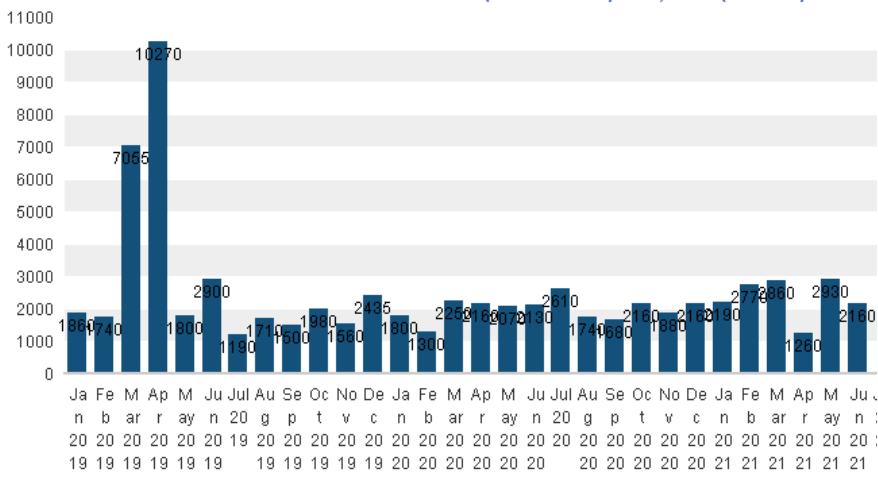

The months-long power cuts of 2019 caused hardship across Cambodia for residents and industry alike. Prices for the diesel needed to fuel backup generators rose daily; increasingly more expensive household generators were hard to find and factories and households both struggled to meet energy needs; production was reduced, daily life was impacted and everyone complained of the heat.

When the country’s hydro dam reservoirs ran dry and a very short rainy season followed, Cambodia’s dependence on this seasonal technology highlighted the risks of relying on rainfall to power a country with growing energy needs. The government had recently taken the much-lauded step of mothballing any mainstream Mekong hydroelectric projects. Heralded as an environmental step to protect vital Mekong ecosystems, the clear failure of hydro power to meet energy needs played an equally big role.

As energy bills grew and grid power didn’t return, frantic steps were taken; a Turkish power-generation ship was announced to be en route and then later cancelled, followed by the approval of a raft of coal and heavy oil powered plants.

lost among the rapid push to provide reliable and affordable electricity is a clear understanding of the reality of prioritising fossil fuels over renewable sources

How could Cambodia meet the growing demand for energy, while at the same time responding to environmental concerns about hydroelectric dams? In the absence of any clear plans for other renewable energies, coal was held up as the answer. In the eyes of government officials, coal is reliable, cheaper than importing grid power from neighbouring Vietnam or Thailand and a tried and tested technology that the national grid could handle without modification. Likewise, they feel the planned Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) development by 2025 would only further assist Cambodia in its energy independence from neighbouring imports; no matter that the coal and gas need to be imported and subject to price fluctuations and availability.

Yet lost among the rapid push to provide reliable and affordable electricity is a clear understanding of the reality of prioritising fossil fuels over renewable sources. Not just in terms of local impacts on environment and human health from burning such fuels to produce electricity, but from the perspective of brands and industries looking to decarbonise their supply chains. Namely those with RE100 or Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) commitments to run their operations using 100% renewable electricity. H&M Group has signed up to both.

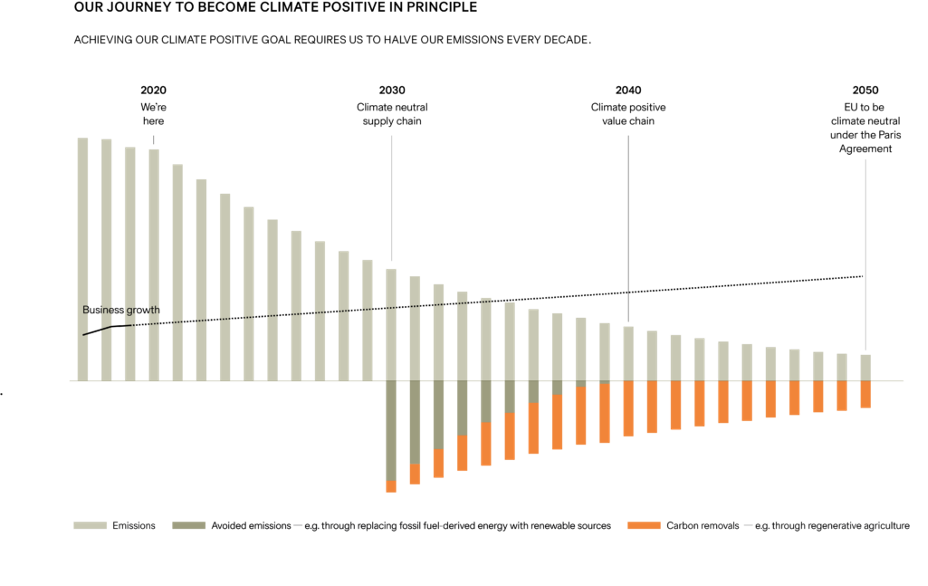

H&M Group has committed to become climate neutral across its supply chain by 2030 and climate positive by 2040. That means decisions on sourcing materials and manufacturing products takes into account the GHG emissions used to create them; all focus over the next 20 years is how to reduce these emissions.

Many countries globally are making strong commitments to increase the percentage of renewable sources of energy for their national grids. Bangladesh is working on a net-zero roadmap, Myanmar aims for more than 50% of electricity from solar and wind by 2030, even coal-exporting Indonesia has committed to no new coal power plants by 2023.

Many countries globally are making strong commitments to increase the percentage of renewable sources of energy for their national grids…Cambodia is going the opposite direction

Yet Cambodia is going the opposite direction. From a grid that is about 50% renewable today, its current Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the UN’s Paris Commitments plans point at only 25% of grid electricity coming from renewable resources by 2030. This is in part influenced by two recently completed heavy oil power plants, four coal power plants currently under construction, an agreement to buy coal power from Laos, and planned LNG developments in the second half of the decade.

This is concerning for brands seeking to reduce the environmental impact of production. The amount of carbon dioxide released by grid-connected power stations impacts data on ‘GHG-emitted per product’ for industries including garments, bags and footwear.

A grid that is ‘browning’ – adding more fossil fuel – directly impacts the energy data for factories. The amount of GHG emitted to produce one item will increase, thus negatively impacting that factory’s efficiency data. This forces extra spending by the factory on improving energy efficiency it would otherwise not need to do, including new machinery, more efficient usage of existing technology and rooftop solar. A ‘browning grid’ means the baseline is constantly moving in the wrong direction with factories constantly improving just to see small impacts.

Compare this to competitors in countries with ‘greening grids’ – an increasing percentage of renewables – whose investments in energy efficiency will complement the grid, further saving money and improving their ‘GHG emission per product’ data, which are both attractive for brands seeking affordable climate neutrality.

Vietnam’s adoption of rooftop solar has been remarkable, and this year the country is due to start its long-awaited USAID-funded ‘DPPA’ pilot, a virtual power purchase agreement plan that will allow industry to meet renewable energy requirements at no extra cost.

Bangladesh cancelled most of its planned fossil fuel projects and its High Court has demanded a roadmap for the country to have 100% renewable electricity. Even Indonesia, a major coal consumer and exporter, announced it will be home to the world’s largest floating solar project while seeking alternatives to coal within this decade.

While Cambodia’s four coal stations under construction cannot be stopped at this stage, the plans to buy coal power from Laos and the planned LNG projects should both be reevaluated. While Russia and the US are pushing LNG expansion to balance trade deficits, this fuel should stay in the ground and not cause further negative impact on future power generation for countries like Cambodia.

Cambodia still has time to improve the structure of its power development. In 2020 and 2021, the country saw its normal 20% annual growth in energy demand flatline and felt the pandemic’s hard impact on construction and industrial development, but also the closure of many of the power-hungry casinos in Sihanoukville. With energy demand for the future aiming to decrease through the efforts of projects supported by the EU and UNIDO, growth in consumption will slow.

Technological advancements in renewable energies offer increasingly feasible ways for energy needs to be met in ways that meet environmental needs. There are various good examples and innovative solutions.

Kampot and Mondolkiri provinces have demonstrated their suitability by providing wind power into the grid, while the national grid already has the capacity to support far more solar. The installation of solar panels on reservoirs behind hydroelectric dams, or ‘floating solar,’ allows water to be pumped upwards into reservoirs during the day and flow back to generate power at night, effectively turning hydroelectric infrastructure into giant, solar-supported batteries.

Additionally, with affordable battery storage on the horizon, factories with rooftop solar systems could meet almost all their electricity needs with Sunday recharging. Power Purchase Agreements connecting wind, solar or sustainable biomass projects to the grid, as well as certified Renewable Energy Certificates, would also support industries and attract further investments.

These options exist in varying degrees in countries that Cambodia competes against as an exporting nation. To meet the country’s energy needs, ensure environmental protection and spark business growth, the relevant ministries should prioritize these opportunities. The risk of inaction by Cambodia is far too high.

Peter Ford is a Programme Specialist Environmental at retailer H&M