Walking around the riverside venues of Phnom Penh, it would be easy to miss the Good Times Bar. About 20 people squeezed into the sweaty, narrow venue barely a few metres wide, watching as the band does a sound check on a stage barely big enough for the musicians.

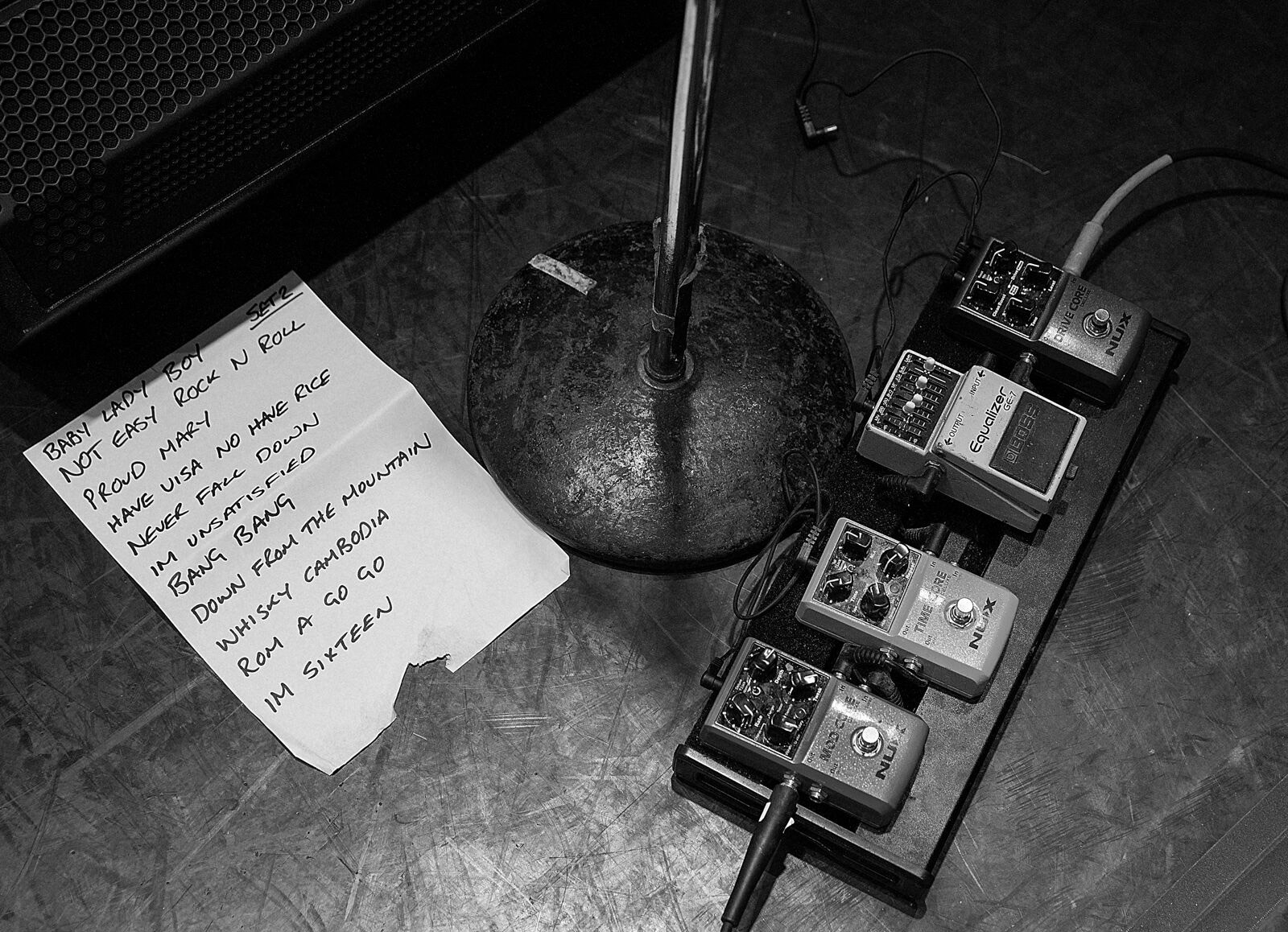

That night, the Cambodian Space Project (CSP), hailed for rejuvenating the “golden era” of Cambodian rock-and-roll, took to the smallest stage in Phnom Penh to pay tribute to their late enigmatic front lady and co-creator, Kak Channthy.

Cambodia’s ‘Edith Piaf’ of the rice fields, Channthy was tragically killed in a traffic accident in Phnom Penh on March 20 2018. At 38, she had become a household name across Cambodia, leaving behind an influential musical legacy, remembered for her unique voice and fearless personality.

“She was a force of nature. She was somebody who embodies and epitomised all that is Cambodia herself,” Julien Poulson, co-creator of CSP, told the Southeast Asia Globe at a cafe in Phnom Penh, the night after the gig. “She was somebody of great beauty, but on the other side, had come from bitter, brutal hardship.” Poulson and Channthy had married in 2010, but their relationship eventually ended in a bitter divorce marked by disagreement years later.

Reviving the nostalgia for Cambodia’s lost divas and rock legends, CSP toured the globe spreading Cambodian music, collaborating with the likes of Australian musician Paul Kelly and American Dennis Coffey.

For six years CSP toured venues around Cambodia, to music festivals and theatres across Asia, Europe, Australia and the US spreading their vibrant live performances. CSP also pressed Cambodia’s first post-Khmer Rouge genocide vinyl record.

But Channthy’s unlikely success was not always easy rock ‘n’ roll. Despite her infectious and happy persona, close friend of Channthy, Sopheak Sao, said her life was full of hardship from the beginning. Raised in extreme poverty, she also faced family violence at the hands of her loved ones.

Channthy took the leadership, she fed them, protected them and provided for them. Everything

Sopheak Sao

“Her father was a heavy drinker and domestically violent … She was also married before [Poulson] to a Cambodian, who she had her son with, but he was also very violent,” Sao explained. “She started with nothing and raised not only her son but the whole family, until her mother and father passed away.”

In a dominant patriarchal society, Channthy smashed Cambodian gender roles by being the main breadwinner for her family. “She took the leadership, she fed them, protected them and provided for them. Everything,” Sao added.

Channthy was born in 1980, a year after the Khmer Rouge had been overthrown by Vietnamese troops, in a farming village in Prey Veng province. “She was born in the conflict zones. There was guerrilla warfare, so if you were in that environment you were on the front line,” Poulson said, explaining that warfare and famine had ravaged families.

Poulson said Channthy would often joke about the timing of her birth. “She’d say, ‘Ahh when I was born, Pol Pot, he hit the road! He ran away, Channthy is coming!’”

Channthy had lost two older brothers to famine, making her the eldest child, and so responsibility for her family’s well being fell on her from a young age. Only completing three years of school, she had to work to support her impoverished family, taking arduous and often dangerous jobs on rubber plantations and rice fields.

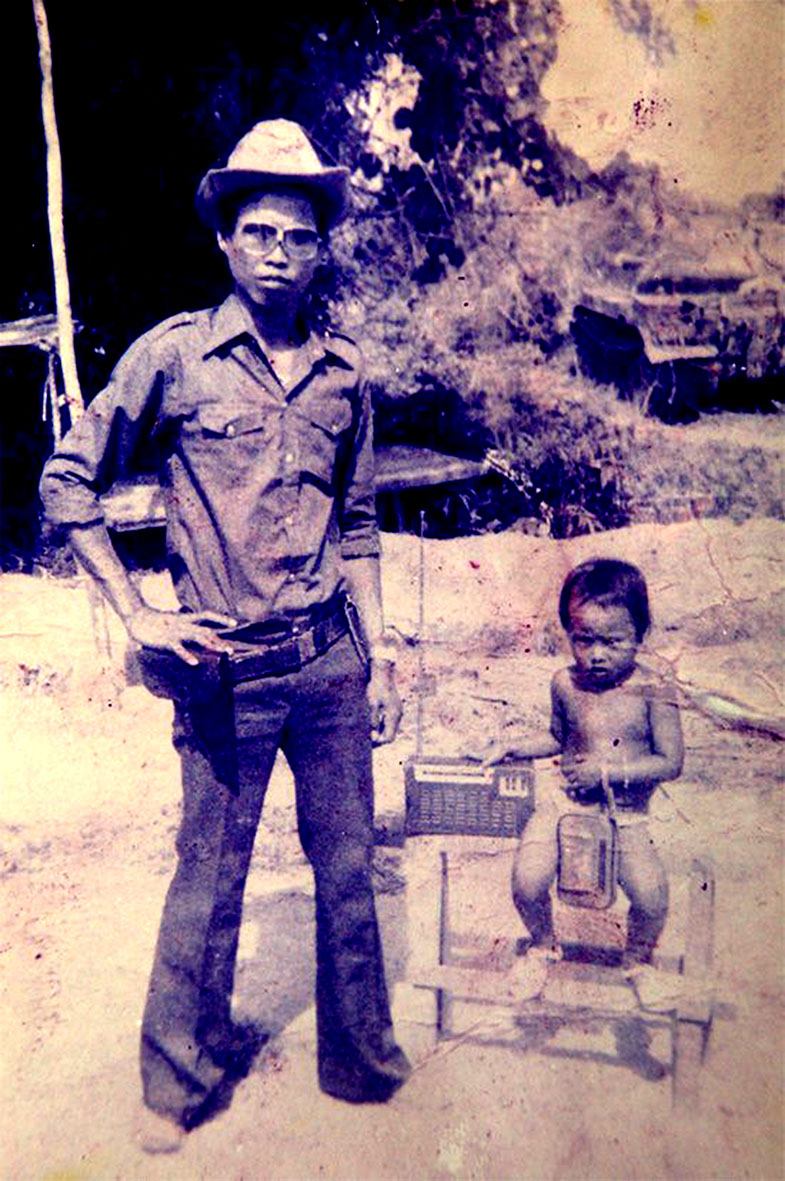

On a visit to her parent’s village in 2009, Poulson noticed a photo of Channthy and her father taken when she was three years old, pinned to the wall of their bamboo hut. In the background, a T-55 army tank can be seen blending into the jungle. And between them, sits a little transistor radio.

“You look at and think wow, what were they listening to? Was is Cambodian rock-and-roll? Who knows,” Poulson speculated. “But tuning into signals from far away became a theme of Channthy, and who she was. She was always wanting to understand the world out there and music was always a part of that.”

Before the Khmer Rouge, music in the Kingdom had thrived. Fostered by a young Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the 1960s ushered in a cultural revolution across Cambodian society post-French independence in 1953 – from architecture to art and music.

Hailed as the “golden era” of Cambodian rock-and-roll, the ‘60s and early ‘70s flourished as a hybrid mix of Western surf pop and psychedelic rock melded together with traditional Khmer rhythms to create a unique musical sound. Influenced by US army radio provided for troops stationed in Vietnam, Cambodian artists like Ros Sereysothea, Sinn Sisamouth and Pan Ron were celebrated for mixing Cambodian music over Western soul and pop-rock.

Even as the Cambodian civil war between 1970-75 gripped the nation, the music scene persevered until the Khmer Rouge took control in 1975, ushering in a four-year rule in which a quarter of the population perished in forced labour camps and prisons. Artists, intellectuals and singers were targeted, exiled or killed under the regime, with many of their fates still unknown.

It took decades for Cambodian rock ‘n’ roll to rear its head above the rubble, and it wasn’t until one night in 2009, when Poulson met Channthy, that its mini rebirth began.

Channthy was working at a karaoke bar in Phnom Penh for $2 a day when Poulson heard her sing. “[Channthy] sang the Khmer version of Peggy Lee’s Johnny Guitar. It was just haunting and powerful in that setting, and I could see the strength in her doing this.”

He knew at that moment he wanted to form a band. They began jamming at different bars around Phnom Penh, with Poulson on guitar and Channthy as lead vocals, before eventually forming CSP and later getting married.

At first CSP covered Cambodian golden-age classics of Sisamouth, Sereysothea and Ron, always adding their own psychedelic funk into the mix. Despite being illiterate, Channthy began writing her own music, with hits like “Whiskey Cambodia” and “Have Visa No Have Rice” reflecting upon her personal experiences as she adjusted to fame.

The language barrier was always a hurdle for the duo as Sao recalled. “I remember once, early on, Julien was trying to tell Channthy ‘I love you, I want to be with you. Would you be with me?’” Sao said, adding that Julien asked her to translate. “Instead of answering the question, Channthy said, ‘Well, my father needs a generator, can you buy it for him?’” Sao laughed. “In the end, she got the generator!”

The nostalgia of Cambodian rock combined with Channthy’s life story was a powerful mix, which did not escape the notice of German documentary filmmaker Marc Eberle. His film Not Easy Rock and Roll, released in 2015, followed CSP, as well as Channthy and Poulson’s tumultuous relationship, for six years.

Eberle saw Channthy’s transformation first-hand as he followed the band throughout the world. Meeting them at a gig in Phnom Penh just three weeks after they formed, Eberle realised “then and there, it was going to be a great story”.

“She was a positive story coming out of Cambodia,” Eberle explained. “Cambodia was only known for Angkor Wat and the genocide. And now because of Channthy, [Cambodia] is known for music.”

Eberle said Channthy became a much loved Cambodian icon, whose humble beginnings meant she was able to tap into the Cambodian pulse. “We should celebrate her and appreciate her for making this happen and making this story of Cambodia out of her own beauty and talent.”

Throughout the documentary, Channthy was able to open up for the first time about family and life traumas, Eberle describing the filming as often turning into a counselling session.

“If I look back now, [Channthy] was opening up because she really needed help with her life and she didn’t know how to deal with this barang guy, Julien, suddenly having an interest in her,” Eberle said, using the Khmer slang for foreigner. “But she was very much empowered from the get-go, she knew the game.”

Her ability to loosen the shackles of her role as a Cambodian woman took years, Eberle explained. “We’d tell her, ‘you gotta be empowered and powerful and strong’, and she’d go ‘No, in Cambodia we’re not like that.

She is a role model and a true Cambodian artist. She never gave up, nor her family or her own self. She put other people first and put her family first. She was very loved by everyone, even her father, who was violent to her. She helped him, and I think he appreciated that later on

Sopheak Sao

In the end, Eberle said Channthy was seen as a strong feminine figure and had the musical talent to back it up. “Given what she was learning and how fast she was changing, was incredible to witness for me.” Eberle described her life as an oncoming storm, saying he felt grateful to have not only made the film, but be a close friend throughout.

By 2016, Channthy had split from Poulson and CSP, and started her own band with Australian songwriter Scott Bywater, called Channthy Cha Cha.

However, on March 20, 2018, Channthy’s life was tragically cut short. The auto-rickshaw she had been travelling in with her partner at the time was struck by a car in Phnom Penh.

Sao remembers feeling disbelief at the news. “I tried to call her family, I even tried calling her five times … For two weeks I couldn’t go out [of the house], my husband took care of me.”

“I will never forget her,” Sao said. “She is a role model and a true Cambodian artist. She never gave up, nor her family or her own self. She put other people first and put her family first. She was very loved by everyone, even her father, who was violent to her. She helped him, and I think he appreciated that later on.”

A selection of images from Channthy’s funeral. Middle-right, a picture of a set list from a Cambodian Space Project gig. Photos: Steve Porte

“I miss her very, very much,” Sao said.

Channthy’s death reverberated around the world, even rock legend Iggy Pop paid tribute. “I am so, so sorry to hear about the tragic passing of the beautiful, charming and totally unique Channthy,” the Detroit rocker said.

“The outpouring of grief after she died was for the first time really showing the resonance she had in this community that she’d built and kept together; she was at the centre,” Eberle said. “When historians look back at the big names of the era Channthy will be one of them.”

Poulson saw Channthy as an international phenomena, saying he felt that she would live to old age and be the grand old dame of the rice fields.

“I saw Channthy, having come right out of the quagmire of civil war and abject poverty, was a phenomenal story,” he said. “And that story and her voice became the story of a whole nation, one that will probably only be understood in generations to come.”