“I wish the current climate crisis was approached and handled, as if we’d just discovered that a large asteroid is hurtling towards us and is expected to hit and wipe out most life on Earth in 2030,” said Belgian-born environmental engineer and roving science communicator Stéphane De Greef. “This would become humanity’s top priority over anything else.”

Every news story and climate science report tells us that we are hurtling towards calamity. Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the US National Centre for Atmospheric Research, told Southeast Asia Globe that failing to take global actions to mitigate climate change meant that the whole world would “suffer the consequences”.

“Recognising that changes are already underway, what they are, and their impacts and risks is essential,” he said.

Nipuna Kumbalathara, Asia media and communications lead for Oxfam International, was more blunt.

“We’ve got little time left on the planet if we don’t act now,” he said.

But with only a handful of countries on course to meet their Paris Agreement commitments while rising tides and temperatures threaten to blot out life in Jakarta, Ho Chi Minh City and Bangkok, climate action just doesn’t seem to be a priority for the human race.

No one knows this better than 16-year old student-turned-activist Greta Thunberg. The Swedish firebrand rose to fame for her outspoken statements calling out leaders and nations for their failure to face up to the climate challenge, inspiring thousands of students like her across the world to take to the streets in protest.

In her address to the Austrian World Summit in May, Thunberg had a message for politicians in the audience: “We will not let you get away with it.” She then turned to the media. “People listen to you, they are influenced by you, and therefore you have an enormous responsibility.

It’s 2019. Can we all now please stop saying “climate change” and instead call it what it is: climate breakdown, climate crisis, climate emergency, ecological breakdown, ecological crisis and ecological emergency?#ClimateBreakdown #EcologicalBreakdown

— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) May 4, 2019

It’s a responsibility that we have no choice but to take seriously.

For Jessica Troni, lead on climate change adaptation for the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the media has a duty to break down complex issues for the general public.

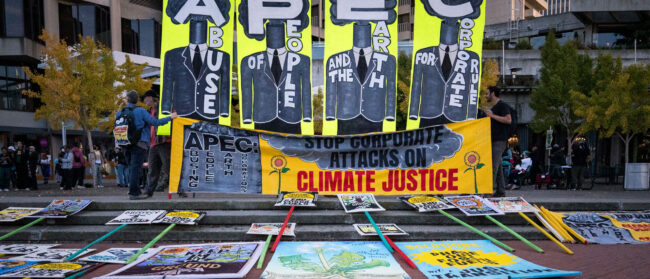

“Recently there have been many citizen movements to rally for action on climate change that have been televised and reflected in print media,” she said. “The media does also have a responsibility to educate in terms that people can understand. Projecting these messages is key to galvanising for support for greater climate action.”

This messaging could be what ultimately drives government action, according to international legal expert and founder of consulting firm Green Transparency Shirleen Chin.

“The purpose of changing the language is to reduce the time it takes for governments and corporations to push the panic button and start doing something,” she said.

“Climate change’ is a passive phrase in an extremely dire world,”

Nipuna Kumbalathara, Asia media and communications lead for Oxfam International

In May this year, the Guardian made the unprecedented decision to switch up their in-house style guide to “better convey environmental crises” – and that last word is important.

Up for review were three terms: “climate change”, “global warming” and “biodiversity.”

In place of “climate change” the new style guide prefers “climate emergency, crisis or breakdown”. “Global warming” is out, the more strident “global heating” is in. Perhaps most controversial of all, “biodiversity” will be discouraged in favour of “wildlife” – though only in certain instances.

The Guardian’s environmental editor Damian Carrington was sure to add that the old terms would not be banned entirely but rather used sparingly. Other media outlets have since taken up the mantle, such as CBC, Canada’s national public broadcaster.

A change of (dis)course

Besides media actors, the Guardian are in good company, joined not only by leading lights in climate science but by many of those working to alleviate climate impacts on the lives of people around the world, including those who will be hit the hardest.

“It is extremely important that we look for every possible avenue, including through media outlets, to build and strengthen the narrative around the climate crisis and the urgency around the issue,” Oxfam’s Kumbalathara told Southeast Asia Globe via email.

The planet is burning. But will turning up the heat on the language we use about it help? We asked climate change experts what they thought of the move.

“We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue,” said Guardian editor-in-chief Katharine Viner. “The phrase ‘climate change’, for example, sounds rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity.”

Kumbalathara agreed.

“Climate change’ is a passive phrase in an extremely dire world,” he said, adding that failure to prevent rising global temperatures would mean “100s of millions driven into poverty, massive food scarcity, loss of life [and] biodiversity.”

Bill Laurance, a conservation biologist at James Cooke University in Australia, said that climate change didn’t cut it. “‘Climate change’ sounds neutral and pedestrian, when the situation we face is rather more like someone on a beach who’s noticed the water level has abruptly dropped.”

Some might call that a “water-level change”, he said – others would call it an impending tsunami. For Laurance, the framing matters.

“We would react to those two situations very differently,” he said.

Not all media were keen for a change, however. The New York Times is one publication standing by “climate change”.

“We use various terms, ‘climate change’ being the most frequent,” said a spokeswoman. “And we strive to define what that means in the context of our stories.”

“People die in heat waves, so let’s not mince words”

Daniel Cullenward, policy director at Near Zero

For some, that might be playing it too safe.

“I think it’s erring on the side of caution,” said Laurance. “But that may be appropriate for the Times, given the diversity of their readership, which includes some conservative readers that might overreact to new terminology.”

Those in the know agree that the state of the earth calls for stronger language.

“’Climate crisis’ and ‘climate emergency’ are better descriptions of the current situation,” said De Greef. “What we’ve been experiencing over the last decades and will go through for decades to come is nothing short of catastrophic if you’re looking at the big picture.”

“Global warming doesn’t capture the scale of destruction,” said Richard Betts, head of Climate Impacts strategy at the Met Office Hadley Centre for Climate Change during his address at the UN climate summit in Poland last year. “Global heating is technically more correct, because we are talking about changes in the energy balance of the planet.”

Few disagree that “global heating” makes more sense.

“‘Heating’ better captures the nature of the expected impacts,” said Daniel Cullenward, policy director at Near Zero, an organisation fighting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “People die in heat waves, so let’s not mince words.”

But temperature change isn’t all we have to worry about. “Changes to precipitation patterns and sea level are likely to have much greater human impact than the higher temperatures alone,” according to NASA’s website.

Perhaps this goes some way towards explaining why De Greef sees ‘global heating’ as “still an understatement to describe what we’re going through.”

Others maintain that language that fails to identify the main political and economic drivers of greenhouse gas emissions – the fossil fuel industry and their allies in governments across the globe – will never go far enough. UK-based media consultant Paul Dawson said that the media “could do a better job of highlighting where public policy is hindering progress.”

“[Stories on climate change could say] something along the lines of ‘due to climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels, many of which are subsidised by many of the leading economies of the world’,” he said.

This is the change which elicited perhaps the strongest reaction from the experts.

“I am surprised they are discouraging the term “biodiversity”,” said Alex Ball, programme manager at WildGenes laboratory, Edinburgh Zoo. “I do not think that the words ‘biodiversity’ and ‘wildlife’ are easily interchangeable.”

Ball explained that biodiversity “encompasses all living things on Earth” from animals down to the bacteria and viruses, whereas wildlife is only a “tiny proportion of biodiversity.”

“A landscape filled with wildlife is not necessarily biodiverse as ‘lots of wildlife’ can also refer to high numbers of a single or very few species,” he said.

Others were more supportive of the shift towards favouring “wildlife”.

“To me this appeals more and resonates with people,” said Thomas Gray, a conservation biologist based in Southeast Asia since 2005. “And, particularly in much of Asia, there is an urgency to preserve wildlife above wider biodiversity.”

“This lack of concern and action, despite all the red flags we’ve seen since the 1980’s, might be the downfall of humanity”

Environmental engineer and science communicator Stéphane De Greef

UNEP’s Troni was ambivalent towards the change.

“We understand that accuracy sometimes needs to be sacrificed to get the idea and messaging across to non-technical audiences,” she told Southeast Asia Globe. “Still, wildlife conjures images of mega fauna and does miss an important point about biodiversity – that it is the entire socio-environmental system including plants and micro-organisms.”

For Green Transparency’s Chin, the change strikes “a more common chord with laypeople.”

“Society consists of a majority of non-academics,” she said. “It is after all business practices and lifestyle changes that we are aiming to change… simplifying the language… makes sense.”

Conservation biologist Gray agreed that the new language hit home harder.

“I think ‘wildlife crisis’ is more meaningful for more people than ‘biodiversity crisis’,” he said. “We all love wildlife…. This is how we should be messaging the environmental crisis.”

Troni hoped that the changing language would create a greater sense of urgency not just among the public, but the private sector.

“Business should start taking responsibility for the part they play in environmental degradation and pollution processes,” she said, adding that she believed the media could influence business decision-making – if it finds the right words.

Changing more than words

Perhaps if there were an asteroid on a direct crash course for Earth, as in De Greef’s wish, people would sit up and pay attention. But the current climate crisis is not an asteroid.

“It’s a much slower but equally damaging phenomenon that is unravelling over a few decades, so we pay no attention to it,” he said.

Instead, we are like the “frog sitting in the pan and the water temperature is rising, yet not fast enough to scare us and make us jump out,” he said.

“This lack of concern and action, despite all the red flags we’ve seen since the 1980’s, might be the downfall of humanity.”

For some, the path to revolution is clear: the replacement of our political economy with one that puts sustainability above the relentless pursuit of profit.

“We keep on consuming, our economies keep on growing,” De Greef said. “We keep on harvesting natural resources as if we were not in a finite, isolated, closed system called Earth.”

It’s easy to be gloomy given the constant drip of doomsday headlines coming out day after day pronouncing the precarious state of the planet. But James Cooke University’s Laurance remained hopeful that changing the words we use to talk about the current crisis might help us rewrite the way the story ends.

“Language is important – it shapes how we think about the world,” he said.

UNEP’s Troni said that people needed to be reminded that they alone had the power to change the fate of the planet.

“Positive messaging usually works better with people than negative messaging,” she said. “Ultimately though, a combination of positive messaging and ‘crisis’ messaging is needed for people and politicians to understand the enormity of the challenge facing humanity – and the fact that managing it is entirely possible, and in our hands.”

Words matter. That’s why Southeast Asia Globe is changing the way we talk about the current climate emergency. We’re not just facing climate change – we’re staring down a climate crisis. We’re not going to talk about global warming – now, we’re talking about global heating. And where it fits, we’re going to be talking not just about threats to the Earth’s biodiversity, but to its wildlife.

We’re running out of time to fight back against climate crisis. The least we can do is be honest about what we’re facing.