Singapore is a country that believes in “tough love”.

Punishment is framed as justice, upheld for the good of the many. Deterrence is the goal. Often, when high-profile crimes of shocking malice or cruelty hit the front pages, the automatic reaction is to demand harsher penalties. A new group I’m involved with, the Transformative Justice Collective, or TJC, is seeking to change this.

The impetus for forming this collective in October last year came from Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin, a Singaporean man who had received the mandatory death penalty in 2016 after being convicted of having no less than 38.84g of heroin. Under Singaporean law, being found guilty of trafficking 15g or more of heroin is enough to get one sentenced to death. It’s all part of the country’s war on drugs.

Things were getting desperate for Syed at the time; he and his family had been informed that his execution date had been set. In a bid to drum up public support, the rapper and activist Subhas Nair and his friends set up a Change.org petition urging Singapore’s president to grant Syed clemency.

The petition went beyond just Syed’s case, pointing out that people grappling with addiction require support, that Malays are disproportionately affected by drug-related policing and sentencing, and calling for a rethink of Singapore’s approach to drug users and mules. It ended up garnering over 30,000 signatures.

As an activist who has been involved in the anti-death penalty campaign for the past decade, I was surprised by the response. Previously, when I wrote on social media about abolishing the death penalty and moving away from Singapore’s punitive methods of dealing with drug use, I’d get trolled and flamed by outraged Singaporeans, accusing me of wanting to let harmful substances flood into our tiny country.

Such an angry response is an echo of the government’s own rhetoric, which justifies this harshness as life-saving. They argue that, with capital punishment deterring drug trafficking, the law reduces the amount of drugs circulating in Singapore, thus reducing the chances of people abusing these substances.

Between 1991 to 2019, the state hanged 491 people, the majority of whom had been convicted of drug offences. The same logic applies to lesser drug offences that don’t attract the death penalty: of the entire penal population, drug offences form the largest category of inmates. Even efforts at rehabilitation are first and foremost rooted in punishment.

Addressing substance use disorders and the drug trade isn’t as simple as labelling anyone who has ever been involved with drugs a criminal

Those who have spent time in the state-run Drug Rehabilitation Centre – also operated by the Singapore Prison Service – say that it’s essentially prison, with a sprinkling of rehabilitation-esque sessions like workshops on addiction or reintegrating into society upon release.

These dominant narratives and knee-jerk reactions obscure a much more complex situation. With the relatively positive response to the petition to save Syed, it finally seemed to delve more deeply into the subject and push people to think more critically about crime and punishment.

Every drug user has their own story and experience: some consume drugs for pleasure, while others use drugs to stay awake and make it through high-stress or gruelling jobs with long hours. Some people are recreational users, while others develop substance use disorders that require treatment and care. People also have differentiated access to support; while some can afford to seek treatment via private (and more expensive) avenues, others don’t have this privilege.

Once we pay attention to these diverse experiences, we realise that addressing substance use disorders and the drug trade isn’t as simple as labelling anyone who has ever been involved with drugs a criminal. There are push and pull factors that lead people to use drugs or participate in the drug trade, and socio-economic circumstances that leave particular communities more vulnerable to not only drug use, but also surveillance and policing. The demographics of Singapore’s penal population are not reflective of our society – ethnic minorities are disproportionately over-represented.

We felt that it was a good time to finally start pushing these points – about drug policy, restorative practices, and the need to address systemic inequities – into the Singaporean consciousness. We also intentionally adopted a wider frame and scope: although the abolition of the death penalty is a priority, we also look at the wider criminal punishment regime, from prison conditions and prisoners’ rights, to the myths and problems associated with Singapore’s punitive approach.

The concept of transformative justice, a framework that seeks to respond to violence and harm without creating more damage, has been proposed and discussed in many contexts around the world, but is still fairly new to Singapore. While TJC’s members believe in harm reduction and the need to move away from increased policing and incarceration, we recognise that most Singaporeans don’t yet know enough about how criminal punishment works in our own country to engage in deeper conversations about the reforms that are needed.

This is why much of TJC’s current work has to do with interviewing formerly incarcerated people, documenting their experiences, organising events and discussions, and producing explainers on social media educating people on various aspects of crime, punishment, and how things work within the Singaporean system.

Instead of focusing on single issues, we also make a point to highlight intersectionality and systemic or institutionalised issues that feed into problems such as the abuse of exploited migrant workers, or offences committed by juveniles. While we’ve raised funds to pay an honorarium for a coordinator, most of the work is volunteer-driven.

It’s early days yet; we’re not even a year old. I know from past experience that the Singapore government doesn’t like anti-death penalty activists, characterising us as “romanticising” death row inmates, but the authorities have left TJC alone so far, seemingly comfortable to ignore our efforts.

It doesn’t bother us. For now, we prefer to direct our energies and attention towards public education and extending solidarity and support to incarcerated people and their families. We’re encouraged by the response we’ve received; people reach out to volunteer or donate to our work, and show up to our online events, participating enthusiastically in panel discussions and workshops. A critical reading group we recently launched on incarceration filled up so quickly we had to start writing apologetic messages to people disappointed to find themselves already stuck on the waiting list.

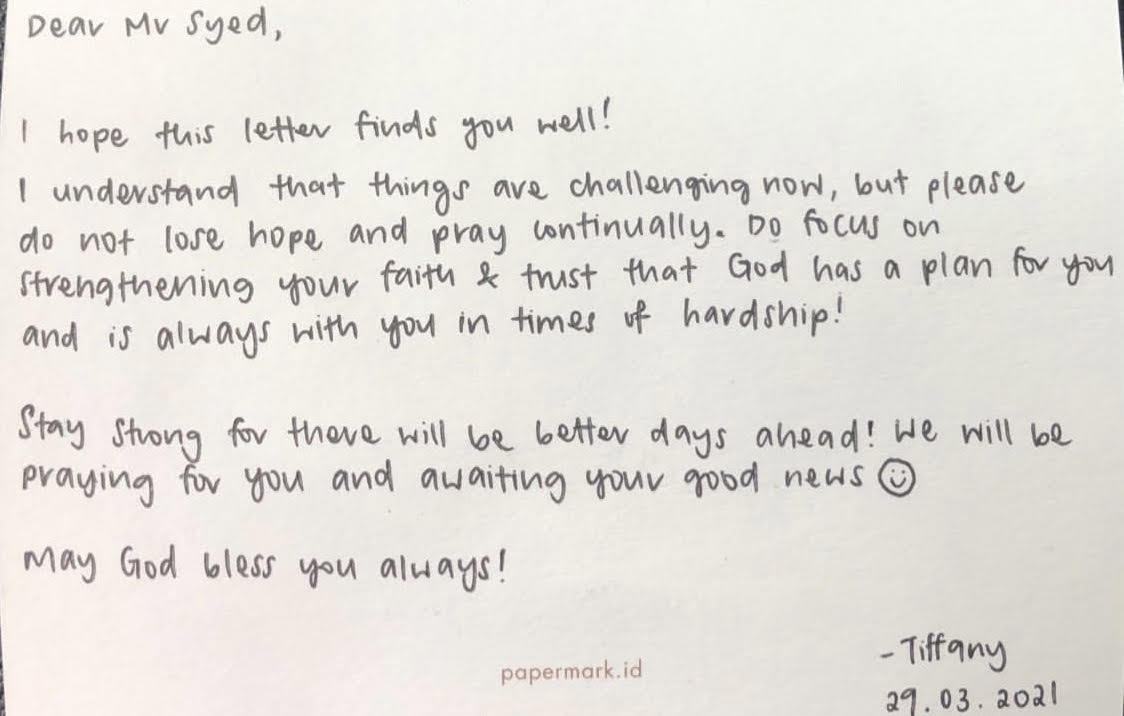

Thanks to the tireless efforts of M Ravi, a human rights lawyer, Syed was granted a stay of execution. He remains on death row in Singapore, but pending applications before the courts have bought him, and other death row inmates, more time.

For far too long, Singaporean discourse has conflated punishment and retribution with justice. We’ve developed a habit of assuming that things have been put right as long as perpetrators are put through the requisite suffering. Violence, harm, and substance use disorders are framed as manifestations of individual defects; we rarely take the time to ponder systemic inequities that provide the environment within which certain harms and abuse occur.

To begin imagining a different way forward, we need to ask ourselves what we actually mean when we talk about “justice”. It’s a challenge that the Transformative Justice Collective has set for ourselves, and our society.

Kirsten Han is a freelance journalist, activist, and member of the Transformative Justice Collective. She runs the newsletter We, The Citizens, covering Singapore from a rights-based perspective. You can donate to support the work of TJC here.