In late-March, the first piece of track of the $6 billion Kunming-Vientiane railway was bolted down, a major milestone for the line linking China’s south west with the capital of landlocked Laos.

An emblematic piece of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and a torch bearer for future regional railway lines, the project has proved impervious to the disruption that Covid-19 has wrought and looks set to be completed by December 2021.

The single-track, 400km-long railway will run through 76 tunnels and over 154 bridges, with trains hitting top speeds of up to 160kmh. While that pales in comparison to the high-speed trains north of Laos’ border, for a country with only a 4km stretch of existing railway, the project will prove groundbreaking in the country’s quest to shed the limitations of its landlocked status.

The railway is seen as a vital link of the Chinese BRI dream being played out on its comparatively tiny neighbour. But Laos has its own ambitions at play. The long, mountainous country has embarked on an ambitious railway plan to cheat geography and become ‘land-linked’ with the help of an infrastructure overhaul financed with outside help.

With the train fast approaching the platform, the tangible benefits of the project remain unclear, more so for those in Vientiane than Beijing. Funded primarily by the BRI’s opaque financing system, the project is a joint venture that is within Laos’ borders, but not of its making. And while railways historically have heralded connectivity and economic benefits for both state and localities, with Laotian demand for the route seemingly not there, scant infrastructure in place to capture revenue and fears of debt defaults for the project, the view is less clear on Laos’ BRI Express.

Origins and financing

Other than the existing 4km stretch, Laos has no rail network, explaining the eagerness of which it has approached the railway to Kunming.

“Building railways has long been a goal for Laos, as it missed out on colonial railway infrastructure in the early 20th century,” explained Keith Barney, a senior lecturer at the Crawford School of Public Policy at Australian National University.

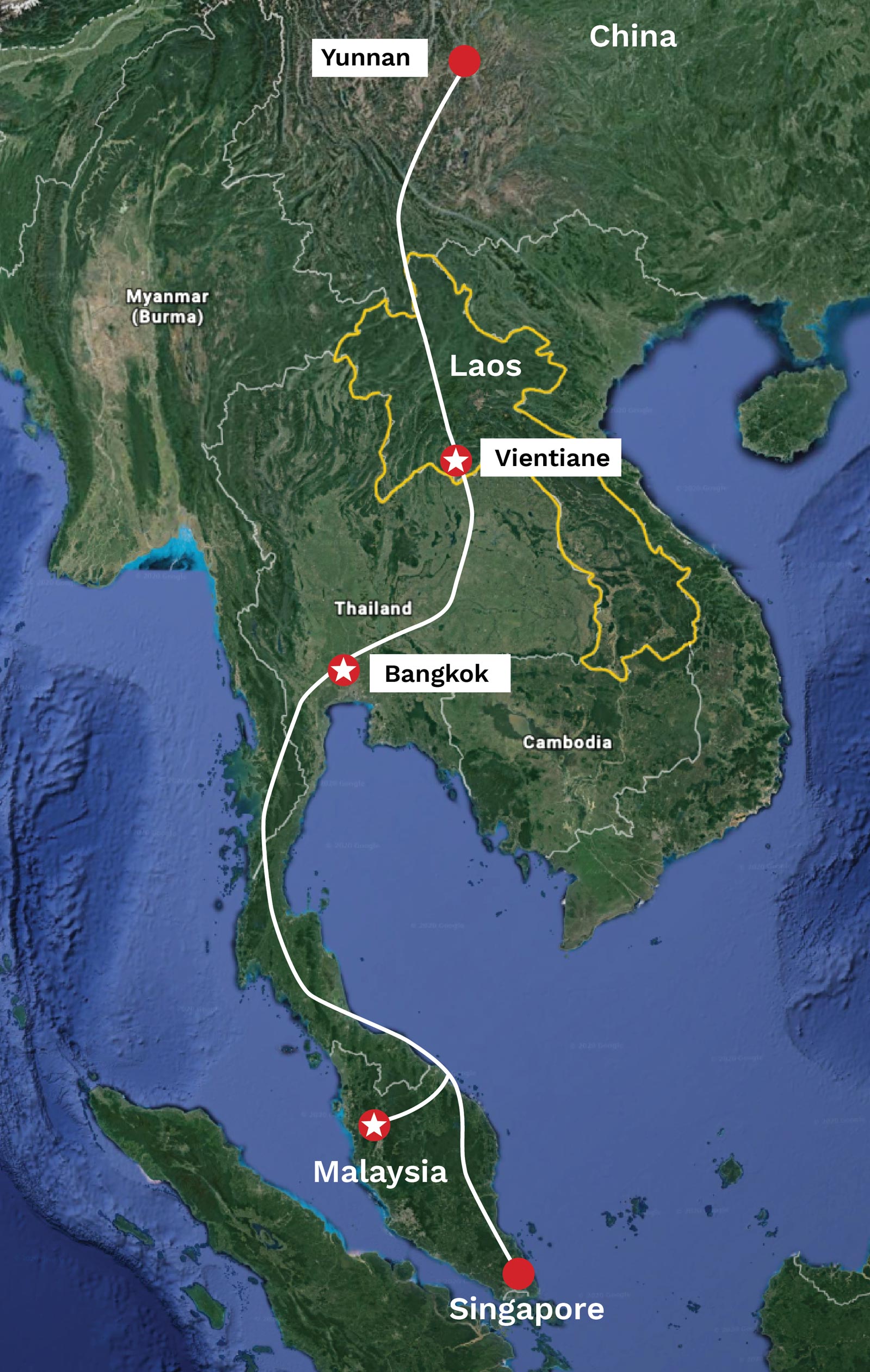

The roots of the project stretch back decades, when the idea of a Kunming-Singapore regional railway was softly proposed at the 1995 ASEAN summit.

The railway is now being realised within a Chinese framework with Chinese money, Chinese workers and Chinese vision

“Actors within the region have looked at this project and struggled to see the viability of it, but then in steps China,” Scott Morris, co-director of sustainable development finance and a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, told the Globe. “It’s become sort of emblematic of its investment projects under BRI.”

Representatives from China and Laos signed a memorandum of understanding for the project in 2010, six years before workers first broke ground on the initial stretch of railway. The China-Laos partnership, however, is weighted more to the former according to Simon Rowedder, a postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore and member of the Max Weber Foundation Research Group on Borders, Mobility and New Infrastructures.

“The railway is now being realised within a Chinese framework with Chinese money, Chinese workers and Chinese vision,” Rowedder said.

What’s more, the project’s investment model would subdue much of the economic benefits for Laos at the construction level, with the vast majority of labourers working on the railway being brought in from China.

Morris said the Chinese investment model suggests a series of diminishing returns.

“The entire financial package rests on the use of Chinese firms, so Laos is not feeling the boost maybe as much as it should have done,” Morris explained.

Like similar projects that fall under the BRI’s obfuscated financing umbrella – the railway seems more like a project within Laos, but not by it, or even for it. Morris said investment entities within the BRI template don’t report financial data “in any sort of transparent fashion”, making it difficult to parse out what their funding packages actually consist of.

This was the case for the Kunming-Vientiane railway, which Morris said carried a price-tag beyond what the Laotian government was able to borrow on its own. As a product of that, the financing structure of the project forms a 70-30 ownership split, made up predominantly of Chinese loans and equity investments. The World Bank estimates China’s share of the financing to be $4.11 billion.

“A lot of criticism levelled at BRI goes towards this issue, where you have a government owned-Chinese entity that is taking a majority stake in massive infrastructure,” Morris said. “It’s politically sensitive, but the only way this project was going to get done is with this equity.”

Laos also had to turn to China to help fund its minority stake, taking out a $480 million loan from China’s Export-Import Bank, and further $250 million from the government budget, and it will need the railway to generate enough revenue to service the loans, or risk defaulting.

“Even for Laos to fund its minority stake, they needed a huge loan from the Chinese government – which makes it particularly convoluted,” Morris said.

China’s regional network aspirations

The stretch from Kunming to Vientiane is being built with an eye to the Chinese aspiration of a regional railway network. While not being a direct train, there are hopes that the long-mentioned Kunming-Singapore railway will one day see light. A Thai-Sino high-speed rail line from Bangkok to Nakhon Ratchasima, to eventually link towards the Laotian border, will be officially agreed and signed in October.

The rest of the proposed project has run into more trouble, however, with bilateral agreements to build railways from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur and north to Bangkok long-delayed, and the rest on shaky political ground. It will likely take a number of decades to realise a regional railway network south of Bangkok, if it is ever to happen.

Economically, isolated stretches of rail are not a high priority for nations looking for a return on multi-billion-dollar investments. As such, the Kunming-Vientiane stretch may require an accompanying regional rail network to realise its full potential.

“At the minimum you need a regional railway network for this stretch of track to make sense,” Morris said. “But then, in such a framework, you have some countries who can reap the rewards while some will miss out.”

However, Parag Khanna, author of The Future is Asian: Commerce, Conflict & Culture in the 21st Century, believes the very existence of such a railway will see Laos reap the rewards, even if further down the line.

“A fundamental point is that infrastructure does not follow the pattern of strategic ownership,” Khanna explained. “While it can be viewed as a Chinese tool, the bottom-up view is that infrastructure is not linear. It empowers countries to diversify their economies – and with the case of Laos, it can provide it with the economic tools to one day resist the encroachment the railway itself represents.”

Indeed, Laos’ wider rail ambitions can be seen in an extension of the existing 4km line to Vientiane, in which a two-track railway from Savannakhet in the west, to Lao Bao on the border with Vietnam, has been proposed and is awaiting construction. From Lao Bao the railway would then travel across Vietnam, to Dong Ha.

In late-2019, it was also announced that the Indonesia Railway Development Consortium was planning to build a 400km route from Thakhek in Laos, to Vung Ang Por in Vietnam.

“No one pays as much attention to this railway, a part of the East-West Economic Corridor between the two countries [Laos and Vietnam],” said Rowedder. “Laos has had to calculate how to pragmatically benefit from its context, so it’s not just a picture of ‘victim-Laos’.”

From a classical development geography perspective, it makes sense that China would seek to incorporate new regions and frontier zones into its economic sphere

That would require the will and vision on the part of Laos to make this new railway network, most importantly the Kunming line, work for its own needs. However, other commentators argue the railway’s commencement may just further solidify Laos’ dependence on China, locking in the smaller country’s role as a transit line for the larger nation. Barney believes China doesn’t just want the railway for its connectivity value, but also its ability to extend influence beyond its borders.

“From a classical development geography perspective, it makes sense that China would seek to incorporate new regions and frontier zones into its economic sphere,” Barney said.

Rowedder echoed that sentiment, adding the railway doesn’t just speed up the influx of Chinese capital and investment, but also ties Laos to it. In his view, the project is part of the stirrings of an “economically recovering giant in China, who’s sort of pushing this project through a host with a struggling economy” to advance its own longer-term domestic goals.

Arguably, it’s being built with China’s south west in mind, where a push to open up the region and Yunnan province, levelling it up with the east coast, is underway.

“This western push has been targeted domestically for a while,” Rowedder explained. “There has been long-term planning on how the west of China can benefit from regional connectivity, trade and investment. The railway is a logical extension of what we’ve seen before.”

Domestic boost or a Laotian white elephant?

The project has the potential to be an economic boost for Laos, as well as improving connectivity to China, and further afield, the region. But to ensure success, it must be primed to capture the benefits in order to avoid the railway becoming a white elephant.

“It’s certainly an ambitious state-building project for Laos, but whether it will prove to be a reasoned gamble will depend on what Laos makes of the railroad,” Barney said. “The government seems to be confident that ‘if you build it, they will come’.”

In the long-term, that doesn’t make for a convincing business plan.

“The economic impacts that the railways might bring must be observed for more than 10 years,” said Narut Charoensri, a lecturer in international affairs at Chiang Mai University. “We need more evidence-based analyses to measure economic change, in the long-term, for this project.”

On a recent field research trip to Laos, Rowedder picked up a brochure detailing the apparent economic benefits of the railway.

“The first thing on the list was income generation from transit fees,” Rowedder recalled. It would be hoped that a $6 billion railway would bring about more than just transit fees. “Laos may have the infrastructure, but without the soft infrastructure to accompany it, it will always remain a venue of ‘transit’.”

The ‘soft’, supporting infrastructure needed to accompany it is central to Laos being able to capture the revenue from the line. Well-maintained feeder roads, storage facilities, efficient border and customs services for passengers and goods, responsive regulatory frameworks and enhanced tourism infrastructure, among other things, are all needed alongside the railway.

It’s an ambitious ticket to punch before the railway’s grand opening, scheduled for 2021. Rowedder, however, noted that the picture on the ground in Laos is different to the prevailing reportage of it.

“There is optimism and fascination in Laos about this,” he said. “The picture on the ground is more nuanced than what has previously been reported.”

Rowedder explained that while issues remain with land settlements, he found that people he met were excited for the railway, “as long as it didn’t go through their backyard”.

Before Laos’ apparent ‘railway revolution’ comes the Kunming line, which will act as the guinea pig for similar projects within the region. And with an immense cost, short-term gains seemingly minimal and long-term benefit unclear, once Laos’ shiny new railway gets the green light, the jury will be out whether the economic good was worth the outlay, and whether “if you build it, they will come” really is a credible strategy.