In late September, protestors in Central Java, on Indonesia’s most populous island, stood outside a regional government office and vented their frustration at what they saw as inaction over complaints that the towering smokestacks of a nearby coal-fuelled power plant had been sputtering ash onto their farms.

With “we need clean air” and “we are covered in coal dust,” among the jeremiads, the protests echoed another long-standing struggle – near Batang, also on Java. There, locals have fought for years against the imminent opening of a 2,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant, part of the government’s plans to expand the electricity grid by 35,000 megawatts to meet the energy demands of an economy growing at 5% a year.

Such protests are likely to become more common across the region in the coming years, as urbanisation, industrialisation and increasing consumer spending in Southeast Asia’s growing economies spur a surge in energy demand. This in turn will likely prompt a trend-defying expansion of coal-fired power plants over the coming years even as most other regions lower their dependence on coal over environmental concerns.

“Coal is relatively more abundant and a cheap source of energy for the region,” said Siwage Dharma Negara, an economist at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, a think tank based on the grounds of Singapore’s National University. “Coal has been used extensively for so long and in fact, many power-plants in the region are built for coal-fired power-plants, hence they are the dominant source of electricity generation.”

Energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie projects a three-fold increase in electricity demand in the region’s biggest and third-biggest countries by population, Indonesia and Vietnam, which will account for much of the expected growth in coal burning.

“Coal will continue to be the dominant fuel source in power generation, peaking at 2027 before slowing down and accounting for 36% of the region’s power generation mix in 2040,” the group said in a September 25 report.

Since the near meltdown caused by the 1997-98 financial crisis, Southeast Asia as a whole has seen its economy expand five-fold, with average incomes doubling in many countries, goods trade tripling and investment also five times what it was at the turn of the millennium, to the point that Southeast Asia combined now sucks in more foreign investment than China.

Despite concerns about a seemingly intractable trade and technology stand-off between China and the US, the world’s two biggest economies, most of Southeast Asia looks set for a continuation of the two decades of high-speed economic growth that has lifted tens of millions of people across the region out of poverty and into what has long been known in the West as the consumer class.

“Declines in coal demand in Europe and North America will be offset by strong growth in India and Southeast Asia”

International Energy Agency

Launching the Asian Development Bank’s latest set of economic predictions in late September, which forecast gross domestic product growth for Cambodia of 7% this year and 6.8% in 2020, Sunniya Durrani-Jamal, the bank’s country director, described an economy that “continues to expand at a robust pace due to continued strength in traditional sectors such as garments, tourism, trade, and construction.”

The ADB, a Manila-based lender, predicts Southeast Asia as a whole will grow 4.5% this year and 4.7% in 2020, while bank HSBC contended last week that “amid all the global turbulence, ASEAN [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, a ten-country regional organisation] continues to impress with its resilience.”

“Indonesia’s growth should hold at 5%, helped by some extra fiscal spending, while in the Philippines rebounding infrastructure outlays should push growth again above 6% in 2020,” HSBC predicted.

Such expansion will fuel the already-growing energy needs across a once largely agricultural region. “[A]ll of the growth in energy demand comes from fast-growing developing economies, driven by increasing prosperity. China, India and other emerging Asia account for around two-thirds of the growth in energy consumption” predicted oil giant BP in its latest long-term forecast for energy demand up to 2040, which said that in most of Asia coal use will increase in tandem with overall energy demand.

The International Energy Agency, a Paris-based intergovernmental organisation, predicts that declines in coal demand in Europe and North America will be “offset by strong growth in India and Southeast Asia,” meaning overall global coal demand will stay much the same for the next five years. Total coal imports to Southeast Asia are expected to reach 127 million tons in 2019, a 27% jump from last year, with demand driven by existing and upcoming coal-fired power plants, according to S&P Global Platts, a commodities information business.

Coal is set to grow as a Southeast Asian power source, not just in bigger countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines, but in smaller peers such as Cambodia, which is putting up new coal stations to meet a growing demand for electricity and to offset the blackouts that still occasionally hit capital Phnom Penh.

Royal Group, a Cambodian conglomerate, is looking into building a 700-megawatt plant in Preah Sihanouk, a province in the country’s southwest. The project was expanded from an earlier 450-megawatt blueprint and could cost around US$1.3 billion if and when it goes ahead, with a 2023 start tentatively pencilled in by the Cambodian government. The province already hosts several coal-fired plants. A local subsidiary of Leader Universal Holdings from Malaysia runs two small 50-megawatt plants and is lining up another, while three 135-megawatt plants in Preah Sihanouk have been built by CIIDG Erdos Hongjun Electric Power, a Chinese investor.

At the turn of the century less than 20% of Cambodians had electricity, but after nearly two decades of 6-7% economic growth most years, that percentage has more than quadrupled to the point that almost 90% of the country’s 16 million people are hooked up to the power grid.

“Investment in renewables in Asia excluding China will overtake spending on upstream oil and gas projects in the region as soon as next year”

Rystad Energy

As goes Cambodia, so goes the rest of the region, across which there remains chunks of populations still denied a regular power supply. Country data available on the World Bank website show parallels between the 10% of Cambodians who remain without power and counterparts elsewhere.

Around 4 million Indonesians and 7% of the Philippines’ 106 million people remain disconnected from their national grids, while the relevant population percentages for Myanmar and East Timor, two economies that are sources of oil and gas, are 20 and 30 respectively.

6% of people in neighbouring Laos are awaiting connection to the country’s grid, despite the proliferation of energy-for-export dams built on Laos’ stretch of the Mekong river in recent years, an expansion that has earned the landlocked country the “battery of Asia” moniker.

As governments work to connect the rest of their populations, the question arises of how to generate the power needed to make up the deficit. BP contends that the “mix of fuels used in power generation is set to shift materially, with renewable energy continuing to gain in importance,” jumping from around a 7% worldwide share of total power generation to around a quarter by 2040.

Wood Mackenzie predicts that demand for liquefied natural gas from the South and Southeast Asia will grow over five times by 2040, with almost half of that growth emanating from demand in Indonesia and India, while investment in renewables in Asia, excluding China, will overtake spending on upstream oil and gas projects in the region as soon as next year, according to Rystad Energy, a research company in Norway, one of the world’s wealthiest oil economies.

“These countries each have strong pipelines for renewable energy developments of all types, including offshore wind,” said Gero Farruggio, Rystad’s head of renewables. “And, importantly, most have large targets outlining the inclusion of renewable power sources within their respective energy mixes, with corresponding support policies.”

Hydropower growth in mainland Southeast Asia has been dogged by concerns that dams on the Mekong are causing water shortages and environmental damage, meaning that the focus has turned to renewables such as wind and solar. The Philippines gets 15% of its electricity from renewables, a level that far exceeds the rest of the region, where the share, excluding hydropower, ranges from a negligible 0.1% in Vietnam and 0.9% in Cambodia to 5.9% in Thailand – all well below the average of around 10% for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a grouping of wealthy economies.

Indonesia’s 4.8% share is in part down to the same misfortunes of geography that leave it vulnerable to deadly earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanoes – an archipelago sitting along “a convergent tectonic plate boundary [that] makes it ideally suited for geothermal power production” – according to Fitch Solutions.

However, renewable power, such as that to be sourced from a new 60-megawatt solar plant in Cambodia, contributes much less to Southeast Asia grids than coal, which is relatively cheaply available from major exporters such as Australia and Indonesia.

“Governments often choose faster and cheaper way to increase the electrification ratio, by building coal-fired power plants,” said economist Negara. “So far, there is also lack of political commitment to develop renewable energy, mainly due to its high economic costs.”

Coal, some of it imported from Indonesia, accounts for 48% of Cambodia’s power supply, a percentage that is likely to increase in the coming years as the planned power plants come on stream, though the 60-megawatt solar plant in Kampong Speu province is due to go live by the end of this year and another 100-megawatt solar facility is being lined up for Kampong Chhnang. Again, it is a similar story across Southeast Asia, where coal accounts for anything from 1.2% of electricity in tiny Singapore to well over 40% in Malaysia and the Philippines.

That number jumps to 56% in the region’s giant, Indonesia, a major coal producer – which is in the midst of a huge expansion of a power grid still prone to occasional outages, including a recent weekend breakdown affecting tens of millions of people in the capital Jakarta and surrounding areas of densely populated West Java.

As coal has declined in importance in Europe and North American, most countries in Southeast Asia have seen coal become increasingly central to power generation since the turn of the century. In 2000, only 36% of Indonesia’s electricity was coal-generated, while coal use in Cambodia, Malaysia and Vietnam has more than doubled since then, an expansion that former World Bank President Jim Yong Kim slammed as a “disaster for the planet” in 2016.

The 2015 average coal-for-power-generation dependence in the OECD was 29.6%, the same as Vietnam, but unlike most of Southeast Asia, coal use in the OECD is on the way down, having dropped nearly 10 percentage points since 2000.

Southeast Asia’s coal habit is worsening as even China – which will nonetheless remain the world’s biggest coal user – increasingly looks to renewable sources or to gas-powered plants.

“While China accounts for nearly half of the world’s coal consumption, its clean-air measures are set to constrain Chinese coal demand going forward,” predicts the IEA.

Southeast Asia’s huge infrastructure needs, including in power plants, offer lucrative investment opportunities for cash-rich neighbours with the know-how to build. For governments in the region, it is a question of who is willing to fund the work, as most administrations concede that the vast infrastructure spending needs they face cannot be covered solely by domestic revenues.

China and Japan, Asia’s two biggest economies by far, have stepped in. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry describes coal as “an energy resource that has the advantage of stable, lower prices than other fossil fuels due to abundant resources and relatively wide distribution” but concedes that the fossil fuel has “the disadvantage of imparting a larger environmental load when combusted due to its higher carbon, sulfur, and ash contents.”

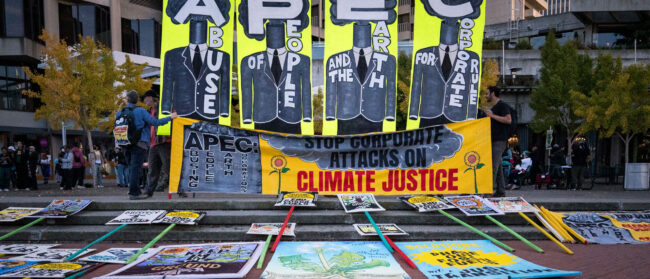

Japanese investment in coal plants across Southeast Asia has sparked protests by environmentalists, however, including during Tokyo’s recent hosting of a summit of the Group of 20, mirroring the concerns over Japan’s domestic revival of coal power plants in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Chinese investors have been particularly prominent in building new coal-fired plants in Vietnam over the past half-decade, a trend that is likely to continue, as its financial institutions are the world’s biggest source of funding for overseas coal plants. The Natural Resources Defense Council, a US-based environmental research group, estimates that China has US$15 billion sunk into foreign coal projects since 2013 – the year Beijing announced its Belt and Road Initiative, a mammoth intercontinental infrastructure blueprint.

“Access to coal financing from China, Japan and South Korea remains forthcoming given that these markets will continue to stimulate external demand for domestic coal power equipment in Asia, supporting coal-fired power growth,” said Daine Loh, power and renewables analyst at Fitch Solutions.

So even as overall coal use in China declines, the much-maligned black stuff will remain, according to BP, “the dominant source of energy for power generation in the rest of Asia, accounting for the vast majority of the increase in power generation in the region.”

Jacqueline Tao, a research associate at Wood Mackenzie, said that Southeast Asia still had some way to go to wean itself off coal.

“The reality of rising power demand and affordability issues in the region mean that we will only start to see coal’s declining power post 2030,” she said.