According to reports last week by international media, the ASEAN bloc has finally chosen Brunei’s Erywan Yusof to fill the long-awaited position of special envoy for Myanmar, following more than three months of division over the choice among member states.

However, the nomination of Yusof, the sultanate’s second minister for foreign affairs, is unlikely to produce any significant diplomatic resolution to the protracted crisis in Myanmar as a result of the February 1 military coup. If there is any hope for genuine restoration of Myanmar’s democracy, individual ASEAN countries that desire such an end goal must be prepared to act alone.

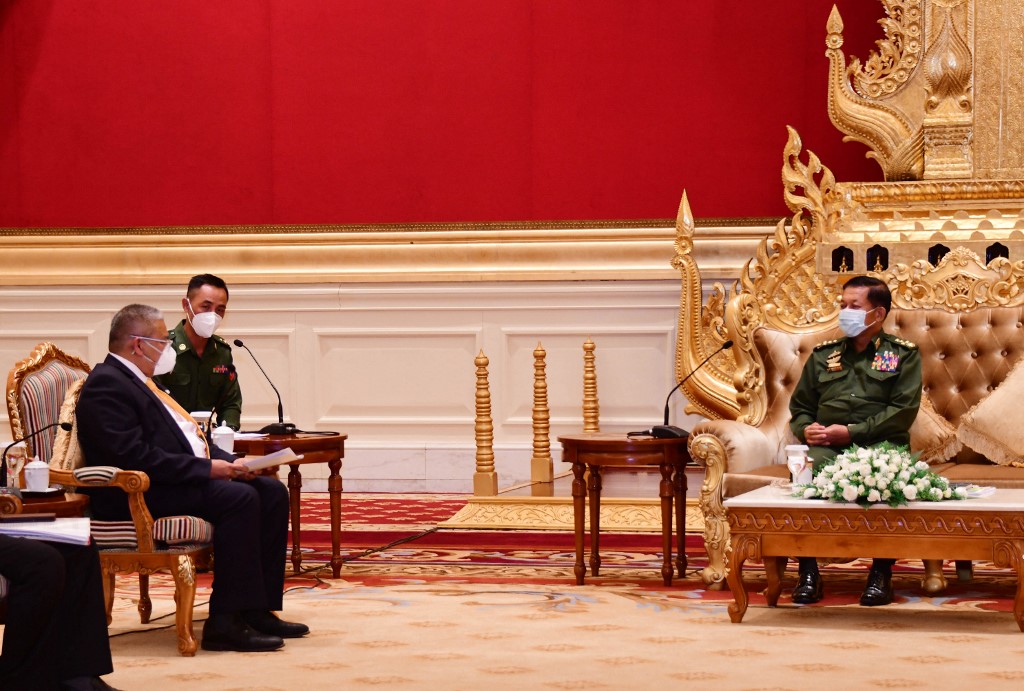

While the designation of a special envoy is a significant procedural achievement for the divided group, which includes ten countries and operates on a consensus basis, there are reasons to be skeptical. First and foremost, Erywan’s performance so far with regard to the crisis inspires little confidence in his future ability to challenge the Myanmar military’s grasp of power. The second minister traveled to Naypyidaw in June, along with the ASEAN Secretary General Lim Jock Hoi, in what some hoped would be the first step in establishing lines of communication between junta leaders and the ousted civilian government.

After all, ASEAN had agreed to a Five-Point Consensus following a special summit in April, which specifically called for the envoy “to meet with all parties concerned”. However, the Brunei delegation failed to get a meeting with ousted civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi or representatives from the National Unity Government established since the February coup. It is not even clear if they tried to arrange such a meeting.

Worse, the press release which the ASEAN Secretariat issued following the visit affirmed Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing and other junta leaders’ self-designated political titles as the political leaders of Myanmar, which some ASEAN members contest. All in all, the visit badly damaged Erywan’s credibility as a neutral liaison or capable diplomat and instead conferred the State Administrative Council (SAC), as the military junta calls itself, unwarranted legitimacy.

The Five-Point Consensus further called upon the special envoy to “facilitate mediation of the dialogue process”. But hope for that is dwindling since Erywan has not yet managed to establish contact with the elected leadership of Myanmar, whom the junta has imprisoned and labelled as a “terrorist organisation”.

Erywan seems to have emerged as the compromise candidate between two polarising alternatives: Thailand’s former deputy foreign minister Virasakdi Futrakul, whom the generals in Naypyidaw reportedly preferred, and former Indonesian foreign minister Hassan Wirajuda, who was expected to take a firmer line in standing up to the Myanmar junta. Veteran diplomat Razali Ismail, a former chairman of Malaysia’s Human Rights Commission and president of the UN General Assembly, was also rumoured to be in the running for the position.

After months of division over the position – largely pitting ASEAN’s more democratic states, including Indonesia and the Philippines, against their autocratic counterparts Thailand and Brunei – Erywan represents a tolerable middle ground for most parties. The Indonesians in particular seemed to have grown exasperated by the delays, with Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi pressing ASEAN to come to a swifter decision and calling out the lack of progress.

Min Aung Hlaing has made a farce of the ASEAN five-point consensus

If the selection was not milquetoast enough, ASEAN allows the Myanmar junta to approve the choice of special envoy. This leads into the second reason for tempered expectations, which is Min Aung Hlaing’s demonstrated ability to wield ASEAN summitry for political theatre.

The military will continue to engage the toothless bloc to serve its own ends of legitimising its own rule while shifting the goalposts further down the line in order to extend its grip on power. It will not compromise unless regime survival is at stake. So far, it has no serious reason to feel its hold on power is seriously threatened – at least not by any of its neighbours, with domestic armed groups likely posing a more serious threat.

Min Aung Hlaing has made a farce of the ASEAN five-point consensus. While he half-heartedly expressed rhetorical commitment to the document at the special summit in Jakarta in April, upon returning to Myanmar, he vowed that the regime would have to restore “stability” before implementing its steps. The regime has killed hundreds more innocent civilians since the summit, with a total death toll nearing 1,000 since the coup.

The commander in chief has repeatedly promised to hold elections but most recently extended a state of emergency for another two years. The general has also appointed himself prime minister of a new “caretaker government”, a phrase which has historical connotations in Myanmar, since it is the same term the military used in 1958 to take power from Burma’s first democratically elected Prime Minister U Nu.

The difference from that is that the military back then at least tried to establish a veneer of legitimacy for its coup by coercing Nu’s approval for the transfer of power to General Ne Win.

What to expect now? Next steps

The military will continue to carefully stage-manage the ASEAN envoy’s access to the country and it also has no qualms holding its people hostage in return for humanitarian assistance, which will inevitably flow through the military.

It’s conceivable that a different special envoy may have been able to broker a more rapid or pragmatic solution on this front. After all, Hassan Wirajuda, one of the individuals considered for the role, was instrumental in facilitating access for humanitarian assistance to Myanmar in the wake of Cyclone Nargis in 2008 when the generals dragged their feet – a considerable diplomatic success.

Thus it is unsurprising the Indonesians are none too happy their preferred candidate was not selected for the position. Foreign Minister Marsudi has been particularly critical of ASEAN for making “no significant progress” on the envoy decision and on August 2 urged her counterparts to act decisively: “We must not be silent and allow the suffering of the Myanmar people to continue.”

The choice therefore exposes a rift among ASEAN members with more democratic states backing Indonesia’s choice and the Thais, who more successfully formed a military government following a 2014 coup, putting forward a more regime-friendly candidate. That fundamental gap allows Min Aung Hlaing to exploit ASEAN’s weaknesses.

It will come down to individual member states who have a clear interest in encouraging Myanmar to resume its democratic transition to apply pressure unilaterally

At any rate, whatever the special envoy is able to achieve, one thing is certain: ASEAN has no enforcement mechanism to pressure the Myanmar junta to relinquish power and restore the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi.

Therefore it will come down to individual member states who have a clear interest in encouraging Myanmar to resume its democratic transition to apply pressure unilaterally. It would help if they were more willing to support targeted economic sanctions against the military, but so far ASEAN states have shown no interest in doing so. Barring such measures of financial coercion, veteran diplomats must rely on the power of persuasion and old-fashioned diplomacy.

Are senior statespersons like Marsudi, Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan, or even Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad willing to step up in an effort to form a coalition to oppose the Myanmar junta and convince Min Aung Hlaing that he has gone too far? All three have vocally condemned the military’s violence at one time or another.

Just three weeks after the coup in late February there were signs that Marsudi might be capable of bringing both sides together for “intensive” talks after meeting junta-appointed foreign minister Wunna Maung Lwin and elected representatives of Myanmar’s Parliament, known as the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), in Bangkok.

In recent months, however, hope has faded as ASEAN squandered the momentum of April’s special summit. Barring a personal transformation on the part of Erywan Yusof, which would represent significant divergence both from Brunei’s own authoritarian system as well as its diminutive diplomatic role within ASEAN, responsibility for action now falls to individual member states.

Who will rise to the occasion as Myanmar’s military continues to wage a ruthless and costly war against its own people? As yet, the answer is unclear.

Hunter Marston is a PhD candidate in the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs and a nonresident WSD-Handa Fellow at Pacific Forum. He has published on Myanmar politics in the Asian Journal of Political Science, the Lowy Institute’s Interpreter, Frontier Myanmar, the Washington Post, and Foreign Policy, among other places.