Nearly a decade ago, Cambodia’s Land Ministry introduced plans for a new capital city that were as opulent as they were otherworldly. The grand proposal was erected at a technology conference, where an entire gallery was filled with plastic towers built in the image of a brand new, futuristic Cambodia: bright blue and green towers stretched their silver spires toward the conference room ceiling, their glossy finish reflecting the dingy incandescent light of the bulbs shining overhead.

This was the public’s first glimpse of the “Dragon City”, laid out in all its plastic-and-cardboard glory, and many were in awe. “Phnom Penh will look like New York by 2025!” exulted one excited viewer, sharing his reaction on an internet forum in December 2010. The project designers put out a call for a staggering $80 billion in investment to build the new capital. At the time, Cambodia’s gross domestic product was just $11.24 billion.

A curious mix of Angkor Wat-like construction – complete with moats and galleries laid out in the sacred geometry of Hindu antiquity – as well as the sweeping roofs of ancient Chinese architecture, the project was named “Samdech Techo Hun Sen Dragon City” in honour of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s royal title and zodiac sign. Nevertheless, even in its most nascent form the city appeared to stand as a glittering homage to China – and, in that respect as in many others, little has changed over the past nine years.

“We want to do this project as a dual investment between Cambodia and China,” said Phuoeng Sophean, secretary of state for the Land Ministry and the brains behind the Dragon City project, speaking loudly into the phone receiver as static crackled over the line. “To support our country, we need big companies and the Chinese state involved, people who want to realise this idea.”

“It’s hard to explain to you over the phone,” Sophean shouted. “Can we meet in person?”

Sophean is a slight man in his early sixties; his walk was a slow-paced shuffle across the floor of the Phnom Penh cafe, stacks of notes and project ideas dating back almost a decade clutched in hand. With him was a hefty portfolio dedicated to the as-yet undeveloped Dragon City, the cover decorated in a collage of curated photos. A futuristic spire cut the cover in half – Prime Minister Hun Sen smiling to the left of it, and Chinese President Xi Jinping beaming to the right.

“This is my project,” Sophean said. “We know that in Phnom Penh now, there is a lot of traffic, this is a very important problem –” he paused, taking a moment to wave at the stream of honking cars and tuk tuks crawling past the cafe window, “and at the same time, Phnom Penh is an old city… we need to think about the development of a new city.”

He took out his pen as he spoke, sketching a bird’s eye view of the city, complete with cordoned sections: twin towers in the heart of the business district, an education sector in the south, residences in the north. “We need this land to make a new city, because there is fresh air, new [forms of] communication, new transportation underground – we can [create] a subway or metro, like in Europe,” he added. “[We will] have different sectors of the city where there are different activities… [like] administration, business and residential sections.”

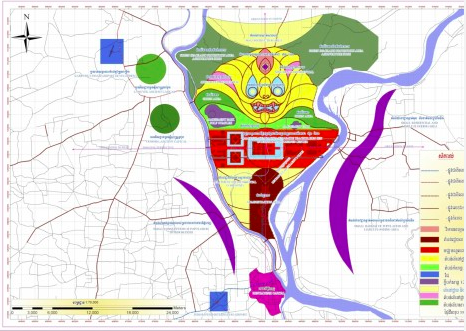

Many of the words Sophean used to describe his project could have been lifted from a script, so similar were they to the quotes given to other media outlets over the course of nearly a decade. He ran through the same history lesson, listing Cambodia’s ancient cities and the kings who built them, and lamented the fact that no new city had been built in the Kingdom since the fourteenth century. He described the 600-metre tall building – which, if built, would be the fourth tallest in the world – that would serve as Hun Sen’s headquarters at the heart of the new city. And he gave the same description of his vision to see the city take the literal shape of a naga, to be sculpted from expertly-placed, brightly illuminated buildings, so that all who fly over the city can recognise the shape of the Cambodian dragon.

“When we fly from any country and we go through this way, we can see the head of the naga, and we can say this is Cambodia.”

Phuoeng Sophean

“When we fly from any country and we go through this way, we can see the head of the naga, and we can say this is Cambodia,” Sophean said, drinking green tea in Java Cafe last week. “When you fly into Cambodia, you will see the lights like the head of a naga, and you will know you are in Cambodia,” Sophean told the Cambodia Daily six years ago, in a 2013 interview.

The basic concept of Dragon City, then, has largely remained the same, but the land on which it is intended to be built – a vast 35,000-hectare swathe of territory north of Chroy Changvar on the east bank of the Tonle Sap River – has steadily seen greater amounts of development. It is by no means packed with as many skyscrapers and businesses as in the heart of the capital: the land is still home to pastures, clumps of trees, and cows lining the roads. But so too is it home to smatterings of construction sites, multiple luxurious buildings, and the residences of hundreds of locals.

Driving through the Chroy Changvar countryside, the cars are fewer but faster. Though billboards advertise for new, luxurious villas and residences, the land is overwhelmingly local – a haven from the high living costs of Phnom Penh for people who want to live and work close to the capital. The newly developed “Win-Win Monument”, unveiled late last year as a place for Cambodians to, in Hun Sen’s words, “research, relax, exercise or do whatever they want”, stands in the heart of Chroy Changvar as a $12 million testament to near-abandonment. Locals man the empty parking lot, while a sole vendor sleeps, his drinks and snacks unsold.

When asked if they had ever heard of a proposed “Dragon City”, ten different locals looked confused, shaking their heads back and forth. “Ot sgoal,” they repeated. “I don’t know it.”

“The Ministry of Wildlife and Fisheries used to be responsible for this land, but now some Oknha who are rich have come to set up some new residences here, which cuts into the land [intended for Dragon City],” Sophean explained, referring to the title awarded to wealthy tycoons who have made a substantial donation to the Cambodian government. But the city can still be built around these residences, he said. And locals should not stand as an impediment to building either, thanks to a government policy that allows the state to nullify locals’ claims to their land; officials can pay property owners the same amount for which they bought their land and force them to vacate the premises in advance of building, he explained.

Though there are currently three Chinese companies – which he declined to name – interested in investing in the city, Sophean said that there have been difficulties in getting the Chinese government on board with the project as it is not yet “attractive” enough. The $80-billion price tag for the development remains the same, and though Cambodia’s annual GDP has nearly doubled in the past nine years, it still amounts to barely a quarter of the proposed investment. “I know… $80 billion is a lot,” Sophean admitted. “[But] my idea is to make this city look like an international city, with [changed] laws… a new law for a new city.”

His concept for attracting investment essentially relies on selling off Cambodian land. Thanks to the Kingdom’s Foreign Ownership Property Law, foreigners cannot technically own plots of land, and are largely limited to co-ownership of residential buildings. But Sophean would have this change, encouraging foreigners to invest by baiting them with ownership of their own land in Dragon City – and with the Chinese state as one of Sophean’s main target audiences, the prospect is a dangerous one, as it could see great chunks of Cambodian land legitimately owned by the Chinese government.

But there has been no talk of changing the foreign ownership law as of yet, according to Phay Siphan, spokesman for the Cambodian Council of Ministers. “Well, I mean from my understanding, we don’t have plans to amend any law at all, I don’t see anything about that,” he said over the phone. When asked if he knew about the Dragon City project, he responded with confusion. “What city?” he asked. “I don’t know about it… it sounds like a businessman trying to promote an idea to sell the property. I don’t count on it.”

He added that the proposed location for the massive city has already been slated for development by other companies, some Chinese and others Cambodian. “I say that Dragon City is not happening,” he said, pausing before adding further clarification. “I mean, not in that area, at least.”

Dragon City has long had its naysayers and disbelievers, and Stephen Higgins – a current managing partner at Mekong Strategic Partners, who in 2009 was quoted as CEO of ANZ Bank saying that he would not loan money to people looking to purchase property in satellite cities around the capital – has long been in the camp that deems the building of the city an impossible task.

“A project like this was not feasible nine years ago, and it’s not feasible today,” he wrote in an email this week. “[And] it’s clearly not in Cambodia’s interest to have a city anywhere that is geared principally to foreigners.”

But while Dragon City itself may be an unlikely project, Anthony Galliano, the CEO of Cambodian Investment Management, explained that it would eventually be necessary for Phnom Penh’s bustling population to spill into areas like Chroy Changvar, and that investment in the lands surrounding the capital is an inevitability.

“The ambitious Dragon City project remains on the drawing board and will likely remain so in the near future,” he wrote in an email. “However, it will be an eventuality given the population growth, migration of people from the countryside to the city, and influx of Chinese nationals.”

Galliano said that although the Kingdom is “feverishly embracing” what appears to be an “unending supply” of Chinese investment, Cambodia could be losing its grip on its own autonomy as more and more money pours in.

“Besides wielding its economic prowess, China is also infiltrating Cambodia through populating it with its nationals,” Galliano wrote. “While financial flows are mobile, people are permanent, thus allowing China to have long lasting clout.”

While the glittering spires of an imagined Dragon City are losing their shine, a new future is taking shape in their stead: one in which satellite cities around Cambodia’s capital are grown on the back of Chinese investment and even – if Sophean gets his way – on the enticing promise of legitimate foreign ownership of what was once Cambodian land.

Sophean’s hand shook slightly as he lifted his tea cup to his mouth, and continued to tremble as he returned it to its saucer.

“We must have the relationship form between China and Cambodia first,” he said, trying to explain his vision. “[We must] focus first on China, because now, the relationship with China is very strong. We can also cooperate with Japanese or European companies, no problem…”

He paused, his tea cup making the slow pilgrimage to his lips.

“But China is better.”