I never thought I would be so happy to hear someone had tested positive for Covid-19. For most of us, infection is treated as a calamity, or at the very least a major inconvenience. For Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam, it was literally a lifesaver.

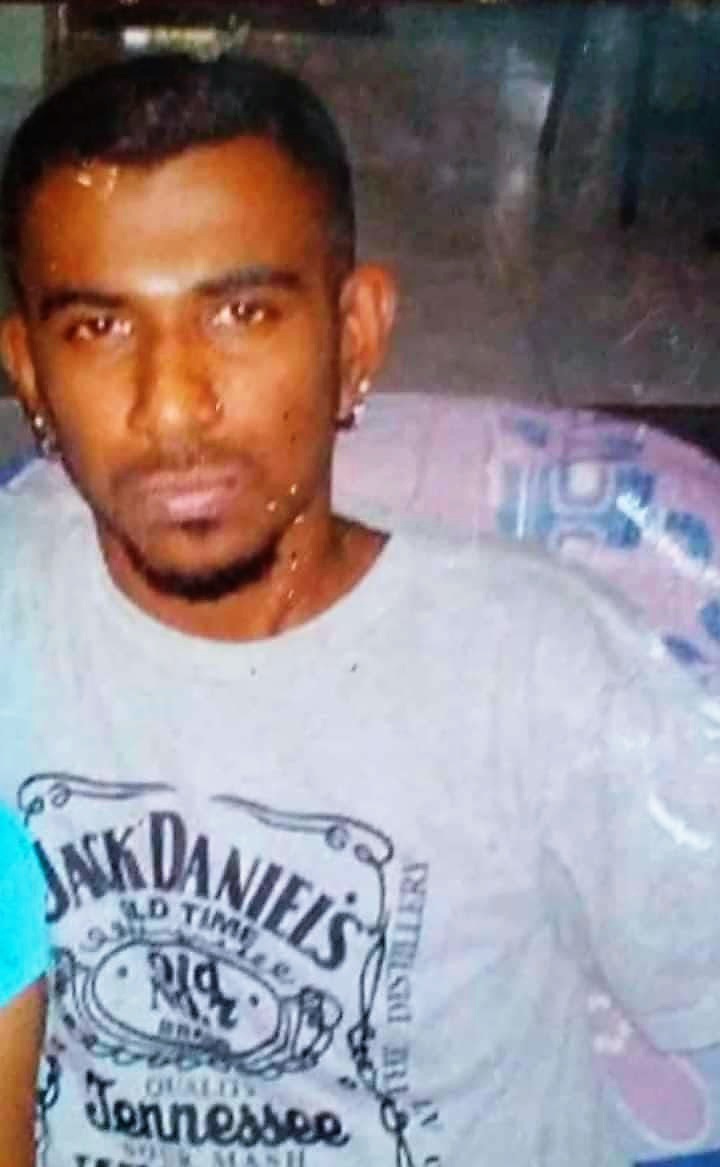

Nagaenthran, or Nagen to his family, was supposed to die in Singapore on the morning of 10 November. The prison authorities had already sent a notice of execution to his family in Malaysia two weeks prior, ruining their Deepavali celebrations as they scrambled to arrange travel to Singapore at a time before vaccinated travel lanes were opened between the countries.

A day before the scheduled execution, Nagen received a reprieve by testing positive for Covid-19. An appeals court adjourned his hearing and extended his stay of execution.

There is no process of ending a life as calculated and administrative as the death penalty. The absurdity of delaying the execution of a man until he recovers from Covid-19, waiting for him to become healthy enough to kill, is obvious to many people. But those of us who track and document the application of capital punishment are familiar with such nonsensical cruelty.

Additionally, the death penalty policies of many nations, including some in Southeast Asia, can pull family members into the punishment process through indeterminate execution dates and fluctuating sentences that cause further mental and emotional strain.

When he arrived in Singapore in November last year, Nagen’s younger brother, Navin, found him in a worrying state. It was the first time the brothers had seen each other in years, and Navin said that Nagen’s mental condition had deteriorated since their last meeting.

Navin told an anti-death penalty activist that his brother had difficultly making eye contact and claimed he took three-hour daily baths. Even before spending more than a decade in a single cell on death row, Nagen had an IQ of only 69 and cognitive impairments.

Navin wondered if his brother really understood he was going to be hanged.

These troubling details have not been enough for Singapore’s government cabinet to advise president Halimah Yacob, who has no discretion of her own, to commute Nagaenthran’s death sentence.

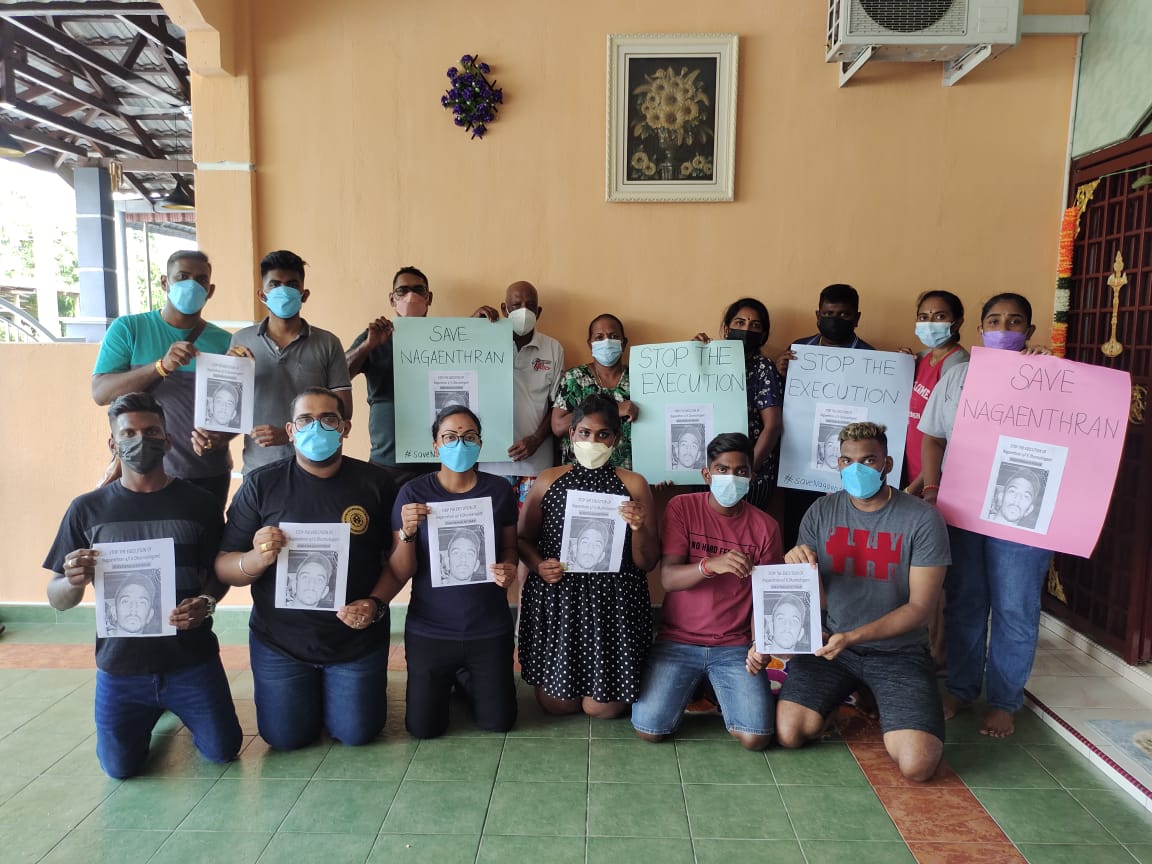

There has been no shortage of pleas for mercy on Nagen’s behalf. They have come from the Malaysian monarch, international human rights organisations, United Nations human rights experts, foreign embassies, public figures such as billionaire businessman Richard Branson and British actor and writer Stephen Fry and ordinary Singaporeans.

So far Nagen has been shown more mercy by the coronavirus than the Singaporean state.

When people hear the death penalty described as ‘cruel and inhuman punishment,’ they often think of its most gruesome aspects: nooses and firing squads or botched executions in countries like the US. The reality is that the cruelty begins far earlier and in more mundane forms.

They had been put through an emotional wringer, bounced between relief and despair

In Singapore, the question of whether a drug courier can escape the gallows could potentially come down to whether the prosecution thinks they’ve been useful enough to receive a ‘certificate of substantive assistance.’

In the case of Pannir Selvam Pranthaman, his cooperation in giving information to the authorities was considered insufficient for him to be spared the gallows because the police did not use his tips. Without clemency from the nation’s president, Pannir remains at risk of imminent execution.

In the past decade, I have witnessed the many ways in which capital punishment inflicts pain. Kho Jabing, a migrant worker from Sarawak, was sentenced to death in Singapore after a drunken robbery led to the victim’s death. I met his family in 2015. They had been put through an emotional wringer, bounced between relief and despair.

Due to legal amendments, Jabing was first sentenced to death, then re-sentenced to life imprisonment with caning and then sentenced to death again. After a desperate campaign supported by lawyers seeking further stays of execution, Jabing was eventually taken straight from a last-ditch court hearing in May 2016 back to prison and hanged.

The whole process took place so swiftly that his family’s last visit was conducted via video conferencing. It was his younger sister’s birthday. She recently told me that she still has trouble sleeping when she thinks of her brother or hears of an impending execution.

In 2020, the family of Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin, who was due to be hanged for drug offences, went through a day of anxiety and stress after being told by prison officers that there was no information about a stay of execution, despite his lawyer obtaining a stay order from the court that afternoon. The prison finally informed Syed’s sister later in the night that the execution would not go forward.

These administrative methods of pain delivery are not unique to Singapore. In every country applying the death penalty there are similar examples of circumstances compounding the harshest punishment.

Two prisoners on death row in Japan sued the state over the policy of issuing a notice of a hanging only hours before the sentence is carried out, keeping inmates in a constant state of fear. This is a mental torment not just for prisoners, but for loved ones who bear the trauma for years afterward, despite having committed no crime.

“They are punishing our entire family,” Nagaenthran’s older sister, Sarmila, told The Washington Post last year.

It is a feeling the loved ones of death row prisoners know all too well. Apart from Nagen, numerous death row prisoners have exhausted their legal appeals, leading to fears that a backlog in cases will lead to a large increase in executions.

Government and legal authorities might say these cases have been given due process in accordance with the law and justify the death penalty as necessary for safety and security.

Yet when countries establish entire bureaucracies dedicated to taking lives, we should all think about how this reflects on society and the harm we might be causing.

Kirsten Han is a freelance journalist, anti-death penalty activist and Transformative Justice Collective member who has worked with families of death row prisoners in Singapore for a decade.