Open, close, open, close – not the instructions for a particularly fiddly front door, rather it is the pattern that schools in Cambodia have followed as the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic continues to throw the system into limbo, forcing educators to rip up the textbook and adapt like never before.

With the Ministry of Education closing schools across the country on November 30 in response to the now infamous November 28 cluster of Covid-19 cases, the education system in the Kingdom once again was forced to move from the school premises, back to bedrooms, kitchen tables and floors. A precaution against the rising number of Covid-19 community cases in the Kingdom, for teachers and students, it caps off a year of upheaval with remote learning tried and tested, exams delayed and social distancing introduced.

“It’s been very difficult with changes made to the year,” said Seng Hong, executive director of Cambodian NGO Education Partnership. “I think from now on, we need to be more flexible – the pandemic has shown that we cannot just stick to one rule about education.”

Schools first closed in Cambodia at the onset of the global pandemic in March. Remote learning was fast tracked and it was not until September 7 that schools nationwide could start to reopen their gates. But they were open for just a handful of months before being ordered to shut again on November 30, only after schools in Phnom Penh and Kandal closed for two weeks in response to the Hungarain Foreign Minister’s ill-fated visit, which spread the virus within the capital.

For educators in the Kingdom, the past nine months have seen them not just think outside the box – but reinvent the box, and their methods for teaching.

NGO Caring for Cambodia partners with a number of schools in Siem Reap province to provide educational opportunities to almost 7,000 students in the region. Its team worked to ensure any stops in physical teaching were adequately replaced, reopenings happened safely and that their schools were spotless.

“The reopening [in September] was hard because the students had to get used to a new system,” said Ung Savy, Caring for Cambodia’s country director. “We wanted to make sure that everyone was on the same page as we moved forward.”

Jamie Amelio, founder of Caring for Cambodia, explained to the Globe that teachers have had to go above and beyond to teach in completely new surroundings.

“It’s the teachers who have adapted immensely – they realised that if they wanted to teach they were going to have to figure out an innovative way to do it,” said Amelio. “And it’s such an inspiration to see teachers step up.”

Over the last couple of months, Amelio said that the unity and work ethic on display to ensure students could receive the same standard of education as before was remarkable.

“The camaraderie to make sure that schools were ready was nothing short of extraordinary,” Amelio said. “The teachers have probably had to dig deeper than ever before, to really try something new that no one prepared them for.”

Phoeun Phat, a science teacher at Aranh Sakor Cuthbert High, a Caring for Cambodia partner school, spoke to the Globe before the November 30 instruction to close, explaining how his classroom operated.

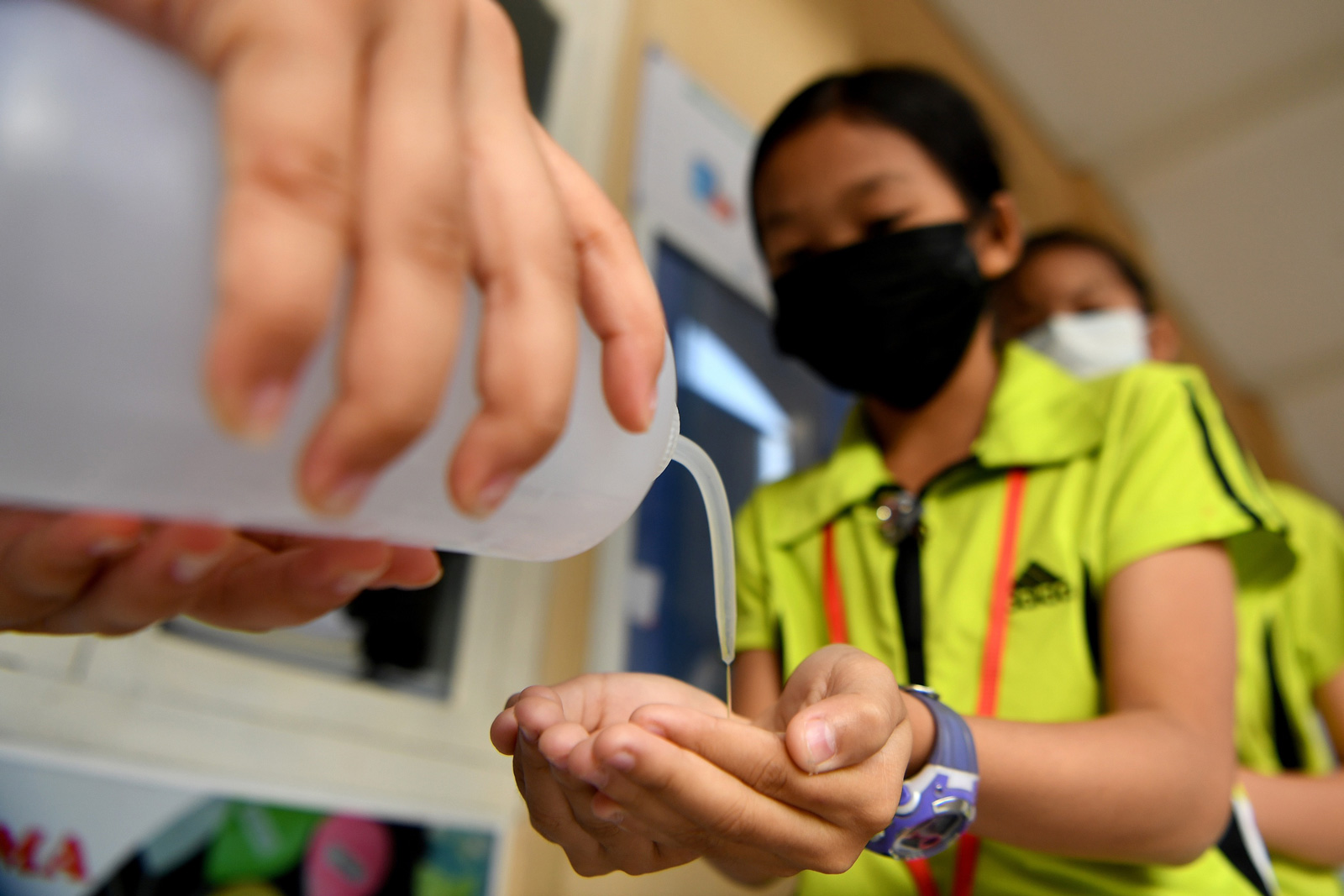

“The cleanliness of the environment outside and inside of the classroom was incredibly high,” said Phoeun. “Students were cleaning their hands regularly and we had to keep them two metres apart from one another. They weren’t allowed to ask each other questions face to face or come to meet their friend by their desk.”

Remote learning, like most places across the globe, has been the substitute for in-class teaching in Cambodia. It has cushioned the closures, ensuring that a total stop in education didn’t happen.

Kram Sok Channoeurn, country manager at Cambodian Children’s Fund (CCF) – a charity providing educational opportunities for Cambodia’s most impoverished children – explained that with the closure of schools, CCF will again have to utilise its remote learning framework.

“If anything positive has indeed come out of this situation, it’s a new emphasis on digital learning and an emphasis on doing that well,” Channoeurn said. “It was quite challenging at the beginning – however, despite this we arranged for distance learning while our schools have been forced to close.”

An emphasis on ICT and technology proficiency moving forward out of the pandemic is arguably one of the few, notable positive things to take from the crisis, with it allowing students to continue learning from home, mitigating the effects of school closures.

Caring for Cambodia has attempted to fill the void of physical teaching with its remote learning programme.

“It’s not what anyone has been used to, but with the pandemic affecting everyone – we had to change and roll out a new strategy for teaching,” said Ung.

Amelio explained the value of this period for students beyond the pandemic, as they acquire ICT skills that can take them into the workplace.

“It’s also for the future. If you can’t physically work somewhere, but you can use remote methods, you’ve got a chance at a future that you may have never had an opportunity for,” Amelio told the Globe. “Because the students’ entire paradigm has shifted, knowing how important these things are and how to utilise them has become important.”

However, Pitfalls with remote learning, which will become pressing issues once again with the closure of schools late last month, persist in Cambodia.

Most commonly, students are unable to access the internet or acquire the resources needed to work from home. This is most prevalent in rural areas of the Kingdom, where fixed internet access is uncommon, or among Cambodia’s most impoverished students – who simply cannot afford the costs associated with online teaching.

Caring for Cambodia is also hamstrung by the sheer scale of digital resources currently needed. They are able to provide for many students and teachers, but working in poorer communities in often rural settings, they are unable to provide for all. The organisation has taxed its modest inventory of laptops, many of them more than five years old, to distribute them to teachers who lack their own personal devices.

For educators, these factors meant it was a relief back in September when they returned to the classroom.

“When the students came back to class [at Aranh Sakor Cuthbert High] it was good to see,” said Phoeun. “It was better seeing the students able to understand the lesson inside the classroom, rather than through a computer screen.”

Studying at home – sometimes you have to go and find a place to get WiFi access … Sometimes you don’t understand the question – it’s a bit more difficult to ask a friend or a teacher

Lika is in year 12 at Aranh Sakor Cuthbert High School and due to take her national exams this month. The 17-year-old’s final year of schooling has been stop-start, with her having to prepare for her final year tests on an electronic device at home.

“Studying at home – sometimes you have to go and find a place to get WiFi access,” she said. “Sometimes you don’t understand the question – it’s a bit more difficult to ask a friend or a teacher.”

Lika’s mother, Sophal, explained that a parent also can’t provide the clarity a teacher can. “My daughter will say; ‘Mummy, I did not understand this lesson’,” said Sophal. “And in this department I cannot really help, so it is not a perfect situation.”

It’s also costly for the family, with many having to buy data packs to access the online resources. “We haven’t got an internet connection at home, so it’s a costly resource – ensuring we have enough to buy data for her [Lika] to access the teaching resources,” explained Sophal.

Children with learning disabilities often find it harder to learn remotely in a new environment, lacking the essential in-person support they receive from teachers and assistants, communicating instead via pixels. “Those children who have a disability or autism – they may find it harder to get an understanding of the new concept of remote learning,” said Hong.

The economic downturn – specifically the drain on the tourism sector in Cambodia – has also had a domino effect onto the education sector, specifically children dropping out to go into work and help their family to earn money.

“For many parents, they struggle to generate any income,” said Hong. “Many children have had to leave school to find work and help the family.”

In tourism-reliant Siem Reap, things are even more acute. Lika’s father works in the tourism industry – with no foreigners, his ability to earn for the family is severely impacted. “There is only now one person who can support the whole family,” said Sophal, Lika’s mother. “So we don’t have much money for the family.”

Amelio has been unable to travel as usual to Siem Reap and to Caring for Cambodia’s schools in the province due to the pandemic. She said that the hit to the city’s tourism sector is devastating. “What’s happened to Siem Reap is chilling,” said Amelio. “It’s an absolute disaster – it’s incredibly sad.”

Perhaps reinvigorated and eager to learn after months of being homebound, Ung told the Globe that the dropout rate of students after the reopening of schools in September was 3%, a comparatively low number. But the Caring for Cambodia country director observed that many didn’t return at all.

“The economic downturn has had a major effect on the area – some children are unable to return because they need to help their family generate income,” said Ung. “Our dropout rate is very low – which is good – but it is still sad for those children who have been unable to return.”

The grade 12 national exams will go ahead this month, despite the school closure order. While not the ideal environment to have a crack at the most important exam in the schooling calendar – steps have been taken to ensure those students taking it have been given as much support as possible.

But ultimately, as final exams approach, the school year ends and 2020 comes to a thankful close – one of the big losses faced by students, said Amelio, are the milestones that should be a cause for cherishment.

“Students normally can look forward to those milestones,” said Amelio, referring to their last day of school, the completion of the national exam and graduating. “It was cause for celebration and they’re not going to have that – they will have missed out on some really fun moments that they deserve.”

Amelio believes, however, that this generation of students will have come through an education far different from previous cohorts – an experience that has the potential to shape their characters and outlook on life.

“What’s happened this year has been extraordinary for these students, it will shape who they are and how they react to things later in life,” said Amelio. “They haven’t had control over what has come their way this year, but they’ve dealt with it amazingly.”

This article has been written in partnership with Caring for Cambodia, as a part of an ongoing series exploring education in Cambodia and the steps being made to bring hope to future generations. Find out more here.