The cool stone pillars of the U.S. Supreme Court building were hit by intense summer heat and the ire of hundreds of protesters following the controversial 24 June overturning of Roe v. Wade.

The decision to invalidate a 1973 court ruling and grant individual states power to set their own abortion laws is likely to ban the termination of pregnancies in at least 26 of the 50 American states and triggered a wave of protests across the country. Some demonstrations have been met with violence.

Carrie Tan watched the events in America unfold as she wound through the crowded streets of West Bali on a four-hour car ride towards Denpasar Airport. The Singaporean MP and founder of Daughters of Tomorrow, a charity supporting women from low-income families towards employment, had come from the annual Asian Venture Philanthropy Network (AVPN) conference, a side event of Indonesia’s G20 Summit.

AVPN is Asia’s largest social investment community working to drive funds towards social and environmental impact in the region. The organisation launched the Asia Gender Network, the world’s first pan-Asian platform committed to mobilising investment from the private sector towards gender equality initiatives in 2021.

For Tan, the contrast between the progress achieved in Asia and the regression in the Western superpower was disquieting.

“Such a regression in human rights within a democracy shows that it’s possible for ‘values’ and the perception of ‘rights’ to be corrupted and given power perversely if we are not careful,” she said.

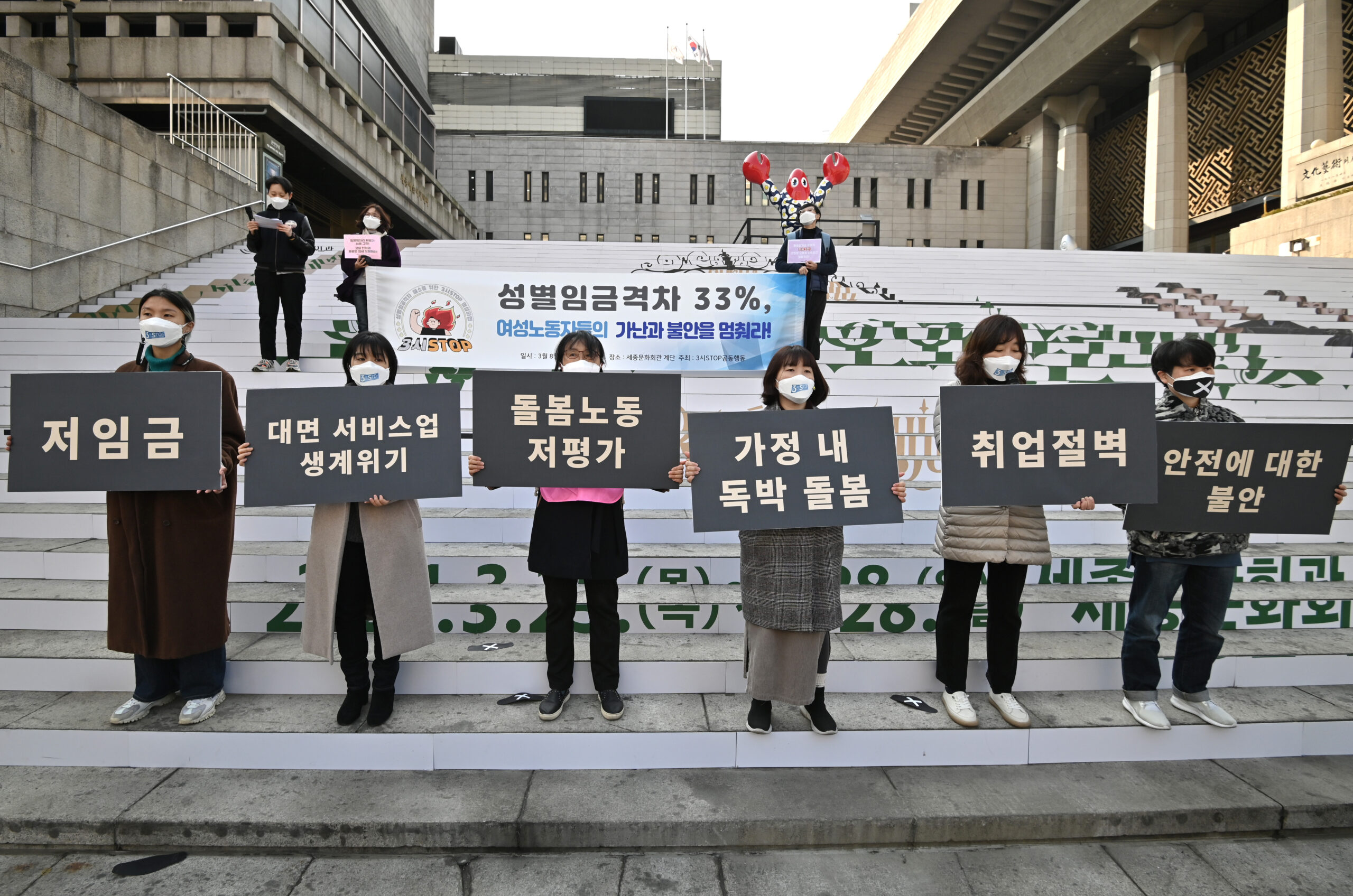

The events in the U.S. reminded Tan of starkly different demonstrations in South Korea just six months earlier, when the country’s growing #MeToo movement and rise in young women fighting to legalise abortion were met with harrasment from anti-feminist group New Men’s Solidarity, known for targeting female victims of online sexual harassment and women’s rights advocates. The YouTube group has 508,000 subscribers.

Tan’s next planned trip is to Seoul to run a series of workshops sharing her expertise and experience of women’s rights advocacy in Singapore.

The city-state is by her own claims “doing rather well” in the fight for women’s rights, she said. The Red Dot was one of the first Asian countries to legalise abortion in 1969. A government announcement in March allowing all women between 21 and 35 to freeze their eggs from 2023 was a milestone in women’s reproductive choice. But there is progress to be made. According to women’s rights and gender equality group AWARE, 57% of Singaporeans, including 43% of women, believe men are the head of the household and should lead decision making. One in 10 women in Singapore experience physical violence at the hands of a male during their lifetime.

Tan spoke to Southeast Asia Globe about the setbacks and successes of Singapore’s journey to parity, why the patriarchy is a common enemy across all genders and the policies needed to drive change.

What is your view on the recent overturning of Roe vs. Wade in the U.S.? Do you think this will impact how abortion is viewed in Singapore?

It is quite alarming for me that something this extreme could happen in a democracy. It tells us that people can and will choose something extreme if they perceive something important to them as under threat, such as their beliefs and values, to the detriment of the rights of others. Such a regression in human rights within a democracy shows that it’s possible for “values” and the perception of “rights” to be corrupted and given power perversely if we are not careful.

What challenges do you think face women’s rights movements in Southeast Asia?

Women everywhere continue to carry the burdens and baggage of the role models they saw in their mothers and grandmothers. What was possible and not possible for the past generation became our reference and parameters for what’s possible for us. In Southeast Asia particularly, the role model of a woman being valued chiefly as wife and mother continues to cause inner conflict within modern women. My mom was and still is a homemaker, and her life has been an epitome of self-sacrifice for her family and children. Her example and influence set a high bar for motherhood that I continue to find difficulty reconciling with my professional aspirations. Despite the progress made in education where girls and women are now more educated in more Southeast Asian countries, we continue to struggle between our personal aspirations and the examples set by our primary role models in life.

What motivated you to fight for women’s rights and equality? How are you bringing your own experience of healing to help other women in Asia?

I came across the issue of female infanticide during a volunteer trip to India in 2007 at an orphanage called Aarti Home in Kadapa. It pained me greatly that girls were not given a chance to live simply because they are girls. When the NGO helped the village women gain skills to make a livelihood, it helped the mothers to change their decision. I saw the power that financial independence gave to women to change their lives.

With hindsight, I realise that the extreme discrimination I saw encountered by girls and women in India resonated with a part of me that was hurting from having grown up in a household which held conservative and patriarchal values. I felt greatly privileged that I could have an education and a career to forge a future of my own, despite struggling with the inner conflict that society and upbringing has created in me about what women should and shouldn’t do or be.

In the beginning, I was moved by a sense of anger and injustice. It provided the drive and fuel for starting Daughters of Tomorrow to uplift women through confidence-building, skills and jobs. However, change was limited and slow as I met roadblocks attempting to influence and mobilise resources that could help underprivileged women in Singapore.

I remember speaking to corporates and donors about poverty in Singapore, and people were uncomfortable when you approach the conversation with indignance and anger. This prompted me to reflect on my own anger and self-righteousness and helped transform my advocacy approach from confrontation to collaboration, from “fighting against” to “forging with,” inspiring and catalysing allyship between women and men to advance the cause of women’s empowerment together.

According to an OECD study, around 25% of women in Southeast Asia have suffered physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner. What do you think needs to be done to tackle domestic violence against women?

The cycle of pain that exists in families, suffered by women of the past and witnessed by children of the present will continue to perpetuate itself unless we manage to break the cycle. Everything stems from love, and if as children, someone grows up learning that love meant enduring pain and abuse “for the greater good,” that’s how someone will continue to unconsciously gravitate towards relationships that are abusive, because that’s the model of love that they are familiar with. In the same way that boys exposed to dads who disrespect or dominate over women will learn that that’s the “right way” to be a man.

How is the progress made by Southeast Asian governments in reforms and policies granting women equal rights hindered by existing familial, cultural and societal norms?

Laws and policy reforms could be made but if mindsets of individuals continue to be based on operating within the familiar, the changes are cosmetic and artificial. Hence in Southeast Asian societies where people’s lives have been guided by their faiths and religions for centuries, policies will always run up against more deeply entrenched religious and cultural beliefs and norms in their attempts to forge change.

Governments need to work closely with religious and cultural influencers and stakeholders, and engage their allyship in grassroots education that aligns and draws from religious and cultural teachings that align with strengthening respect for women.

Where do you think Singapore sits on the global scale of women’s rights and freedom?

More women than men are graduating from university these days, and workforce participation by women has grown over the years. Of course there is still room for improvement, and we have dedicated 2021 as the year of women’s development, with commitment by the government to enhance our policies to better protect, as well as support women.

At the national level, there haves been continual efforts to improve maternity and caregiving support policies in order to reduce the conflict between care and career. Socially, we still have some way to go but I’ve been observing more dads taking on more active role in childcare and elderly care, which helps to equalise the distribution of care.

What do you think the government can do to tackle issues of women’s rights, safety and equality in the city-state?

Since my election into Parliament in 2020, I have been championing the ungendering of care. This includes enhancing paternity leave provisions, providing more financial support to caregivers who are mostly women, and enhancing ageing care in the community. These policies are important as caregiving has been, and will continue to present, significant barriers and obstacles to women’s participation in the workforce, and in all leadership spheres as our society ages.

There are differing views within Singapore society on abortion, as on many other issues. But the good thing is that our laws and policies in Singapore are kept very separate and clear away from any religious or moralistic ideology or influence, our government is very careful about that. Pragmatism underpins our policy-making and is a principle that has worked to keep our country an inclusive one.

What do the recent anti-feminism protests in South Korea say about Asian attitudes to women’s rights?

Any movement that calls for change in any given manner will invite a response logical and appropriate to that manner. A movement stemming from anger will invite anger in response.

Peaceful and gradual change-making is the key to forging change that can be accepted by the mainstream, bearing in mind that too much uncertainty too fast will cause people to feel under threat and invite a corresponding response.

The protests in South Korea, from both feminists and anti-feminists show us how much bottled up anger and pain there are, in both men and women. Women suffer from the oppression of patriarchy that has existed over centuries. Korean men are also suffering from the pressures of breadwinning and being providers to their family, upheld by the same patriarchal notions. This situation may have been exacerbated by other conditions such as economic recession.

How are you using your experience working for women’s rights and equality in Singapore to help women and men in South Korea?

I am bringing workshops on self-awareness, personal healing and transformation to South Korea, to help people understand their own suffering, and to liberate them from anger and conflict within themselves.

I am bringing my healer and teacher Hun Ming Kwang to Seoul, and making workshops available to anyone who wishes to change their lives and liberate themselves, especially for changemakers who aspire to create positive change in society. We want to create a momentum for peaceful and powerful social change by giving changemakers the skills and knowledge they need to run transformative movements built upon collaboration and allyship.

This project is important to me as I learnt that we can all heal, and that in our healing, we become positives forces for change to those closest to us, and to causes we dedicate our hearts to serve. As a transformative coach and healer, it is my duty to bring healing where there is pain. As a peace advocate, I go where there is conflict to advocate peace. As a gender equality champion, I go where balance is needed for the genders to come together in equality.

What is your main hope for the future of women’s rights in Asia?

That women and men discover that their common enemy is patriarchy, and not each other. With this understanding, they come together in support and allyship for one another, as a pair of wings working together towards actualising our highest potential.