Wayland Blue volunteers as the director of research and evaluation with the Shade Tree Foundation in Mae Sot, Thailand which is focused on protecting and empowering Myanmar migrant families through counselling, education, and entrepreneurship training.

I first came to the town of Mae Sot on the Thai-Myanmar border 14 years ago as a young man travelling the world. I then moved back full-time in 2018 after leaving active duty in the US military to undertake humanitarian work for a Thai NGO called the Shade Tree Foundation, an organisation focusing on family protection and education in Mae Sot’s migrant community.

Mae Sot is the biggest border crossing for trade between Thailand and Myanmar. It is also where most migrant workers cross to find work in Thailand and is a few hours drive from the Mae La refugee camp, home to over 50,000 largely Karen refugees displaced by decades of civil war in Myanmar.

When I first came here it seemed unlike anywhere else in Thailand I had been, with its strong influence from the many Burmese migrants and refugees living here or passing through to escape conflict and instability. The sense of the town being at a crossroads for major events and people from all over the region drew me back permanently.

When February came, several colleagues and I expected Covid-19 to take a tragic toll in our area. Many migrants suffer from pre-existing illnesses like TB and HIV, and all of us suffering from extreme air pollution at the height of mainland Southeast Asia’s dry season, which is also the time for burning stubble in the fields to make way for new planting.

There was a growing sense of anxiety throughout the town as Thailand’s number of cases increased, movement restrictions began coming into effect, and local businesses closed down. No one knew what to expect and many feared the situation would rapidly deteriorate. I too was expecting the worst and stocked up on masks, gloves, and basic necessities.

As of writing, we have avoided local outbreaks largely thanks to early measures restricting travel and the closing of not only national but also provincial borders. However, these same measures also trapped thousands of Myanmar migrant workers from across our shared border, with severe consequences.

Many lost their jobs in manufacturing and the service sector as supply chains were disrupted and the lockdown took effect. For people already chronically insecure, vulnerable to exploitation in the form of human trafficking, and with some often relying on black market credit at exorbitant interest rates simply to pay for food, we expected the tragedy from the second-order economic effects to be even worse.

By mid-March, operating on the assumptions that 1.) the outbreak was going to be serious, especially in migrant communities with limited access to healthcare and inadequate sanitation facilities, and 2.) a significant number of people would soon be in life-threatening poverty with nowhere to go, we set about planning and executing an emergency response.

Taking Action

The fact most of our staff are from that community gave us immediate access. We identified that the best thing we could do would be to reach as many people as possible in the migrant community and get them aware of Covid-19 – what it was, how it spreads, and how to protect against it.

The language barrier meant this message would have to be shared face to face. However, we also knew we would have to follow strict sanitation and social distancing guidelines and prevent large gatherings.

The solution we settled on was simple. Go house to house and family to family in each community and provide quick, concise instructions on Covid-19 mitigation through hand washing, all while maintaining two metres distance and wearing facemasks. We threw in hand soap and face masks for each family we visited as well to make it worth their while.

We called the project Soap N Hope and quickly set about recruiting and training volunteers from the local Myanmar community to do the household engagements.

The newly formed team developed a script for the household visits that would keep each one under 10 minutes and emphasise the need to avoid prolonged contact. Meanwhile, our logistics team set about becoming the main purchaser of soap in Mae Sot, and our office staff began sewing facemasks.

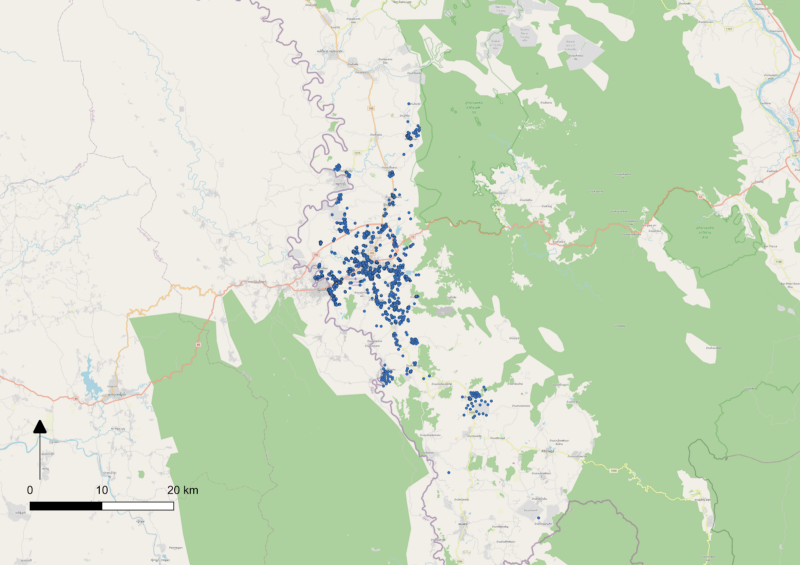

We started in late March with six field volunteers and grew to 16 in the following weeks. Averaging about 250 household visits a day, the teams reached over 5,000 households in the space of one month. The average estimated family size in the migrant community being five people, this translated to over 25,000 migrants. To my knowledge, this was possibly the largest outreach of its kind in the area.

Expanding The Effort

We were pleased with our efforts in what we called Phase 1 of Soap N Hope. We had hopefully prepared thousands of people to protect themselves and their families if the virus made it to Mae Sot. However, while health remained under control, we were beginning to see the effects of economic collapse and mass unemployment.

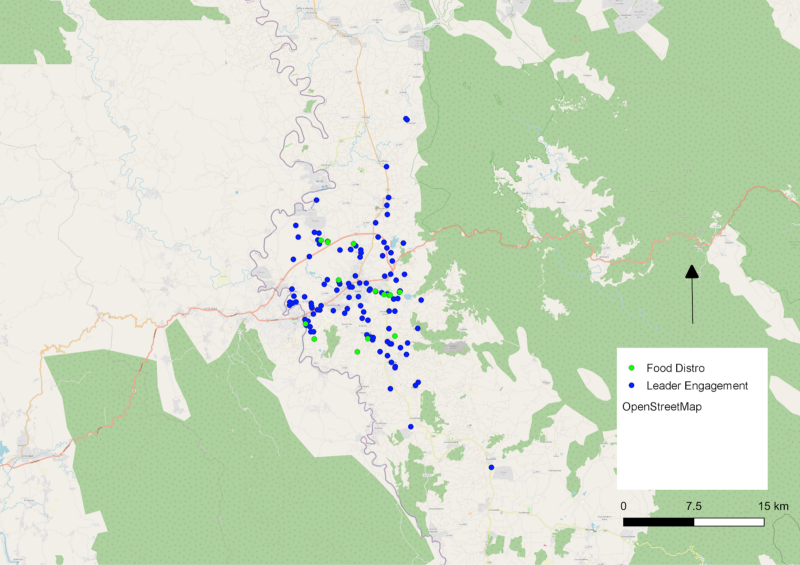

Throughout the first phase of Soap N Hope, we had been marking each household visit using Google’s My Maps app. I analysed the map to find clusters of households that indicated a stable community and marked these as areas for further investigation, giving us a rough idea of where to find community leaders to open lines of communication.

Driving on the rough and often steep roads the car overheated, forcing us to stop and use drinking water to cool the engine. I stressed and wondered if we would make it home, but my Burmese team members laughed – they are people who have overcome great adversity

Our Burmese volunteers developed a script for engaging the community leaders, asking what issues they were facing and providing our contact information. Beginning in late April the teams went to the points I had marked and searched – sometimes frustratingly, but always enthusiastically – for key contacts.

I was a driver and was impressed with their dedication and positive attitude working in the heat of the day – even when, on one occasion, the car broke down. Based on the map data collected I advised them on where to find community leaders, but my estimates were sometimes wrong.

I soon found out how wrong I could be as we searched in vain for what I thought was a remote community near the border. Driving on the rough and often steep roads the car overheated, forcing us to stop and use drinking water to cool the engine. I stressed and wondered if we would make it home, but my Burmese team members laughed – they are people who have overcome great adversity.

In the space of just over two weeks, the team managed to reach and contact over one hundred small migrant communities, ranging from factory dormitories to agricultural settlements and make a first introduction with the headman or, quite often, headwoman.

One day on driving duty I took some volunteers to visit a settlement in an agricultural area. When we got there the team asked to meet the community leader and were told to visit “grandma”. Grandma turned out to be the headwoman of a well organised village in the middle of sugarcane fields.

To both our surprise and relief, many of the communities were relatively well off. In the case of many factory workers, employers were providing food relief to hold the workers over until orders started coming in again, or until the border opened for migrants to return to Myanmar. Also, across the community, aid organisations, community groups and the local government were already providing food aid.

We suspected some communities would fall through the cracks, and ended up identifying a few dozen communities and households left out and facing a serious crisis – often single parent households or families with many children and no employment.

Local knowledge was critical for determining what went into food packages. Many migrant workers coming from Myanmar experienced the effects of the country’s long-running civil wars and know what it’s like to be displaced from their homes, on the run, and trying to make ends meet to stay alive. Some essential foods for lean times are rice, oil, chilli, and fishpaste – we focused on the rice and oil and added beans for protein and onions because they are popular in local cooking.

Soap N Hope Phase 2 drew to a close in mid-May, and now local agricultural work is picking up, factories are operating again, and many local restrictions are being relaxed.

The future here and everywhere remains uncertain. Covid-19 may still arrive, as many fear it will with the coming rainy season which is the normal time for outbreaks of respiratory disease in the region. The larger macroeconomic impact of lockdowns and disrupted global supply chains may yet mean disaster for the local manufacturing industry in which many migrants from Myanmar are employed.

As someone who lives here but still a cultural outsider, I was grateful to lend my skills in supporting the local community and inspired to see them looking out for those most in need. With limited resources and facing great uncertainty, many local people dedicated their efforts to help those less well off. In doing so I saw them confront uncertainty and do what they could to make a difference rather than be overcome by anxiety.

Amid both the loss of life and economic collapse across the globe it is ultimately people in their communities that are the first line of defence against the devastation we now face. Expecting more and demanding more from those in power is important and justified. But it is we who have the power right now to help those in our neighbourhoods, towns, and cities in greatest need.

We all face a choice whether to hide in fear from the circumstances we face, or to become agents who bend the future to our vision.

There will certainly be many lessons to learn from 2020, but the one I see as most applicable is that rather than dwell on what should be done by those in authority, we can often take it upon ourselves to fix the problems in front of us.

Be the difference you want to see.

This story is part of the Globe’s Tales of the Pandemic series, a collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called published each Monday covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history. All of these Covid-19 stories can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.