It was a hot and humid late Sunday evening on February 10, 1991 in Battambang, a northwestern province of Cambodia, where the devastating Cambodian armed conflict between the ruling State of Cambodia (SOC) and the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) – the coalition resistance forces of the Khmer Rouge, the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (KPNLF) and the FUNCINPEC – was ongoing.

My family and I were having dinner. Our meal that evening, however, was extraordinary as the situation abruptly became too dangerous for everyone to finish eating. The first artillery shell landed and exploded within a very close range shaking the ground of my village. Every family member stopped talking and carefully paid attention to what was going on outside. Yet, it was still quiet. During wartime, Battambang was a critical theatre of military operations and such an explosion was common in everyday life. By then, we assumed that nothing had happened – it was a fatal assumption.

The Khmer Rouge’s ground intelligence officer might have taken that short moment to confirm the first hit, with none of my fellow villagers anticipating that our village had already been locked on target by their artillery unit. A few minutes later, I heard the second explosion followed by hundreds more before realising that my village had come under artillery bombardment by the Khmer Rouge armed forces.

Thousands of pieces of shrapnel fell on the roof of my house and sounded like a downpour. The canal running in front of the houses in the village became a bunker sheltering my family and other villagers from the ongoing artillery shelling. Women and children started screaming and crying.

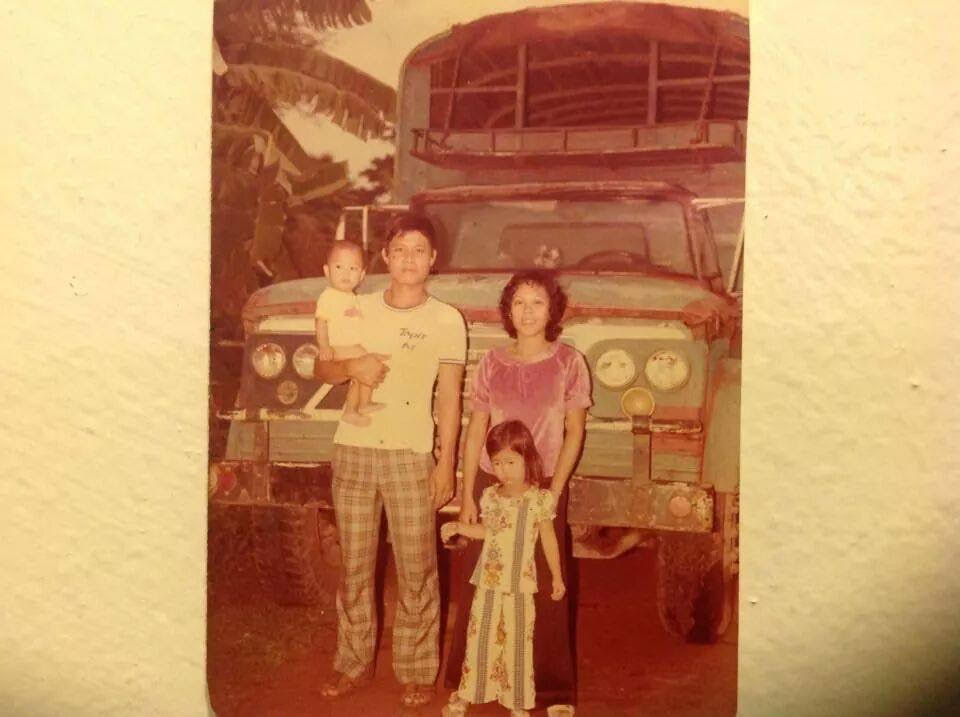

Some parts of the village were quickly set on fire. In panic, I heard a series of painful voices due to injuries. That was the moment I felt that time was standing still, while the Khmer Rouge’s massive artillery shelling continued for about an hour before retreating back to their base in the darkness of the night. My dad drove a truck to evacuate us from the burning village and we did not come back to our village for a few months for fear of fresh attacks by the Khmer Rouge.

Although my family and I narrowly managed to survive, many of my fellow villagers were not as lucky. The Khmer Rouge’s artillery shelling in Battambang was another tragedy of the Cambodian civil war, drawing international attention. According to a journal article by Ben Kiernan, a Professor of International and Area Studies and Director of Genocide Studies Program at Yale University, the artillery bombardment “killed at least 16 civilians and wounded dozens of others”. A few days later, the Khmer Rouge-run mobile radio station claimed: “Battambang town was set ablaze nearly the whole night”.

During wartime, Battambang was a critical theatre of military operations and such an explosion was common in everyday life. By then, we assumed that nothing had happened – it was a fatal assumption

By the end of September 1989 when Vietnam announced the final troop withdrawal from Cambodia. As the last Vietnamese military convoy was preparing to leave, the CGDK, particularly the Khmer Rouge forces, intensified their military offensives against the SOC and quickly captured a number of strategic towns.

The departure of the Vietnamese troops generated a huge power vacuum in Cambodia. A series of large-scale military offensives by the CGDK quickly turned the security situation into uncertainty and danger for the SOC. The artillery shelling in Battambang clearly indicated that even a ceasefire agreement remained out of sight, let alone a peace agreement.

Fortunately, the concerns that the SOC’s military would be unable to hold the line without the Vietnamese troops proved unfounded. The SOC’s military quickly re-grouped and launched counter-attacks to re-capture almost all of the lost towns from the CGDK. Failing to gain territory by forces could have been one of the important factors pushing the CGDK to return back to the long-standing peace negotiation that had been on and off since the mid-1980s.

Only eight months after my village had been bombarded, the Paris Peace Agreements were signed on October 23, 1991.

The Paris Peace Agreements have liberated millions of Cambodians from poverty and tragedies of armed conflicts. Cambodia managed to maintain a two-decade economic growth rate averaging 8% from 1998-2018. By 2015, Cambodia’s GDP per capita increased to $1,162 from $254 in 1993, helping Cambodia become a low-middle income country. Like any other part of Cambodia, my hometown of Battambang’s development is clearly visible through rapid urbanisation, physical infrastructure development, and better living conditions, including education and healthcare.

Cambodia’s transition to peace and development, however, remains far from complete. The definition of peace in Cambodia has long been a controversial topic given the mounting challenges, such development gap, social justice, media freedom, decline in democracy and human rights abuses. With the steep decline in civil and political rights over the last few years, Freedom House ranked Cambodia as “not free” in its annual Freedom in the World 2020 report. Equally important, Cambodia ranked 144 out of 180 in the most recent World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders.

To the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), peace should not be narrowly defined by the absence of war like I experienced, while development should not be narrowly defined by the GDP growth rate. Sustainable peace and development must be ensured by equality, equity, social justice, freedom, democracy and human rights.

After the Khmer Rouge’s artillery bombardment on my village that evening, few people believed that all the four conflicting parties in Cambodia would sign the Paris Peace Agreements only eight months later. But it did happen.

Unfortunately, the situation of democracy, human rights and media freedom in Cambodia has steeply declined since the dissolution of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) in November 2017. Several former CNRP members have been arrested and jailed for expressing critical opinions against the government on social media. The CNRP leader Kem Sokha, for instance, has been charged with treason and collusion with foreigners to overthrow the government. The court, however, has found no evidence against Kem Sokha yet. It is pretty clear that the legal actions against the opposition party are politically motivated.

By the end of 2020, according to Human Rights Watch, at least 60 civil society activists, human rights defenders, journalists, and ordinary citizens have been arrested for expressing critical opinions online and offline against the government. The ongoing deterioration of democracy and human rights have signalled not only deeper and more extensive political polarisation in Cambodian society, but also continued tarnishing the image of the Cambodian government in the international community.

To the opposition CNRP, to bring a political miracle to reality is to look forward to the future rather than looking back at the past. It could be very painful, but the opposition party needs to accept that the return of the dissolved CNRP party is highly unlikely. Restoring the status of the CNRP’s 55 MPs and commune councils is a mission impossible. Demanding such kind of political concession from the ruling CPP is a fait accompli. More importantly, staying abroad and relying on the international community to put more pressure on the ruling party is not a strategy of choice either. A political miracle cannot happen if such absolute terms and conditions are still on the negotiation table. The opposition needs to revise its political strategies to look for possibilities to negotiate with the ruling party to bring Cambodia out of the crisis.

All of these are not far beyond reach if all sides of the Cambodian politicians put aside their political differences and work on common interests for Cambodia and her people.

30 years ago, as a young primary school student, I witnessed the Cambodian political miracle. After the Khmer Rouge’s artillery bombardment on my village that evening, few people believed that all the four conflicting parties in Cambodia would sign the Paris Peace Agreements only eight months later. But it did happen.

To move forward to development and prosperity, Cambodia desperately needs national reconciliation and a sincere political resettlement. If Cambodian politicians made it happen in the past, there’s no reason they cannot make it happen again.

Sek Sophal holds a Master degree in Asia Pacific Studies from Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in Japan. He is a researcher at the Center for Democracy Promotion, Ritsumeikan Center for Asia Pacific Studies, as well as a contributing writer for Southeast Asia Globe.