After two days hiking through the rugged, steep mountains south of the East Timor capital Díli, Australian filmmaker and camera operator Sophie Barry arrived at one of the makeshift camps administered by rebel group Falintil.

Sitting in a small hut concealed by the dense foliage of the jungle trees, Sophie’s first meeting with Falintil’s leadership is one that she recalls with ease, shaking her head in incredulity as she speaks.

“I’ll never forget, in walked this guy with a massive afro and a massive gun in his fatigue, and then another one walked in and another,” remembered Sophie. “I just remember thinking: ‘you are kidding me!’ I’ve got no idea where I am, where I’m going, what I’m doing and with these people that I can’t even communicate with.”

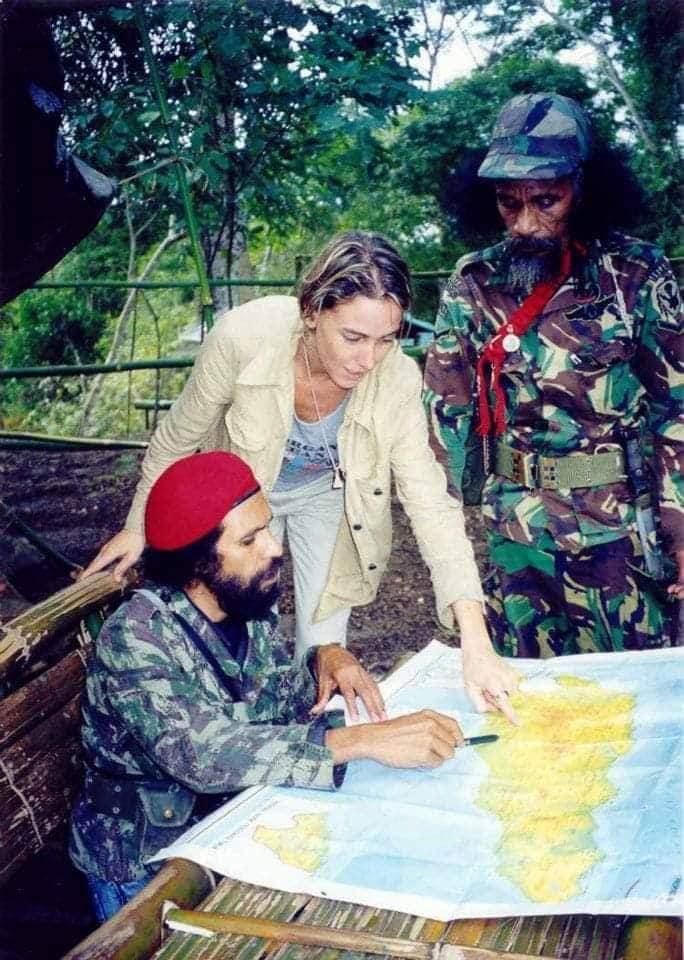

It was July 1998 and Sophie had been invited to accompany British photojournalist Philip Blenkinsop for a pivotal interview with the enigmatic leader of East Timor’s pro-independence guerrilla movement, Taur Matan Ruak. Then commander of the rebel faction, today prime minister of East Timor, the interview with Taur Matan Ruak, published in the now-defunct Far Eastern Economic Review, provided an international platform for the country’s independence movement, giving voice to the clandestine and long-persecuted group.

“We spent days walking through the mountains in the rain, in spider pits and with mountain goats walking along, it was a nightmare. But we finally got there and there was Taur Matan Ruak and all the leaders, there were more than four hundred people. It was just amazing,” said Sophie.

“[Taur Matan Ruak] was very friendly, kind and composed, yet he had a serious look that seemed to command respect from his soldiers. He understood our reason for being there and appreciated the journey we had made to interview him and tell part of the Falantil resistance story.”

The trip left a lasting impression on Sophie. She returned the following year asking her sister, fellow filmmaker and longtime collaborator Lyndal Barry, to come along. When they returned, East Timor was finally nearing a referendum that would free the country from a quarter of a century of Indonesian control and set it on a path towards independence, and the sisters wanted to document this firsthand.

Among a band of local and foreign journalists that would navigate the extreme brutality that defined the conflict, the Barry sisters were witness to the struggle and reforms that emerged during these pivotal years.

“From day one, when we first arrived in East Timor it was pretty violent. Within about an hour of being there, we had a gun at our heads by a militia guy,” Lyndal recounts, the pair speaking to the Globe over a video call from Thailand.

“At that point the [Indonesian] militias were kind of crazy and they were jumped up on amphetamines and I think it was just to terrorise journalists more.”

Despite the Indonesian government’s tight restrictions on entry, a large number of journalists had flocked to the country in the late 1990s. The sisters remember the number being close to one hundred, including both foreign and local journalists, but nearly all were stringently followed by minders documenting their every move.

“East Timor was known as the Indonesian military or TNI’s [Indonesian National Armed Forces] playground – an area which was tightly controlled by them,” the sisters remembered.

“There was active conflict between the Falantil and the Indonesian army during these years, and a strong international lobby for independence, therefore the Indonesian government did not want people to see it.”

While there were no illusions of safety for anyone in East Timor during the conflict-ridden years, journalists were targeted and Australians faced added risk. As talk of an independence referendum began to gain traction in the late 1990s, Australia became one of the most vocal countries in mounting pressure on Jakarta, sparking animosity among the pro-Indonesian militias.

“I remember some Indonesian army guys had drawn pictures on the wall of what they would do to Australian journalists like hanging them and shooting them and raping them. That was left on the wall of a place we were staying,” recounted Lyndal.

We couldn’t recognise the body at first because they had souvenired parts of his face and taken off his ears and cut off his mouth

Violent incidents involving other journalists also played into a general atmosphere of fear at the time. The murder of Dutch journalist Sander Thoenes, who had been working for the Financial Times in East Timor until he was shot and mutilated by the Indonesian army in September 1999, was one incident that shook the journalism community.

Sophie and Lyndal were two of the first people on the scene when his body was discovered in Díli.

“A Timorese came up to the hotel we were in and said there’s a dead body of a foreigner up the road. We couldn’t recognise the body at first because they had souvenired parts of his face and taken off his ears and cut off his mouth,” remembered Lyndal.

“The way I recognised him was we had bought the same cargo pants the day before.”

While devastating, it was sadly nothing new, with Thoenes’ murder resembling the tactics used by the Indonesian army over two decades earlier.

In November 1975, pro-independence group Fretilin, the political wing of Falintil, had unilaterally declared the country independent from Portugal. Nine days later, Indonesia responded by orchestrating an invasion and declaring East Timor an Indonesian province.

A month prior to the Indonesian invasion in October 1975, a group of five foreign journalists entered the country. Travelling from Díli to Balibo, a small town approximately 120 kilometres south of the capital, they were murdered by pro-Indonesian militias. Known as the Balibo Five, the nature of the attacks continued to loom over the country during the 1999 crisis.

“The Balibo Five is such a strong incident and image. The first time I went in it wasn’t part of my thinking, I didn’t have that fear, but I was probably naïve,” said Sophie.

East Timor remained under Indonesian occupation from 1975 until 1999. Over the quarter century, fear and violence gripped the streets as Falintil faced off against the Indonesian militias and, by the end, over 100,000 deaths were directly attributable to the occupation.

When Sophie and Lyndal arrived in the country on their first joint trip in July 1999, there was little effort to disguise or downplay the violence by either side. Dead bodies littered the streets and demonstrations broke out daily in urban centres. By August of that year, long-time Indonesian president Suharto, who had orchestrated the annexation of East Timor in 1975, had resigned. He was replaced by B.J. Habibie in a landmark election that saw Indonesia transition into an era of reform after decades of harsh dictatorship.

There was silence and then everyone was jumping and it was all happy and everyone was crying. It was five minutes of freedom, and then everything kicked off

Growing increasingly frustrated with the cost of containing the insurgency in East Timor and facing pressure from the UN and the international community to withdraw, Habibie set in motion a referendum that would allow the East Timorese to vote for greater autonomy under Indonesian control or full independence as a sovereign state. The referendum was held on August 30, 1999, with the results overwhelmingly in favour of independence as 78.5% voted against greater autonomy under Indonesian sovereignty.

“One of the highlights was in the sports centre behind the church [in Díli] when they announced the results. It still makes me want to cry,” said Sophie.

“We had a walkie talkie at the time and so we got the results directly. Then the priest read them out to the room. There was silence and then everyone was jumping and it was all happy and everyone was crying. It was five minutes of freedom, and then everything kicked off.”

Though the results were unambiguous, the aftermath of their announcement led to mass violence and killings across the country. For nearly two weeks, pro-Indonesian militias, armed with machetes and homemade guns, burned and looted buildings, destroying homes and forcing out foreign journalists in retribution of those who had supported independence.

“When we left [East Timor], we probably hadn’t slept for ten nights and we were exhausted. Eventually the Indonesian army came into our hotel and said ‘get on the back of the trucks, you’re going to the airport’,” said Lyndal.

Sophie and Lyndal boarded a plane to Jakarta. However, two weeks later in late September, eager to return, the sisters paid over $1,000 each for two plane tickets back into East Timor on a press flight. This time they remained in the country for nearly four years.

When they returned, Habibie had announced that Indonesia would be withdrawing troops and a peacekeeping mission led by Australia was being formed to assist with the transition. In documenting these sea changes, as well as the toll that decades of violence had taken on the country, Sophie and Lyndal continued to film and speak with people and soldiers across the country.

As the sisters continued to work on their 2001 documentary, The Long Road to Freedom, they witnessed a new wave of freedom and hope in East Timor after so many decades of mass violence and oppression. However, the shift was far from immediate.

While the conflict had subsided by the millenium and Indonesian troops were leaving, there was no effective government for several months. In October 1999, the administration of East Timor was taken over by the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET). UNTAET was active for nearly three years, overseeing the country’s first elections in 2001 and the establishment of an independent constitution in 2002. But the mission, coming into the country as outsiders, gradually lost its stature.

“To watch a whole legal and administrative system be put together in a year was really interesting and really difficult. For the first while, there was only one doctor in the whole country because most of the civil servants moved back to Indonesia,” remembered Lyndal.

“There was no effective government for some time, though the UN wouldn’t say that. But there was almost no law for several months and the UN went from being the heroes to the hated administration, but it was probably better for most than Indonesian rule.”

After several tumultuous years, the UN mission left East Timor in 2002. By then, the dust had settled and the country was entering a new era of independence, revelling in long sought after peace but still shaped by the bloody struggle of the previous decades.

“[Timorese] people had fought for so long and had been on their knees and subjugated so badly, then they finally got what they had fought for,” explained the sisters, speaking over each other at times as they were swept up reliving the memory.

“The fact that it had been such a long struggle made it even more amazing – for every generation, from the kids who hadn’t even seen it to the grandparents who’d lived through it all, it was all very emotional.”