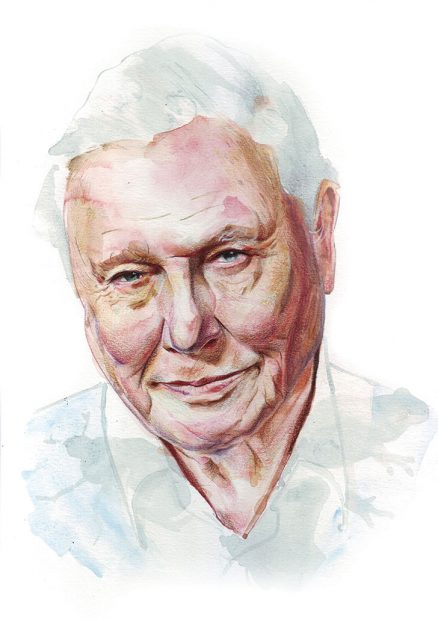

The private life of planet Earth: David Attenborough on the world's greatest challenge

To mark world Earth Day this month, we revisit our interview with the world’s most famous naturalist, David Attenborough, has captivated viewers with his wildlife documentaries for decades. Here, he gets serious about an issue close to his heart: climate change

Editor’s note: To commemorate Earth Day this month, we dug into our archive and found a 2016 interview with one of the most globally renowned figures in wildlife conservation and education, Sir David Attenborough. The British broadcaster, now 95, was honoured by the United Nations Environment Programme on 21 April with a ‘Champion of the Earth’ lifetime achievement award.

In the sightless silence of the sea, a nameless host is ablaze with light. Beneath the waves, luminous plankton burn like distant stars, hinting at hidden worlds. Transfixed in your living room, a familiar voice washes over you like the tide, and you begin to understand. Once again, Sir David Attenborough is showing you the light.

Since his first nature series, Zoo Quest, aired on the BBC in black-and-white in 1954, Attenborough has become the most influential and widely loved nature broadcaster in the world. Famous for his soft, lilting voice and boyish fascination with the wonders of wildlife, Attenborough – who celebrated his 90th birthday in May – continues to inspire generation after generation with breathtaking visions of the natural world. His latest film, Life That Glows, is a haunting glimpse into the twilight worlds of plants, insects and animals that burn with their own bioluminescent light.

But as the Earth’s population swells to breaking point and climate change continues at a pace almost unchallenged by the international community, finding light in the midst of darkness is not always so easy for the man who has become the unofficial face of the struggle to, quite literally, save the world.

When asked how he manages to remain positive in the face of global catastrophe, his normally animated features grow still.

“It’s difficult,” he says. “Not enough is being done, or can be done. There were steps made during [the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris], but enough to have a real effect? That is uncertain.”

A climate for change

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a man who never lost the childlike wonder of his early years, his faith is placed solely with those destined – or doomed – to inherit the Earth.

“It’s the next generation where I see hope,” he says. “Children right now, they are being exposed to the dangers of climate change and they are not overawed. They will have grown up with this and understand it’s a global issue that needs to be challenged head-on.”

With extreme weather conditions predicted to increase as climate change worsens, the consequences of inaction have become only too clear. Last year, as illegal slash-and-burn tactics employed by farmers in the palm oil and paper industries left Indonesia’s forests ablaze, emitting a toxic haze that smothered large swathes of Southeast Asia, horrified scientists estimated that the inferno could surpass the devastating 1997 fires that released as much as 2.57 gigatonnes of carbon emissions into the atmosphere – the equivalent of 40% of the world’s fossil fuel emissions each year.

Watching the blaze from on high, Attenborough did not hold back from pointing out the role of his own nation, the UK, in contributing to the devastation.

“You fly over Indonesian rainforests, burning and clearing for the production of palm oil and hear so many tuts and ‘isn’t that just awful’,” he says. “But we’re to be held accountable. Palm oil is in so many of the products we eat in Britain – we can’t do without it.

“It’s easy enough to say ‘ya-boo’ to the Indonesians, but we’re buying into it; it’s down to us.”

Saving the planet

Like much of the developing world, Southeast Asia is one of the regions where the effects of climate change will hit hardest. Struggling to match the economic growth of the developed world – historically responsible for an estimated two-thirds of the planet’s carbon emissions – Southeast Asian nations are in danger of finding themselves footing the bill for the excesses of their competitors. For Attenborough, though, this challenge may present an opportunity to lead the way in solving the problem of climate change.

“It’s all about research when it comes to developing countries,” he says. “Finding new ways of generating and storing power, power from renewable energies. If we adopt the appropriate research policies, we will be able to produce energy that is much cheaper than fossil fuels, than coal. There is your success – alternative resources and cheaper substitutes. If these are made cheaper for developing countries, surely that adds up to the greatest logic of all.”

It is this vision of a world united against climate change, perhaps, that helped secure Attenborough’s invitation to the White House last year. In a cosy interview with US President Barack Obama, the two men chatted about the early seeds of their love of the natural world – and their struggles to preserve it. When asked about the experience of meeting the most powerful man in the world, Attenborough was exuberant.

“[It was] hugely satisfying. To get a call asking would you not only like to come to the White House but to meet the president. And be interviewed by the president. My word,” he laughs. “I found him to be a sincere leader, genuinely concerned with the effects of climate change. As he explained, he grew up fascinated by the natural world.”

The mild-mannered presenter is less happy with his own government’s efforts in fighting climate change under recently resigned conservative Prime Minister David Cameron – though he points out that the populist nature of politics can make bipartisan action difficult.

“Of course we’re not doing enough,” he says. “And it’s a very difficult thing to do. If you’ve got a five-year mandate, when you’re elected you naturally want to do things that get you back into power. You want to say to the electorate: ‘This is what you wanted, so here it is; we did it.’ It’s quite hard to say: ‘There you are, we’ve taxed you for something that your grandchildren will be grateful for.’ That’s tricky.”

David Attenborough’s private life

Politicians aren’t the only ones struggling to manage public expectations. For Attenborough, one of the challenges of managing his celebrity is convincing a devoted audience that, when it comes to climate change, he doesn’t quite know it all.

“It’s an embarrassment in that sense,” he says with a laugh. “I’m on the television talking about it, so I understand, but if you really wanted to know important things, [from] an authority on climate change, you wouldn’t come to someone like me. You go to a climatologist. You go to a climate scientist.”

For Attenborough, though, the reality of climate change is not one he shrinks away from.

“The facts are indisputable,” he says. “Have humans any responsibility in this matter and are they the cause of it? Of course, we are completely to blame. The population has increased astonishingly in the past 50 years; it would be foolish to think there was no impact on the climate. Anybody can see that.”

After more than 60 years travelling the globe, Attenborough does not have a whole lot left to see. And for a man who has built a career journeying to places ranging from the rainforests of Africa to the icy wastes of the Arctic, the idea of relaxing on a beach in Bali holds little interest.

“I’m very happy to travel and do things, but to travel without a purpose is not something I would do,” he says. “I don’t like travel for its own sake. I like what you find as a consequence of travel.

“As you get older, you know, one knows what Venice is like,” he laughs. “Though I wouldn’t mind going back there – the food’s not bad.”