Photoshopping history: The true story behind the smirking man of Tuol Sleng

An artist has caused uproar and anguish after photoshopping smiles onto the faces of inmates photographed at notorious Khmer Rouge prison camp S-21. Here, the brother of Khva Leang, incorrectly introduced as Bora in the piece, tells the true story of his long-lost kin

Despite the almost half-century that has elapsed, it takes little effort for Senyint S. Chim to recall the last time he saw his older brother Khva Leang.

They said what would prove their final goodbyes in 1974 as Senyint boarded a Lockheed C-130 Hercules US military plane – bound for training in the States, via Bangkok – from what was then Pochentong International Airport in Phnom Penh.

“The last time was August 6, when I left Cambodia,” said Senyint, then a naval crewman. “At that time we did not know that was the last time we’d see each other. I was expecting to go back in November of 1975.”

Senyint wouldn’t make it back home for nearly two decades. Khmer Rouge cadres marched into the capital on April 17, 1975, declaring victory in the Cambodian civil war. Still in the US, Senyint claimed political asylum, only returning in April 1992 to an almost unrecognisable Cambodia from the one he’d left.

By the time of his long-awaited visit, of his eight siblings, only his two sisters had survived the chaos of their homeland’s war and subsequent four-year reign of the genocidal Khmer Rouge.

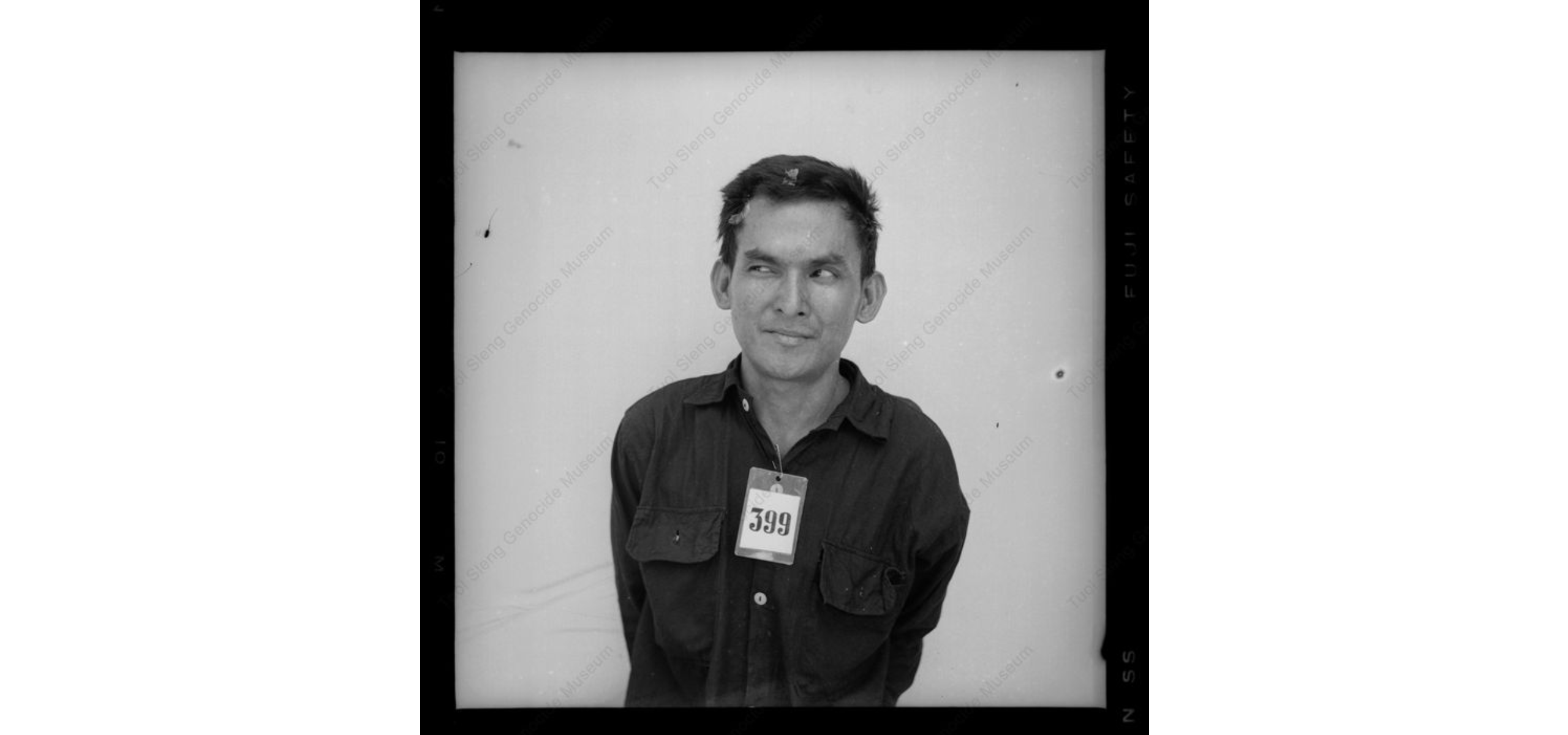

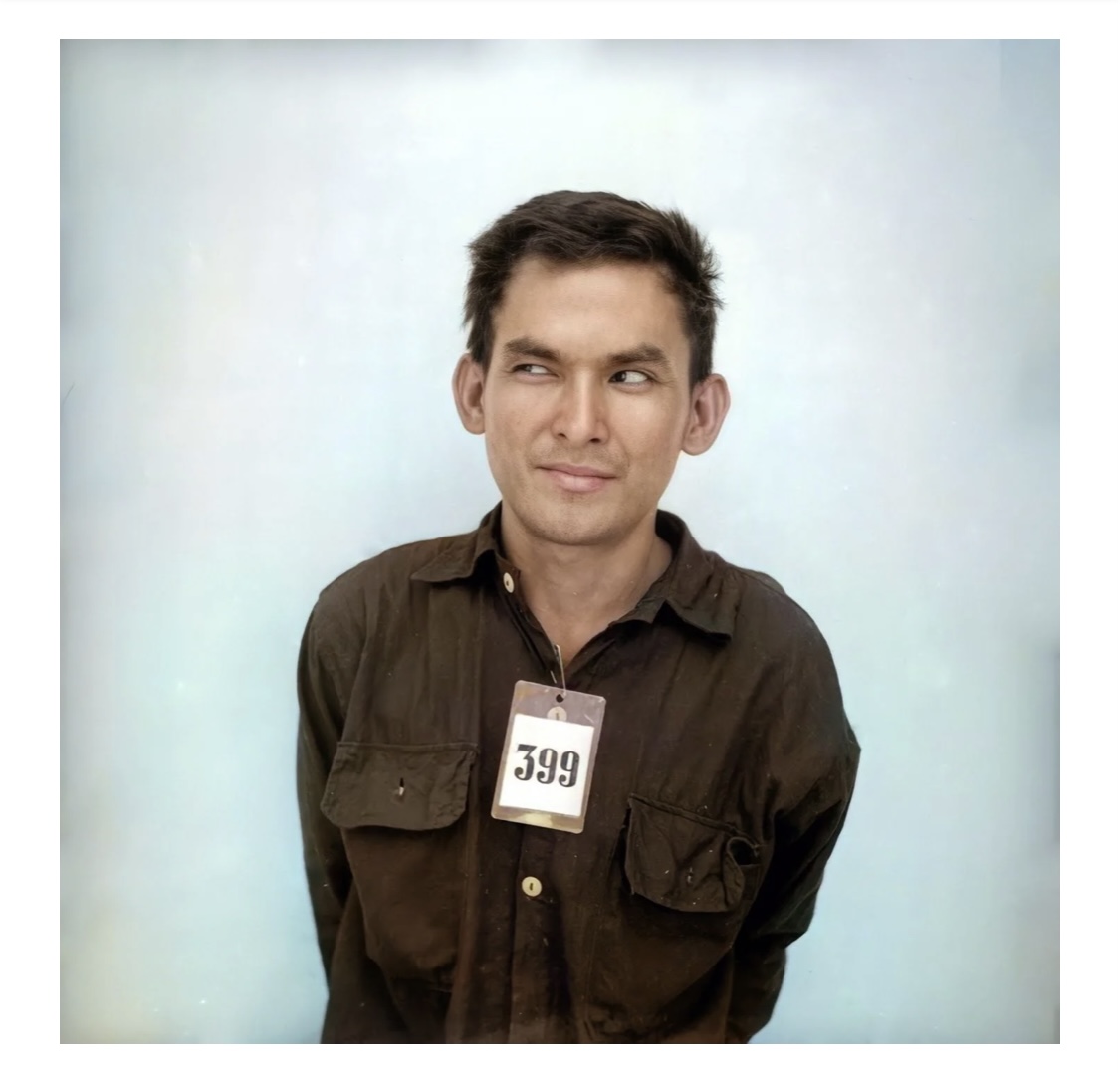

His family’s brutal history from that era was hauled back into a digital spotlight on April 9 in an article on artist Matt Loughrey by media outlet Vice. That piece displayed pictures of prisoners taken at Phnom Penh’s notorious S-21 prison camp – a Khmer Rouge torture and interrogation facility better known as Tuol Sleng – that had been colourised from their original black and white by the Ireland-based Loughrey.

Two days after their publication, early on a quiet Sunday morning at his home in San Diego, California, 69-year-old Senyint was startled to see a portrait of his long-lost brother Leang being shared worldwide.

“I found it about eight or nine o’clock this morning,” he said on a call with the Globe on April 11. “I asked, ‘Does anyone want to let me know what’s going on?’”

A controversial act of revisionism or powerful tribute bringing these black and white images to life, a debate over Loughrey’s edits took on new dimensions when it emerged many of the images had not only been colourised and enhanced, but doctored by the digital artist. Added were calm smiles and pleasant expressions to the inmates, with Loughrey’s digital manipulation erasing the fearful appearances of the originals.

Though Leang’s image was among the few that had remained unchanged beyond being colourised, Senyint was no less disturbed upon seeing his brother’s portrait and the brief biography that accompanied it. That’s because every detail about him, even down to his name, was incorrect.

“I was disappointed that they gave the wrong information, so I wrote to Lydia [my daughter] that I wish they would know the real information about this brother,” he said. “My brother number three.”

It was an act that caused him to revisit and question everything he thought he knew about his brother’s death.

“I felt that was a lack of respect,” he said. “My first impression was that maybe my brother gave them the phony name. But it’s impossible to do that. He was with them.”

Them, in this instance, refers to the Khmer Rouge – one of many details of Leang’s complicated life omitted from the Vice article. Instead, he was touted as a man named Bora and described as “a simple farmer” who was electrocuted and set on fire, information cited to a son of the photographed man.

In fact, Leang was an idealistic teacher who, in an era of bloodshed and post-colonial strife, sympathised with the communist movement and believed in the political project of building a new Cambodia under its ideals.

“It is very typical that teachers care about the poor,” Senyint said. “He wanted to look for someone who can care for the people. To give people fairness.”

You are on the other side politically. But we are still brothers no matter what

The radical ambitions of the Khmer Rouge first required sweeping away the Khmer Republic government of US-backed nationalist Lon Nol, a politician and military leader who rose to power in a 1970 coup d’etat. But despite Leang’s apparent allegiance to the revolution, the schoolteacher would be executed at Tuol Sleng in 1976.

“At that time, he must have been 31,” Senyint said of his brother, five years his senior. Of the 18,145 prisoners brought to Tuol Sleng, only 12 survived.

According to Senyint, the family was largely apolitical, despite him and two of his brothers being members of the military under the Lon Nol government. Senyint remembers having a frank discussion with his brother about their roles on opposite sides of what was then a fast-growing political chasm in Cambodia.

“You are on the other side politically. But we are still brothers no matter what,” Senyint recalled of a conversation he had with Leang. His brother had implored him to go to China, rather than the US, for military training before his fateful final departure in 1974.

“‘Yes, we are still brothers. You don’t go against my way, I don’t go against your way. If one side wins, whoever is on that side has to help the rest of the family,” Senyint remembered his brother responding.

Leang was far from the only Khmer Rouge sympathiser to meet a grim end at Tuol Sleng. As the paranoid regime devoured itself through its reign from 1975-79, Pol Pot and other leaders drove internal purges that sent even some of the most dedicated cadres to the prison for torture before execution at a nearby killing field. In total, it is estimated between 1.5 and 2 million people died during this short period.

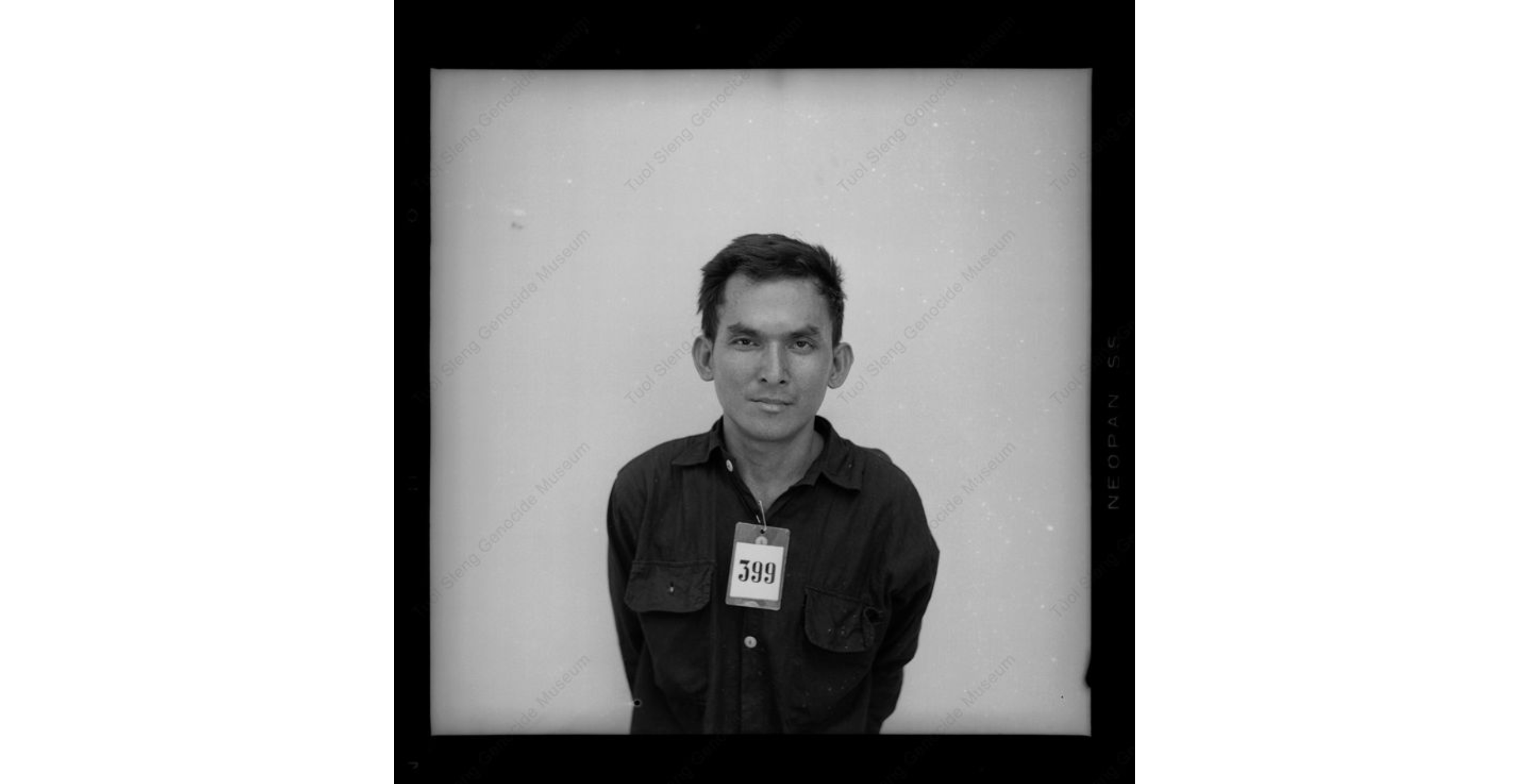

Still, Leang’s portrait – taken in captivity prior to his death, and one of hundreds of thousands taken by the Maoists as they meticulously documented their tyrannical rule – stands out among most.

Senyint himself first saw the image of his brother only a decade ago, with his nephew snapping it on his phone when visiting Tuol Sleng and sending him a photo of it. The former prison is now a museum, serving as a shrine to the victims of past horrors where visitors can see thousands of black-and-white portraits of the camp’s former inmates, almost all of whom wear stricken expressions.

My heart was pounding when I was reading it [the Vice story], because I feel like it’s very cold blooded. You feel terrified, because it’s so close to you, it’s so real to you

But the image of Leang, with his smirk and off-camera glance rightward, doesn’t strike a figure of a man facing imminent torture and death. It was perhaps for this reason that it was chosen by Loughrey as one of many from the prison camp that he would colourise. Along with Leang’s unedited portrait, Loughrey edited smiles onto the faces of several inmates, mostly young boys and girls.

Loughrey declined comment to Globe about the criticism of his work, but has elsewhere dismissed allegations of falsifying history as “nonsense”. He claims alterations were made at the request of families, being quoted in the original Vice article as saying he had worked on Leang’s portrait in particular at the request of the man’s son. Vice referred the Globe to a disclaimer on the article stating its contents were under review, with the article since pulled down.

Commissioned or not, Loughrey’s images have prompted repulsion in the Cambodian community and beyond.

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-CAM) executive director Youk Chhang, himself a survivor of the Khmer Rouge, said that this era remains within living memory for millions of Cambodians, emphasising the potential for this kind of revisionism to cause suffering to survivors.

“My heart was pounding when I was reading it [the Vice story], because I feel like it’s very cold blooded. You feel terrified, because it’s so close to you, it’s so real to you,” he told the Globe. “You rewrite history while it’s still contemporary, it’s still a living history with five million survivors around you. It’s very damaging. The Khmer Rouge is still a contemporary human rights issue.”

Dany Pen, a Khmer-Canadian who lost family members at Tuol Sleng, today a court advocate for victims of abuse and former Commissioner of Human Rights to Bermuda, had also rallied to have the Vice article pulled before it went offline.

“I strongly implore VICE to take down these photos that are promoting white supremacy, cultural appropriation, cultural erasure, and victim dismissal,” she told the Globe. She’s now started a petition demanding an apology be issued (Edit: Vice issued a statement on April 12).

“It promotes harm and brings on psychological and emotional violence towards my Cambodian community.”

The Cambodian Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts issued a statement on April 11 stating it had not worked with Loughrey on the project, which it said “seriously affect[ed] dignity of the victims”, and threatened legal action before Vice removed the images.

This real-life emotional toll can be seen through Senyint’s experience. Thousands of Khmer Rouge victims remain unidentified, and for Leang’s family, the Vice story raised the prospect of a surviving son, an unknown relative, who had provided Loughrey with information about his lost father.

While that seems implausible according to the family’s history, for Senyint’s daughter Lydia, the anguish caused by this fictitious narrative was inescapable.

“That moment, when I read that story and imagined that I could have a cousin out there and not know it, was gut-wrenching,” she tweeted.

Senyint said his older brother and his wife had one child, and perhaps a second shortly before the end. But the couple were both killed by the Khmer Rouge and, as far as Senyint and his surviving family knows, their children were too.

But the loss of his brother’s young family is just one piece of the wider catastrophe that befell Senyint’s kin. On the call with the Globe, he calmly listed the fates of his parents and other siblings, recounting more deaths in less than a decade than most experience in a lifetime.

His father had died in 1970 of natural causes before the transformation of his homeland into Democratic Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge state. His mother lived to see the start of that regime and was eventually killed by it.

There were a total of nine children, seven brothers and two sisters. By the end of the decade, Senyint was the only brother left.

The eldest, a first lieutenant in Lon Nol’s army, was captured and killed by Viet-Cong troops on the Laos border in 1970. The second brother, a banker, was murdered in 1976, the same year as third brother Khva Leang. The fourth brother, who was also a military man and shared the rank of the eldest, died in 1973.

Senyint was the fifth child. His two younger brothers died under the Khmer Rouge regime, though nobody is sure when. His two younger sisters both fled Cambodia and wound up in the US, where they settled in Massachusetts and Nevada.

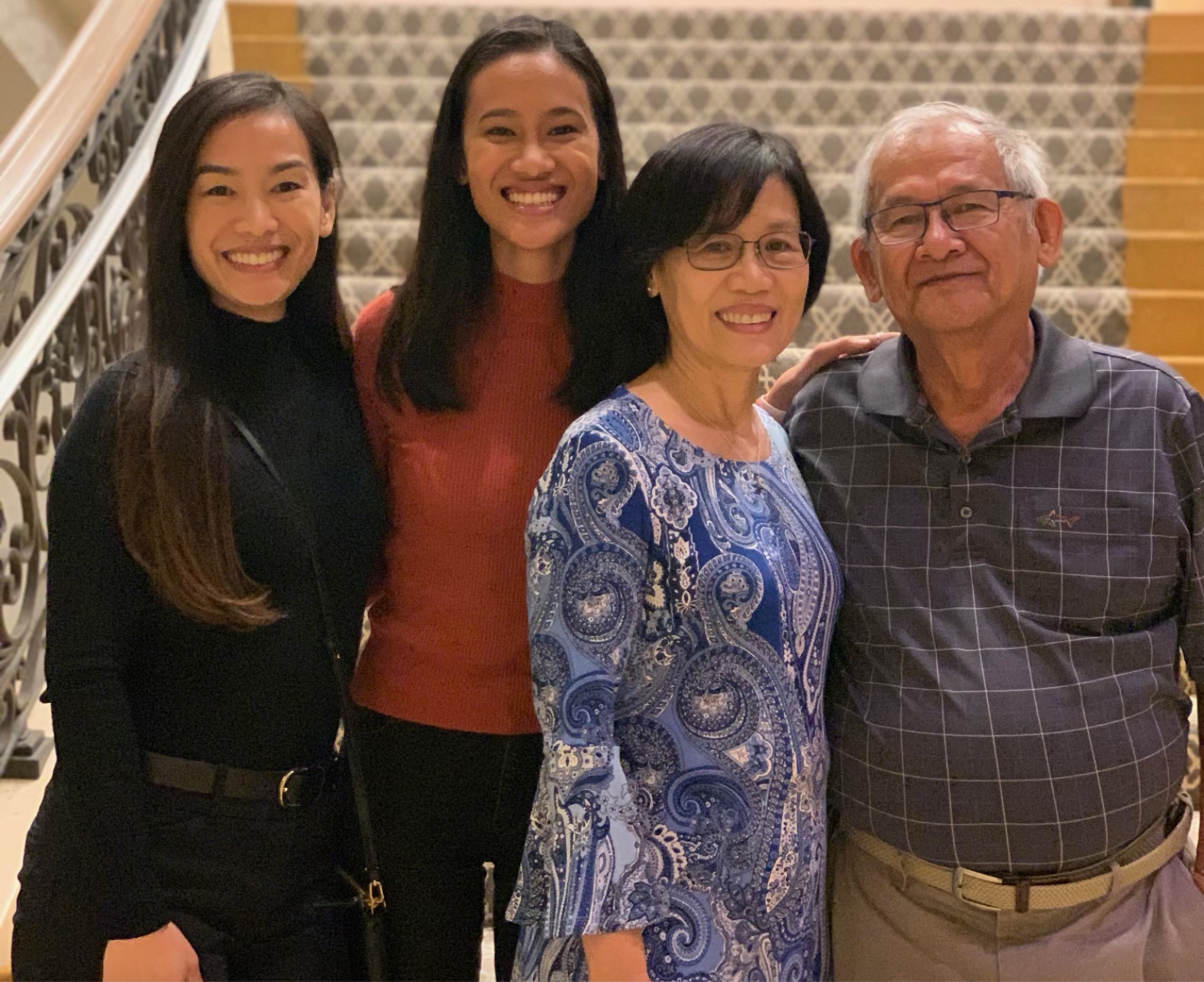

Senyint himself raised two daughters in San Diego, where he worked for 24 years teaching maths and social studies at a public grade school. Serendipitous, perhaps, given Leang’s own history.

In the sweeping tale of the family’s tragedy and exile from home, the focus of the Sunday morning call mostly stayed on Senyint’s third brother, the idealistic, if ultimately misguided teacher Khva Leang. But though the story of the third brother may live on through his portrait, for Senyint, it was that last farewell at Pochentong International Airport in 1974 that left an indelible mark on his character.

“I stress this point to many people – when they leave the country, only take close relatives to come with you at the airport. You never know if you’ll ever go back, or if you go back, you’ll never know if your loved one will be there,” he said.

“When I went back, none of them were there.”