Photography book remembers Cambodian refugee resettlement in Chicago

Photographer Stuart Isett spent three years photographing Chicago's small Cambodian community in the early 90s. Thirty years later, his photos are resurfacing in a new book drawing attention back to a little-remembered generation of Cambodian-Americans in the US

All images by Stuart Isett.

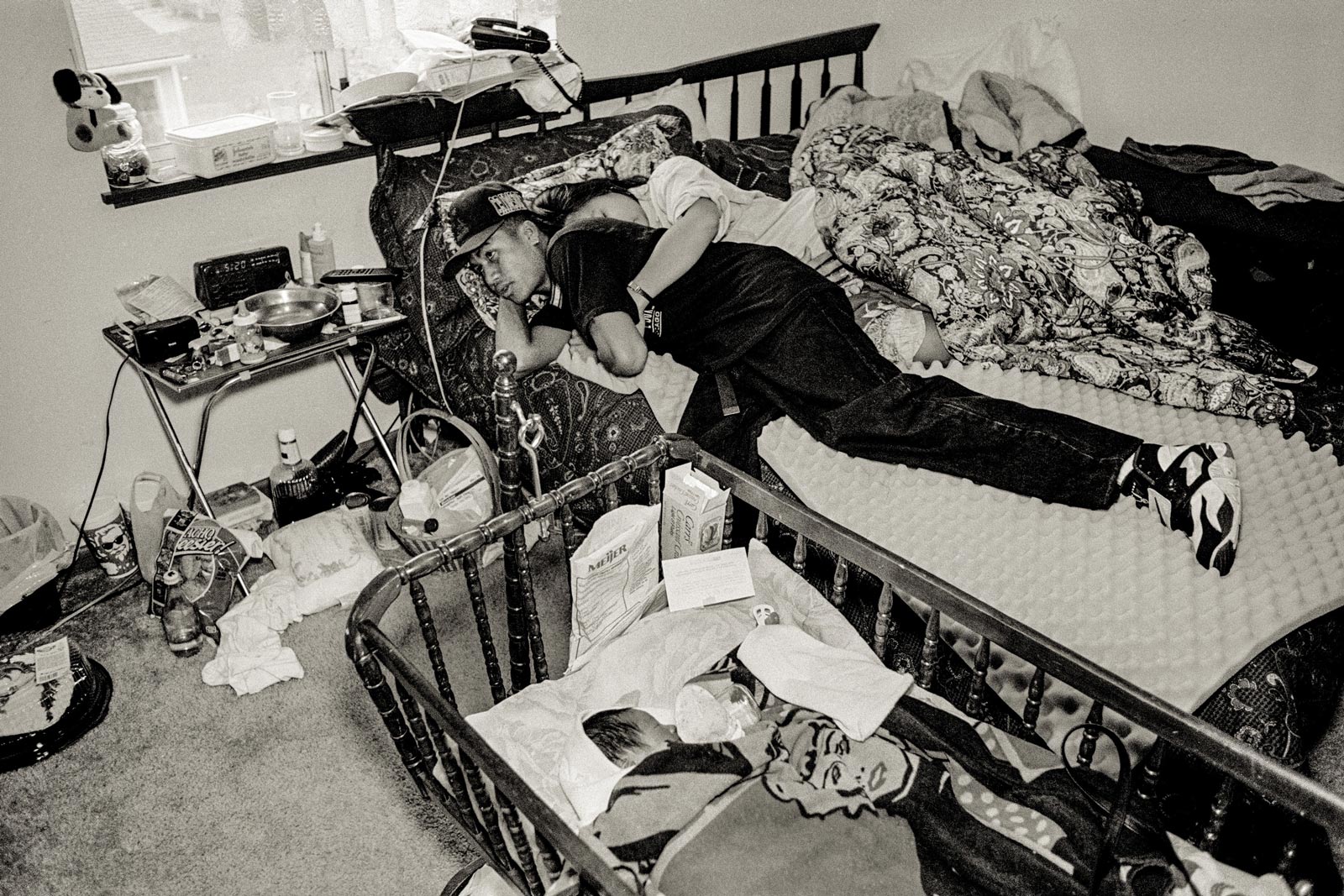

Wendy wore a princess dress for her third birthday. Seconds before the photo, she’d been playing, dancing around the room the way toddlers do. This was before her older brother Ricky, a teenager, had snapped at her to stop. His tired expression is apparent as he lays on bed beside her.

The photo encapsulates the intergenerational differences between Cambodian refugees when they settled in the US in the 80s and 90s.

US photographer Stuart Isett spent three years with the recently resettled Cambodian community in his hometown of Chicago from 1991 to 1994. In what was initially a Master’s thesis, Isett saw the older teens who would hang in the back of the Cambodian temple after being dragged there by their families. After spending time photographing Cambodian refugee camps in Thailand in the 80s, he was drawn to the group because of his familiarity with what they were fleeing.

When Cambodian-American Photographer Pete Pin was looking for photographs from this time period, he found Isett’s work from the early 90s and reached out. Along with Silong Chhun, a Cambodian-American multimedia artist and activist, the three wrote, edited, and sequenced Isett’s photos in On the Corners of Argyle and Glenwood – a soon-to-be-released photography book.

Pin himself was born in a refugee camp on the Thai Cambodian border, and Chhun was born in 1979 in Cambodia. Both resettled in the US in the early 80s.

“Those pictures don’t exist anywhere [else],” Pin told the Globe. “There’s no record of the Cambodian community in that initial wave of resettlement in the US.”

A note from Stuart Isett: This photograph shows Gino and his mom on their back porch in Chicago. Gino had lived in the cities of Bakersfield and Long Beach, California, but his mother sent him to Chicago after he was shot in a gang fight. Gino then lived with his sister at the corner of Argyle and Glenwood. In 1993, Gino and I flew out to California, spent a week or so out there and then we drove his parents back to live in Chicago with the rest of the family. This was the night we got back to Chicago after four days of driving. There was a small gathering at his home to celebrate his parents’ arrival, and Gino’s mom walked out on the back deck and gave Gino a huge hug.

I spent a lot of time with Gino over the three years I worked on this project; he projected a tough exterior but was a really sweet guy, very kind and generous with me, always letting me tag along and take my photographs. He really was the anchor for much of what I was able to do. This photo reminds me of his kindness and where he got it from – his mom.

Between 1975-80, about 130,000 Cambodians refugees arrived in the US after fleeing Khmer Rouge rule. After leaving Cambodia, many waited in refugee camps in Thailand before being sponsored by American families and organisations to resettle in the US.

“I was fascinated to find out how you could live through this experience and wind up in this country [the US] and what would happen,” Isett told the Globe.

He says most Cambodians in Chicago were living in a few buildings at the street corner he documented, Argyle Street and Glenwood Avenue, which lay within a part of uptown Chicago occasionally labelled “New Chinatown” or “Little Saigon”, inspired by the communities of Asian immigrants who settled there from the 1960s.

They struggled with language, they struggled with education, they wound up getting involved with gangs

Cambodians, then and now, made up one of the smaller pieces of the Asian American tapestry. But their experiences in the US were distinct from other Asian American groups, marked by the deep trauma of their homeland and resettlement. The diasporic experience in Chicago was one Isett described as branded with an intergenerational sadness.

“The older they were, the sadder they were,” Isett said.

Older adults, under pressure to preserve the family unit after immense trauma, were nearly “catatonic”, as Isett describes. Older children struggled to adapt, some banding together on the streets in a bid to protect themselves and their communities from crime in the cities.

“The sixteen, seventeen, eighteen-year-old kids arrived here a lot older and had huge problems adjusting. They struggled with language, they struggled with education, they wound up getting involved with gangs,” Isett said.

In the early 1990s, when gangs, drugs, and guns were especially rampant across US inner-cities, Pin says it was expected for young Cambodian men to gather for protection after being thrown into such an alien environment. This speaks to the systemic issues Cambodians faced when moving to the US – from facing a new education system and the bullying that came with it, to living with the trauma they’d experienced in Cambodia. As the targets of discrimination and policing, these young men faced significant barriers to integrating into their new country.

With discrimination, poverty and brutality defining their lives in the US, many of these young men formed protective street gangs in Cambodian communities around the country. In Chicago, in response to attacks from local gangs, about 30 to 40 young Cambodian men formed a group of their own called the Loco Boyz – just one of many Cambodian street gangs nationwide.

Despite decades passing, Pin said that he remembered his fear of this generation of Khmer men when he looked at Isset’s photos.

“I was afraid as hell as a kid of those guys. They were hard as hell,” the now-39-year-old said. “They had to be hard.”

Isett emphasises that this gang culture was a response to pre-existing issues in the US, namely the prevalence of gun violence and weak policing. Inevitably, gang life resulted in many ending up in jail, while other Cambodians with more precarious immigration status in the US were deported back to their homeland.

Since 2002, at least 998 Cambodians have been deported from the US and repatriated to Cambodia for breaking laws as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act passed in 1996 – 733 of them initially arrived in the US as refugees. Some are returning to a country they’ve never been to after being born in refugee camps in Thailand, or one they don’t remember after living in the US most of their life.

Isett and Pin both say there’s a lot of shame in the Cambodian-American community surrounding gangs, and Pin has faced pushback when attempting to photograph it. Pin says Isett’s photos don’t show a moral failure of these young Cambodian men, with their situation exacerbated by trauma, poverty, racism, and systemic issues in policing and violence.

“It wasn’t anyone’s fault. It was just the way it was in the 80s and the 90s,” Pin said.

Much of the turmoil these new Americans faced went, at the time, largely unnoticed by mainstream society. Until Pin and Chhun’s generation came of age, there was little work done to shed light on the Cambodian experience, neither in Southeast Asia nor in the US.

Isett’s photos from Chicago were published in magazines around Asia, but found very little interest in the US. In fact, Isett was frustrated when many of his peers, including those in his graduate programme, couldn’t find Cambodia on a map. He compares it to a black hole in history.

“I’m going, ‘Jesus Christ, we just spent half our national treasury flattening these countries with bombs.’ They knew Vietnam, that was it,” he said. “Cambodia, it was called the sideshow.”

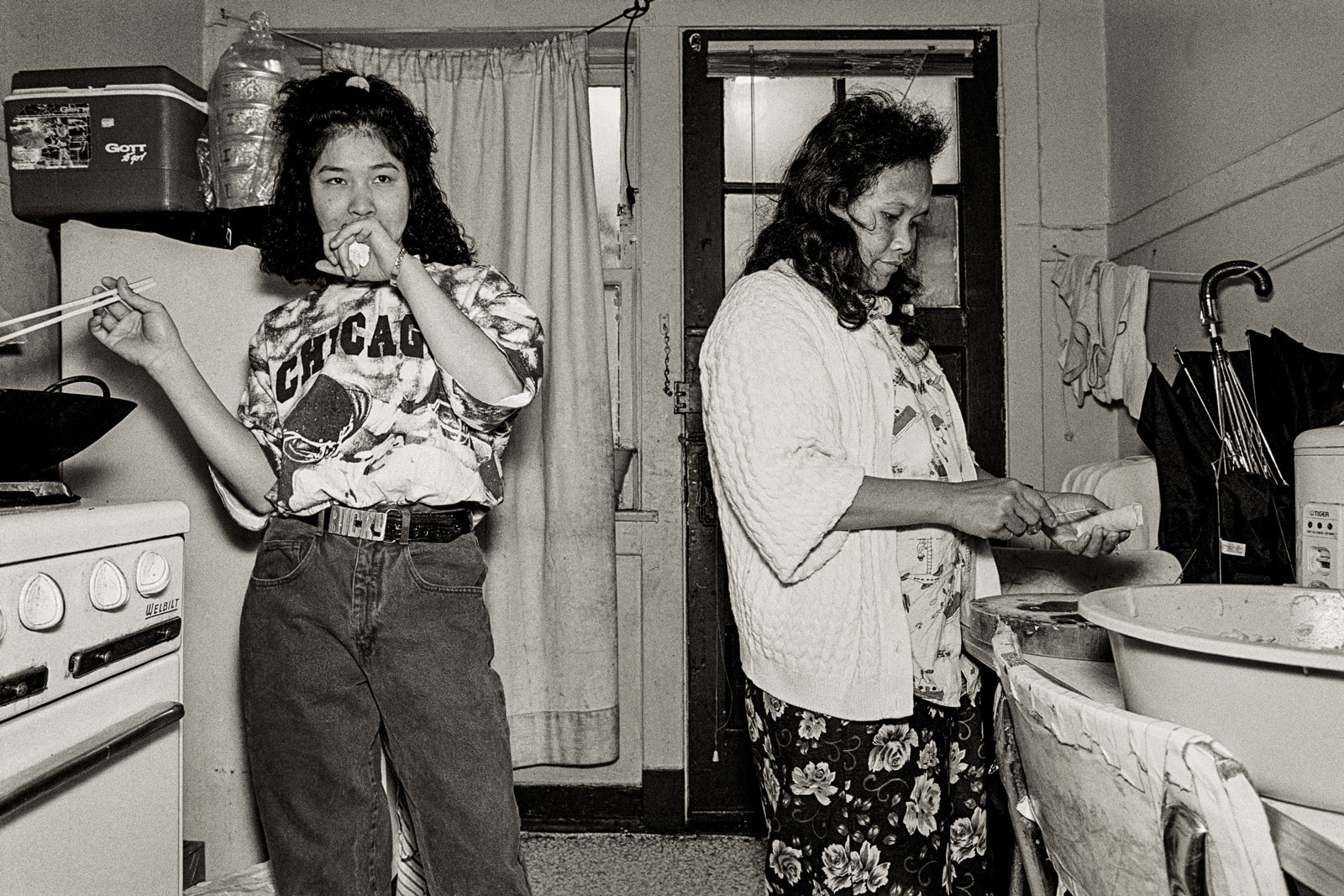

Isett describes Pin and Chhun, both now in their late thirties, as the younger siblings of the teens his work focused on. Though his work centered on older teenage boys, many of the scenes he pictured are in family settings, capturing the daily life of the community and its households.

“A lot of those experiences, a lot of those homes, a lot of the interiors, the people, the dress, all that was just very very familiar to me and Silong,” Pin said.

That doesn’t mean the children had it more straightforward than the adults, and there were many incidents of children getting bullied and picked on during school for being who they are in a new country. It wasn’t easy for any of us

But the experience of immigration was different for each generation. Chhun says children had the opportunity to learn English in school, while parents were saddled with the responsibility of caring for a family and finding work in an unfamiliar country, all while coping with the trauma of the war.

“That doesn’t mean the children had it more straightforward than the adults, and there were many incidents of children getting bullied and picked on during school for being who they are in a new country. It wasn’t easy for any of us,” Chhun said.

Isett says the story of Cambodians just didn’t register with Americans, who didn’t differentiate them from other groups of Southeast Asian immigrants, and therefore couldn’t provide the support they needed.

“It’s like ‘Welcome to America, here are the keys, good luck,” Isett said of their resettlement.

Chhun says Isett’s photos hold great value as they preserve a precise time in Cambodian-American history, when refugees were finding their place in the US.

“It is crucial because, under the Khmer Rouge, the values of family photos of the past were the only tangible piece of history that families had after losing everything,” Chhun said. “These photos by Stuart give us a glimpse of what life was like as a Cambodian refugee struggling to find a place in the new world.”

On the Corners of Argyle and Glenwood, published by Catfish Books, can be pre-ordered here.