Matthew Friedman is building an army.

During a career of decades including work for US and United Nations development agencies, Friedman has fought a relentless campaign against human trafficking and slavery throughout Asia.

Now the advocate, author and founder of the Mekong Club, an anti-trafficking business organisation, works to recruit troops and expand what he calls a “second-generation abolitionist movement.”

In his 2021 book, “Where Were You? A Profile of Modern Slavery,” Friedman calls on ordinary people to accept responsibility and play a role in ending the commercial and social conditions enabling trafficking and exploitative labour.

“We need a series of tools to make a compelling case for their involvement,” Friedman said. These include speeches, books and articles informing and inspiring people to lend any support they can offer, whether time, money or communication.

“This approach will create a vast army of committed volunteers who will form a community of initiators, facilitators, motivators and responders,” he said in an email from his home base in Hong Kong, where he lives with his wife and fellow modern slavery activist, Sylvia Yu Friedman.

The book’s foreword by Kathleen Ferrier, a former member of parliament in the Netherlands, states there are more than 40 million “modern slaves,” including those held against their will in brothels and pressed into unpaid or marginally compensated jobs in the garment, construction and entertainment industries. They may be victims of crime, voluntary migrants or refugees who fall prey to traffickers and crooked employers.

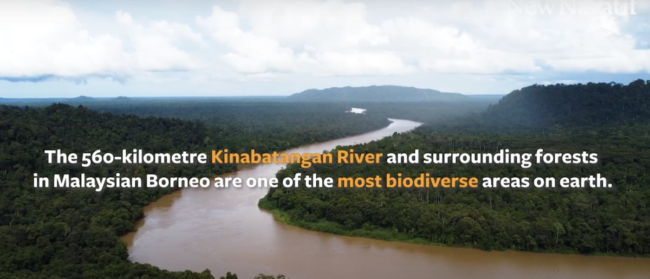

The fishing industry is particularly notorious. Describing working conditions for Southeast Asian migrants on Chinese vessels, Rebekah Baynard-Smith wrote in 2020, “The ‘symptoms’ characterising forced labour in this industry often include workers being assaulted, overworked, underfed, forced to drink filtered seawater, withheld payments and denied access to their personal documentation.”

Friedman contends global consumerism is an essential driver of illegal bondage.

“With so many human trafficking victims associated with supply chains, we have all purchased goods that are directly or indirectly connected with modern slavery. We must not ignore this reality,” Friedman said. “The more desire we have for cheap products, the more potential for factories, fisheries and farms to exploit workers to meet this demand.”

Friedman recognised the importance of business as a cause and potential remedy for exploitation when he founded the Mekong Club in 2012. The organisation helps companies understand the problem’s extent and adverse effects through executive training programs and focused technical assistance for legal and compliance officers. The club’s ultimate goal is to “offer the right tools needed for companies to reduce risks of slavery affecting their business in any way,” he said.

“I firmly believe that the private sector has the power to significantly reduce the number of cases of human slavery through more detailed supply chain audits and more direct involvement of their leaders,” Friedman said.

In addition to a business concern, Friedman said human trafficking is a public health issue, with evidence of increased injuries, suicides, addictions and sexually transmitted and communicable diseases. To those who profit from human misery, illness and suffering are part of the cost of doing business.

The risk of modern slavery has skyrocketed globally as the dire economic impact of this pandemic has increased”

Matthew Friedman

“If more money can be made if a prostitute is told not to wear a condom, most traffickers will not care. There are many documented cases of boat captains throwing sick or injured workers off the boat rather than taking them in for treatment,” he said. “Trafficking victims are often considered disposable commodities. If money is required to protect their health and well-being, this is often ignored.”

The global struggle with Covid-19 has exacerbated conditions that force people into poverty and ripen opportunities for exploitation. Quarantines have slowed or damaged many businesses with factory shutdowns, order cancellations, workforce reductions and sudden supply chain restructuring, he explained.

“The risk of modern slavery has skyrocketed globally as the dire economic impact of this pandemic has increased,” Friedman said, citing the example of Asian garment workers employed by international fashion brands that suffered huge losses in the early months of the health crisis. “Many unemployed workers were forced to turn to exploitative jobs, and some even made their children take work in order to survive.”

In desperate economic periods, some workers find the only solution, beyond toiling for food rather than wages, is to take loans from employers who then exploit their indebted personnel. Migrant workers, who also incur bills during recruitment or travel for ostensibly gainful employment abroad, are especially vulnerable to this “debt bondage,” Friedman said.

Debts to money lenders, community institutions or family members also may increase opportunities for exploitation, he said.

“Human traffickers prey on those who are economically vulnerable. Without a paycheck and generally unable to rely on personal savings, the possibility that an unemployed worker will find themselves bearing excessive debt significantly increases,” he said.

Friedman’s title, “Where Were You?”, comes from a 15-year-old girl who was tricked into marriage in Nepal and forced into prostitution in India, suffering vicious beatings, disease and humiliation among numerous other horrors inherent to sexual slavery. Friedman was researching a book and talking to survivors of sexual slavery when Gita, whom he said was “systematically raped over 7,000 times over a two-year period,” turned the focus onto him.

She was angry at Friedman and others who failed to take action to save the victims who remained under the control of traffickers, she said.

“Where were you when I was in that terrible brothel? I sat there every day waiting for someone to come and save me,” she said. “I knew that everything happening around me was illegal and wrong. Where were you and everyone else when I needed you?”

Friedman compared the question’s moral quandary to those who were absent while millions died in the Holocaust. He acknowledged that in the past, and again now, a lack of public awareness rather than an absence of compassion is usually the root of inaction and the reason he spends each day rallying more volunteers to his anti-slavery corps.

Friedman wrote “Where Were You?” to encapsulate the knowledge and lessons he has garnered from work in more than 40 countries, including overseeing projects in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

“The goal was to help the reader really get a sense of what is the issue, how does it work, how does it affect the victims, who are the perpetrators, what is being done to address it and to do it in one manuscript so the reader has everything they need in one place,” he said.

Friedman calculates that less than 10% of the people he meets at speaking engagements are aware of the full extent of modern slavery, which he attributed to inadequate communication in a society where a single topic can easily drown in the information flood across the internet and social media networks.

“Let’s face it: few people have a basic awareness of the major issues of our time,” he said, adding that people cannot feel compassion for a problem they don’t know well. “And if you don’t care, you will do nothing about it.”

Another obstacle is the reckoning with the idea of millions of labourers losing their liberty and suffering extraordinary abuse every day. People “shut their minds to the topic because it is too depressing,” Friedman said.

He recounted a presentation in Canada, after which a woman told him she regretted attending because his talk “ruined my day. I don’t want to feel this way.” Faced with upsetting information, Friedman said “many people will simply ignore the topic altogether.”

He is frequently approached by others who profess a sincere desire to help, but the passion usually doesn’t last after the speaker and his subject slip from their sight.

“Even after handing them my business card and agreeing to work with them, I seldom get more than one or two who follow through. Sometimes none of them do,” Friedman said. “The momentary intention might be there but the commitment to follow through is sorely lacking.”

While many people might not see, or want to see, the world of modern slavery, he said the most effective strategy against the exploitation economy is through a contemporary abolitionist movement, like the organised, public effort to end slavery in the US and UK in the 1800s.

“We can step up and volunteer within one of the many anti-trafficking groups. We can raise money for the cause or donate our own funding to help. We can support government efforts to help fight the problem. The idea is to use our own talents to fight slavery,” Friedman said, encouraging art projects, films and writing to support the movement. “Whatever you do, do it in the direction of freedom. The same can be said if you are a teacher, social worker, doctor, lawyer or anyone else. If 10 million people did one act each that is 10 million acts.”

Human trafficking and slavery in dark and distant corners affect “life on Main Street,” he said, noting that free people who enjoy human dignity must take responsibility to secure those rights for others, even if only through small maneuvers to aid the larger struggle.

“I have come to realise that if those of us who work on the modern slavery issue could solve it, we would. But the fundamental truth is that we simply can’t,” Friedman said. “This problem goes well beyond what a few thousand people around the world can fix. This issue requires an army of united people – people who care.”