When asked to name the most eventful year since the end of World War II, 2020 would probably top most people’s lists.

Beginning in January with the American assassination of Iranian General Qasem Suleimani, then dominated by the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus and police violence against African-Americans that have sparked protests worldwide, before culminating in attempts at discrediting the democratic process in the US and Myanmar, 2020 will go down as one of the most consequential years in recent history.

While all that is hard to beat, the year 1979 is another worthy candidate for the title of “Most Eventful Recent Year”. 1979 saw conflicts breaking out – from Indochina in the east to Central America in the west, Ireland in the north and Angola in the south – that destabilised the bipolar order of the Cold War and ushered in the age of intensified ethnic and sectarian conflicts that still characterises our present-day international order.

And though the Cold War only ended in 1989, the seeds for its collapse were planted a decade earlier in the borderlands of Southeast Asia in 1979.

The year started with the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in response to years of border provocations, taking the capital Phnom Penh on January 7. While the Vietnamese liberated the country from the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge, they failed to capture their leaders and garner international support for the newly-installed government. With backing from China, ASEAN, and the West, the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, militarily dominated by the Khmer Rouge, would retain the Cambodian seat at the UN and drag out a protracted conflict against the Vietnamese- and Soviet-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea for the next decade.

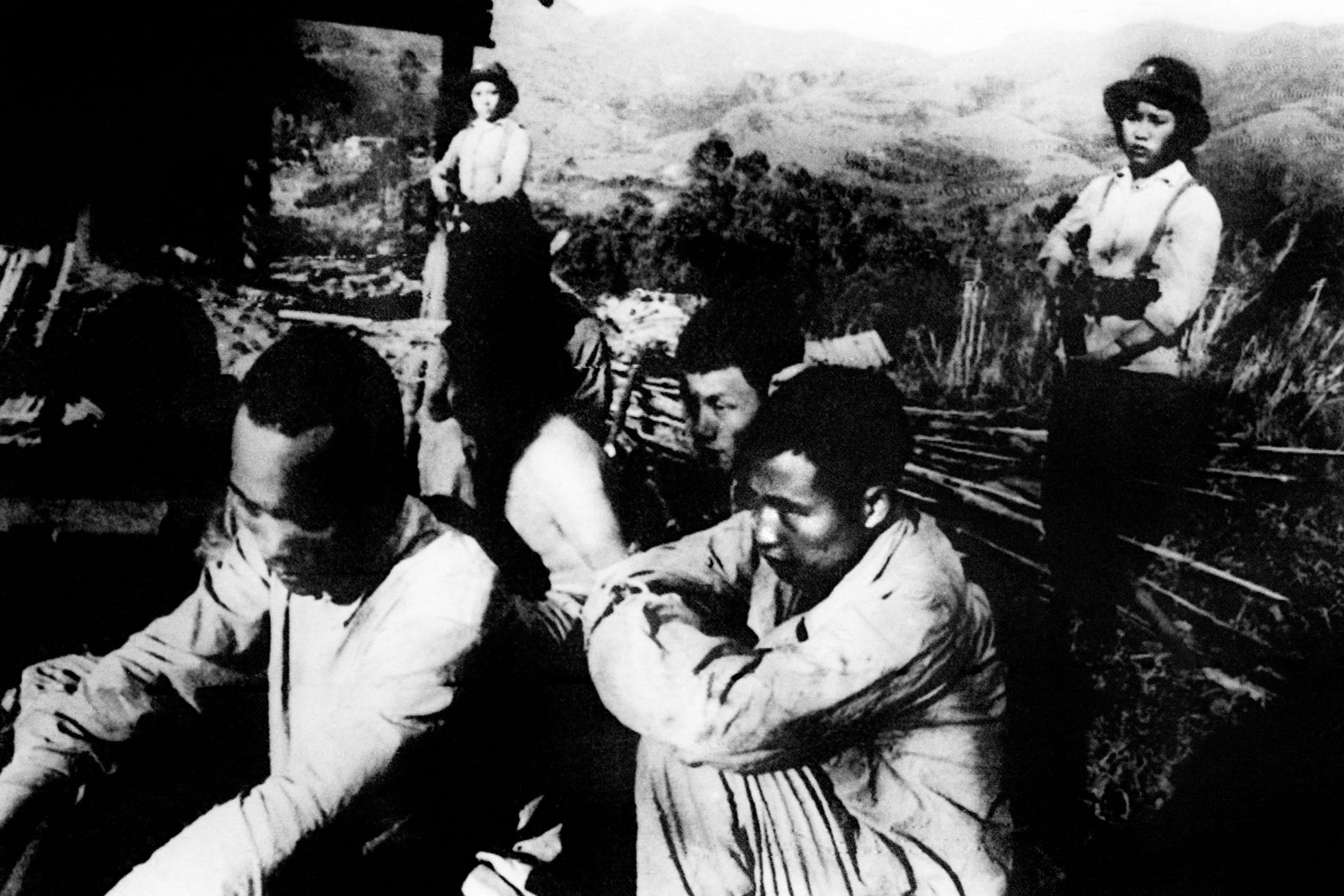

Chinese Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping saw the Vietnamese attack on one of their few staunch allies, Cambodia, as part of a Soviet plot to encircle China. In response to the Vietnamese invasion, on February 17, 1979, fourteen Chinese divisions numbering around 200,000 troops invaded northern Vietnam. By the time they withdrew a month later, both sides had suffered military casualties in the tens of thousands, and Vietnam’s border provinces with China laid in ruins. Up to a million ethnic Chinese would end up fleeing Vietnam, and even today relations between the two erstwhile allies have still not been fully repaired.

Relations between Beijing and Moscow had begun to crack as early as 1956 when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave a secret speech denouncing Stalin’s cult of personality, which Chairman Mao Zedong took as a personal attack on his brand of Communism. Throughout the 1960s, as Soviet and Chinese forces engaged in a number of border skirmishes of their own, they also jockeyed for influence during the Second Indochina War, with the Soviets delivering advanced weaponry and the Chinese providing civilian supplies and light arms to the North Vietnamese forces.

Throughout the war, the Vietnamese tried to maintain a balance between the Soviet Union and China. But Sino-Vietnamese relations nosedived in 1977 when the Khmer Rouge, a Chinese ally, began their irredentist attacks on the Mekong delta, and Sino-Vietnamese border negotiations broke down late that year.

Vietnam’s untimely nationalisation of 30,000 businesses in the South in March 1978 and unification of its currency in May 1978 then raised Chinese suspicions that Vietnam was unfairly targeting the ethnic Chinese population, many of whom were business owners. The point of no return was when Vietnam joined the Soviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance in June 1978. China suspended all aid to Vietnam on July 3, and closed their shared border on July 11.

When I visited the Soviet Union that September of 1970 and met Premier Kosygin at his holiday dacha on the Black Sea, the Soviet leaders were expansive and assertive, confident that the future belonged to them

The Chinese invasion of Vietnam seven months later, coming just a month after Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the US to normalise relations, was primarily to show Beijing’s willingness to join hands with the US to contain the Soviet Union.

It was a move that seemed to violate a golden rule of Realist balance-of-power theory. Insofar as the Soviet Union remained weaker than the US throughout the Cold War, it would seem unwise for the Chinese to help the US defeat the Soviets and reign supreme on the global stage.

The Third Indochina War (the preferred designation among many academics for the connected conflicts between Vietnam, Cambodia, and China from 1979 to 1989) sent Realists scrambling to revise this age-old theory. Among the most popular innovations was Harvard political scientist Stephen Walt’s “balance-of-threat” theory, which posited that Deng felt more threatened by the USSR than the US, the latter’s greater strength notwithstanding.

Walt’s major contribution was in distinguishing the perception of power and threat from objective measurements of power. Today, knowing that in 1979 the collapse of the Soviet Union was merely a decade away, it is hard to imagine how at the time, most prominent commentators believed that the Soviet Union was actually on the rise vis-à-vis the US. But the geopolitical landscape at the time looked very different.

Writing in Foreign Affairs in January 1978, policy wonk Helmut Sonnenfeldt fretted that “Soviet military power continues to grow and Soviet involvements in world affairs, whatever the fluctuations, remain on the rise.”

As Fredrik Logevall and Campbell Craig have shown, American politicians, journalists, and academics all made (in)famous careers out of overblowing the Soviet threat, despite the US’ economic and technological edge versus the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War. But the Americans were not alone in overestimating Soviet power in the 1970s – Deng Xiaoping and then-Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew certainly felt the same way, as did the Soviets themselves.

In his memoirs, Lee Kuan Yew recalled: “When I visited the Soviet Union that September of 1970 and met Premier Kosygin at his holiday dacha on the Black Sea, the Soviet leaders were expansive and assertive, confident that the future belonged to them.”

By contrast, on July 15, 1979, US President Jimmy Carter delivered one of his most famous speeches in which he spoke of “a crisis of confidence” threatening the “unity of purpose” of his foundering nation.

Around the world, there was an overwhelming perception by 1979 that on the global chessboard, the Soviets were getting everything they wanted, and America was in retreat. Not only did the US have to suffer the indignity of military withdrawal from Indochina in 1973 only to witness its allies fall to the Communists in 1975, but the Americans also seemed to be losing their grip everywhere else.

In the 1974 military coup in Ethiopia and its subsequent war with Somalia in the Ogaden in 1977-78, as well as the 1975 civil war in Angola, pro-Soviet revolutionaries gained significant ground in Africa with the help of Cuban expeditionary forces. Increasingly fearful, America and its allies around the world resorted more and more to violent repression of leftists, including the 1973 coup against the democratically elected President Salvador Allende of Chile and the 1976 massacre of leftist activists at Thammasat University in Bangkok, Thailand.

Despite this reactionary violence, 1979 would appear to be the high-water mark for the Soviet Empire and a nadir for the American, and not only because China failed to dislodge Vietnam from occupying Cambodia in March 1979.

On February 3, the Shah of Iran, a long-time American ally, was forced to leave the country. By November, a theocratic regime had been established and 52 Americans taken hostage when students stormed the US embassy in Tehran. The Iranian Revolution would severely destabilise the global economy, causing an oil crisis that would be further exacerbated by the outbreak of a decade-long war between Iran and Iraq in the following year. Not far off, and on Christmas Eve 1979, Soviet troops entered Afghanistan and began an occupation there that would last ten years. Meanwhile, in America’s own backyard, pro-Soviet revolutionaries took control of Nicaragua and began a decade-long civil war in El Salvador.

On the whole, the year was seen as such a humiliation for Carter and the US that he’d soon be unseated by Ronald Reagan by a landslide in the 1980 Presidential Election.

The Third Indochina War, too, was a conflict between apparent ideological allies that had its origins in Pol Pot’s dream to restore the glory of the Khmer Empire by retaking the Mekong delta from Vietnam

But despite the perception of overwhelming Soviet success and American disorientation, 1979 would ultimately prove to be the year that would reverse the Soviet Union’s diplomatic and military fortunes.

The Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan were both initial military successes that turned into costly quagmires for the Soviet bloc, which would eventually force both countries to largely abandon the fully-planned economy by the mid-1980s.

1979 would also herald a new era when ethnic and sectarian conflicts came to the fore to eventually overshadow the ideological fault lines of the Cold War. In June, Pope John Paul II visited his native Poland, triggering an unprecedented revival of faith in the Communist nation, and perhaps inspiring support for the independent Solidarity trade union – founded a year later and central in the demise of Communist rule. On August 27, 1979, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, a prominent member of the British royal family, was assassinated by members of the Irish Republican Army, greatly escalating the sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants in Ireland and the United Kingdom known as “The Troubles”. And it was in the creation of a modern theocracy in Iran and in the battlefields of Afghanistan that political Islam became once again a force to be reckoned with on the global stage, resulting in the ill-fated ‘War on Terror’ decades later.

The Third Indochina War, too, was a conflict between apparent ideological allies that had its origins in Pol Pot’s dream to restore the glory of the Khmer Empire by retaking the Mekong delta from Vietnam. It is imperative that in remembering it today, we are aware of the global context in which the war occurred. It was one among a large number of significant conflicts that characterised 1979, a year that was perhaps even more eventful and pivotal than 2020 in shaping the course of world history.

Hoang Minh Vu is a diplomatic historian of Cold War Southeast Asia and is currently Visiting Faculty in History and Vietnamese Studies at Fulbright University Vietnam. He obtained his PhD in History from Cornell University in 2020 and holds a BSc. in International Relations and History from the London School of Economics and Political Science.