whatever limited law and order prevailed in the city had disappeared. We heard a few scattered rounds of rifle fire. Somebody tried to keep order.

The gates secured by US Marines the night before stood wide open. As far as I could see, the embassy was abandoned. Thousands of Vietnamese streamed in and out of the compound, looting anything they could find, anything that was not fastened down. They carted off air conditioners, light fixtures, chairs and desks, files, and file cabinets. A young woman rode on the back of a Honda motorbike clutching yellow sofa cushions in one hand and an electric fan in the other.

There were some angry faces but most simply displayed the determination of opportunism. Perhaps, I thought, they were just trying to get back at the Americans, who had been here so long and now were cutting and running, deserting them.

I looked at the rooftop helipad. Not everyone had left the embassy. I could just barely make out the silhouettes in the early morning light of what looked like uniformed US Marines, M-16s at the ready.

From the east a giant helicopter flew in at low altitude and set down on the roof. Neil raised his camera to the sky and captured the final helicopter removing the last marines from the embassy roof. The chopper quickly gained altitude, heading east to the aircraft carriers in the South China Sea.

I looked at my watch: 8am. We had witnessed the end of the American embassy evacuation.

In front of the building, I was besieged by desperate Vietnamese, some who showed me identification cards proving they had been employed by United States government agencies.

A woman in a floppy white hat with concern embedded on her face pleaded with me. “I worked for USAID. My family and I need to get out. Can you help us?”

I explained I could not do anything. The last helicopters had gone and I was remaining in Saigon. She looked at me in desperate disbelief.

A little after 9:30am, I began filing accounts of the morning for NBC radio as the city awaited the arrival of the Vietnamese communists.

NBC television in New York booked a primetime network news special, so I kept a circuit to New York up while monitoring Saigon radio. My colleague Nguyen Van Anh translated the words of the retired general and the last president of the Republic of Vietnam, Duong Van Minh.

A little after ten, I got back on the circuit to New York. A short time later NBC’s John Chancellor went on the air.

“NBC News correspondent Jim Laurie is one of the few Americans left in Saigon. In the city President Duong Van Minh went on the radio and told the Viet Cong that his country would surrender unconditionally and that he had told its army to lay down its arms. Here from Saigon by radio hookup is Laurie’s report on the surrender.”

“In the words of General Minh, we are here to hand over the power of government to you in order to avoid bloodshed. It is a unilateral ceasefire and an unconditional surrender …”

The radio circuit remained up for another hour.

I ran outside and snapped a photo of a North Vietnamese tank rounding the corner near the Caravelle. I watched two tanks heading southeast toward the river. Another tank crew checked their maps on unfamiliar roads and moved toward the Presidential Palace, the headquarters of the “Saigon puppet regime”.

It was astounding. The war was over. My thoughts flashed back to 1970, riding those US tanks and helicopters in Cambodia, and to 1972 and a B-40 round in Quang Tri that nearly got me during the “Easter offensive.” Battles, deaths, misery over so many years. What was it all for? This was it. This is how it ends?

The voice circuit to New York went down at about 11:20am. I continued to file written updates, typing furiously on the NBC bureau telex machine.

“CALLING NBC NEWS NEW YORK 232346A OVER”

At about noon a message all in caps typed by an unknown operator at the Saigon Post and Telegraph building clattered across the telex. The keys stuck as the notice went out.

SGN TLX 18

VERY SORRY

AS PER SENTEL SAIGON

WE HV TO STOP THE TRANSMITTEEEEE TRANSMISSION NOW AND WE ARE STANDING BY THE NEW ORDER+ TKS BIBI +.

Communications were cut immediately. They were not restored for one week. The new order was in charge.

Leaving the embassy area, Neil Davis positioned himself at the Presidential Palace.

At noon, his viewfinder caught one of the wrought-iron gates of the palace. He captured Tank Number 843 smashing through the palace gate.

At an underground bunker about 20 miles north of Saigon, General Van Tien Dung got a radio message that the palace had been captured. He radioed Hanoi. General Dung told me in Hanoi many years later, “A cheer went up in the bunker. We were crying with joy and hugging each other. Our great spring victory was at last ours.”

I rejoined Neil late in the afternoon for a final combat operation, certainly one of the more unusual for either of us in all our years covering the war. This time we accompanied communist forces, the young men we came to call giai phong bo doi or “liberation foot soldiers.”

The giai phong bo doi began a mopping-up operation. They crept slowly forward, knowing they had all the time in the world. They didn’t seem to mind if we tagged along. “Just keep your head down,” Neil reminded me as I followed behind.

About forty or so armed South Vietnamese troops defying President Minh’s surrender orders hid out near Ho Con Rua (Turtle Monument), not far from the palace.

Neil and I followed a few feet behind the Hanoi soldiers. We heard scattered rifle fire from just behind a thick growth of trees. I ducked. Neil kept filming. The liberation troops held their fire. They moved forward, surrounding the South Vietnamese holdouts. They shouted out the equivalent of that old Wild West command: “Surrender or else! Come out with your hands up!”

About an hour later, as darkness approached, our mission with the giai phong bo doi ended. The “Saigon puppet” troops surrendered.

The early days of May seemed almost sleepy. Small groups of bo doi gathered around the city center. Clusters of Vietnamese civilians – led by young students – came out to talk to the boys from Hanoi. These hardened young soldiers seemed naive, rather shy country boys from the north, awed by Saigon and not sure what to make of it all.

I walked up and down Tu Do Street chatting with people. They greeted “giai phong” with some apprehension but mostly with smiles of relief. Relief, because the city had been spared heavy fighting.

On May 2, we drove to Cholon, the Chinese sector of the city that was always the center of new enterprise. We discovered a small factory churning out flags while local merchants were painting signs for the new rulers’ propaganda campaign.

The signs read “Vi dan, cho dan, boi dan”, or Government – “For the people, of the people, by the people.” The words were credited to Ho Chi Minh as borrowed from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

As all communications have been severed, the fate of as many as eighty foreign journalists remaining behind in Saigon is not known at this time

On Monday, May 5, Neil and I were getting restless. We wanted something different. A drive out of the capital might give us a better sense of how Hanoi forces were consolidating their new rule. An absence of petrol made travel difficult.

I suggested we drive west – along Route 1 toward Cu Chi. I had Cambodia on my mind. I had heard Khmer refugees had begun to cross over in Vietnam. Soc Sinan, the woman I had left behind in Phnom Penh, had friends in Vietnam. Was it possible she might make it to the border?

Neil had other ideas, but eventually a roadblock on Route 1 thwarted our Cambodia plan. Instead we traveled to My Tho, gateway to the Mekong Delta. I was surprised that rural life seemed to be returning to normal. The only vestiges of war we saw, less than a week after the greetings of “giai phong,” was the litter of South Vietnamese Army uniforms shed by Saigon soldiers after surrender.

In Saigon, unlike our colleagues in Phnom Penh, we lived in comfort. Life returned to a surreal normality.

The black market off of Ham Nghia Street reopened. I saw bo doi wearing their colonial-style green pith helmets wandering around photographing each other. I stopped and helped a soldier from Hanoi take a photo. The soldiers marveled at the array of goods on offer in the black market. They examined carefully and laughed at toy AK-47 rifles.

Communications with the outside world remained cut.

With some amusement, Neil and I sat in Givral’s Café listening to BBC news on my shortwave radio. “As all communications have been severed, the fate of as many as eighty foreign journalists remaining behind in Saigon is not known at this time,” the BBC World Service newsreader pronounced in somber tones.

On May 8, the first face of the new rulers appeared.

We were invited to the Presidential Palace, now Doc Lap (Independence Palace), to a news conference chaired by General Tran Van Tra, head of the Saigon Military Region Management Committee. General Tra was a deputy to General Dung, the architect of Hanoi’s victory, and had a reputation as a frank, outspoken man. Unlike many in leadership, he was a southerner.

In May 1975, General Tra came to urge the cooperation of all and assure us that conditions in “reunified” Vietnam were returning to “normal.”

“The road to reconstruction,” Tra admitted, “will be long and difficult.”

He stressed an issue very much on the minds of many who feared the communist takeover – “bloodbath.”

For years, Americans had spread fear in South Vietnam of widespread executions if the communists came to power. Uncertainty fed frightening rumors. I met young girls who feared their painted artificial fingernails would be ripped out by police. Or they feared they’d be forced to marry war-wounded, disabled North Vietnamese soldiers. It didn’t help things when word spread of what was happening to the urban elite in next-door Cambodia.

General Tra denounced reports of “bloodbath” as “despicable slander.” He called on Vietnamese who had fled the country to return and help rebuild a unified Vietnam. “With the exception of a small number of ringleaders or reactionaries,” Tra told us, “most had nothing to fear from the Provisional Revolutionary Government.”

After the general’s first meeting with the media, communications that had been cut for the past week were suddenly restored.

I raced back to the NBC office from Doc Lap Palace only to be disappointed. While cable traffic returned, radio circuits remained blocked, making voice reports impossible. We also still had no way to get our television film out.

I cabled New York that the city was returning to conditions somewhat similar to those before the fall.

Soon John Chancellor began quoting me in brief “readers” on Nightly News. As intended by the new authorities, General Tra got a mention.

My stories also began to appear out of Hong Kong in the Far Eastern Economic Review. On May 23, the headline on my story about General Tra read “A Sense of Relief after the Bullets.” It pretty much summed up the atmosphere during those early days of May.

By mid-May, all Vietnamese and foreigners alike were asked to register with the new authorities. I presented my passport to a man named Phuong Nam of the Foreign Affairs Section of the Military Management Committee.

I was duly registered and received certificate number 131.

It was fortunate I registered with the authorities when I did. Two days later I would meet some “Saigon cowboys”, our name since the early ‘70s for the motorcycle-riding thieves who proved a constant menace in the cities of South Vietnam, coming out of nowhere to swoop down on unsuspecting pedestrians.

I was in a hurry to meet a friend at Brodard’s café. I wore my satchel bag carelessly over my left shoulder as I hurried down the sidewalk. Roaring down Tu Do Street came two men on motorbikes. My bag disappeared suddenly into a plume of exhaust fumes as the cowboys gunned it in the direction of the port. In the bag was my passport, gone in a flash nearly two weeks after the US Embassy had fled.

A day after I reported my loss to the military committee, Saigon radio announced a war on street crime. Warning against “reactionary elements” in Saigon, the radio reported that “liberation security forces” were responding swiftly to an attack by thieves on an American television correspondent. According to the broadcast, these forces “apprehended the thief and shot him dead on the spot.” The broadcast sent a clear message. But as far as I knew, no one had been shot and I never got my passport back.

In the end, the French Embassy came to my rescue. Consul Jean Grosboillet could not have been more accommodating. On May 16, he presented me with new travel documents. I would travel on French “laissez-passer No. 318/75.”

We delay the start of the Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson to bring you the following NBC News Special Report – Communist Saigon

The month of May marked a series of important celebrations for “unified” Vietnam’s new rulers. On May 7, Hanoi marked the anniversary of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. On May 19 the Vietnamese observed Ho Chi Minh’s birthday and decided to rename Saigon after him. The name change became official in early 1976.

On May 15, the new rulers organized a victory parade, for which French, Russian, and Chinese journalists arrived from Hanoi. A large group of Vietnamese Party leaders also flew in, including both northern and southern cadre.

A large banner read in Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh’s words: “Nothing is more precious than freedom and independence.”

A few days after the big celebration, Phuong Nam from the Foreign Affairs Section called me in to give me a choice. I could leave Saigon for Vientiane, Laos with our more than 20 days’ worth of unexposed news film to process and air on NBC, or stay on a bit longer and not get the film out.

There was no real choice, so while my colleague Neil Davis remained in the city, I would board a special plane to Vientiane and then make my way to Hong Kong carrying three giant onion skin sacks containing his film. The Military Management Committee made all the arrangements.

On Saturday, May 24, I packed my bags and said goodbye to my Vietnamese and Cambodian friends who lived in Saigon. On Monday, May 26, from Hong Kong a special TV program aired on NBC. The announcer read: “We delay the start of the Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson to bring you the following NBC News Special Report – Communist Saigon.”

Looking back at my time in April and May 1975 in Indochina, the stark contrasts between Vietnam and Cambodia stand out.

I struggled with the news of the horrific evacuation of the Cambodian urban centers and the brutality of the Khmer communists. Yet in Vietnam, I observed an orderly takeover with fewer deaths than most expected.

Given the long war, shouldn’t South Vietnam’s communist takeover have been bloodier? I pondered the naivete of the Khmer and the cynicism (or realism) of the Vietnamese. I questioned why Khmer soldiers outside Phnom Penh fought on for five days after the American left them on their own.

However, in Vietnam, young soldiers pushed women and children out of the way to escape on planes and helicopters. Only a few South Vietnamese units put up a determined defense of their homeland. Within hours of the American departure, the war ended.

I was struck by a meeting Neil had with a young communist cadre who arrived in Saigon in mid-May from Hanoi.

“What I don’t understand,” he said, “is why the South didn’t fight harder for all their riches.” He pointed to a TV, a radio, and some furniture in his new Saigon apartment.

“Don’t you understand how destitute we were in North Vietnam?”