Malaysians take their food seriously. If there is one thing most Malaysians can agree on, it is their undying love for food – especially food served in the cornerstone of the nation’s pride in food culture, 24-hour mamak stalls.

In the dead of the night when most food stores have pulled down their shutters, Malaysia’s mamak stalls stay open to serve food loaded with carbohydrates to hungry night owls.

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck Malaysia, restaurants were forced to close at 8 pm to meet public health restrictions. The government-mandated curfews caused a downturn in sales for food businesses including mamak stalls, which typically received a large chunk of their business serving all walks of life long after sundown.

A sudden lack of manpower from foreign workers, early closing times and the general reduction in social gatherings resulted in the closure of at least 2,000 mamaks across the country.

But after two quiet years, Malaysia’s favourite late-night dining culture has received the green light to renew 24-hour operations, signalling the return of one of the nation’s favourite pastimes and a staple hangout for the country’s disparate cultural communities to come together.

A mamak is generally separated into multiple sections. The entrance is usually lined with ingredients for nasi kandar – trays of meat in curry, vegetables, rice and an assortment of fried foods. Closer to the back of a mamak are normally packs of chicken- and curry-flavoured instant noodles. Bread is made in another area while tins of condensed milk and sugar syrup are found in the drinks section.

Stainless steel chairs and tables fill the restaurants, some outfitted with flat screen televisions or projectors so patrons can catch the latest programmes or live football matches.

Mamak staff make rounds among customers and memorise complicated orders with ease: less sugar, less ice, no onions, more cheese. No two mamaks are the same, some even carry their own signature dishes and beverages.

But mamaks are more than a place to dine. They represent a bigger picture of Malaysian society.

The affordable price tag and the halal food preparation establish the stalls as spaces where the melting pot of Malaysia’s multiculturalism thrives and social tensions temporarily cease, as long as patrons are willing to adhere to the Islamic restrictions of eating halal ingredients and abstaining from alcohol and pork.

Food sociologist Dr. Eric Olmedo and anthropologist Dr. Shamsul Amri Baharuddin deemed the open-air, unpretentious food establishments as the perfect space for social cohesion in 2018.

“Mamak culture and outlets have become platforms of integration and social gathering centres for different classes and ethnic groups,” Shamsul said.

“People always look relaxed, and there’s a lot of freedom. You can talk loudly about anything. There’s no censorship,” Olmedo said. “It can go from football to politics. You can see migrant workers from construction sites to the [wealthy] being dropped off in their SUVs. There’s no divide.”

For a shop to be considered a mamak, there should be a combination of two cultural markers: Indian cuisine and Islamic faith.

Although mamak food is considered local to Malaysians, many of the dishes have origins tracing back to Southern India. The most popular dish, a flat bread with a fluffy interior and crispy outer layer called roti canai, is believed to have originated in the Indian city of Chennai, formerly known as Madras.

“Mamak outlets have a humble beginning,” Shamsul said.

The name comes from the Tamil word ‘mama,’ meaning maternal uncle, but also is a term of endearment used by women to their future male spouse in Indian Muslim culture. The addition of a ‘k’ was most likely influenced by the natural speech patterns of the Malay language.

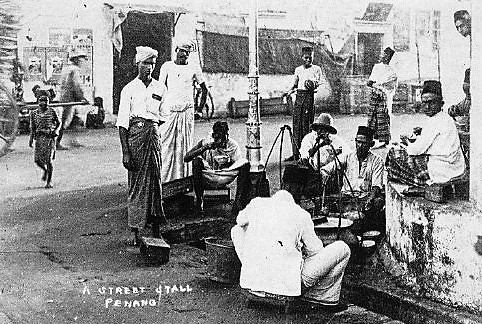

Mamaks appeared in the Malay Peninsula around the early 1900s, a time of great economic transformation when many migrants from South India arrived to work for the British as labourers.

“It provided food for [the] poor working class of Indian origins, who worked at ports and harbours, railway stations and workshops [and] public work service infrastructure projects building roads and bridges,” Shamsul said.

In the early stages of mamaks, operations were small and often run as simple, family businesses. Mamak hawkers sold their food while cycling between villages with rice and curry dishes in two baskets balanced on each end of a pole across their shoulders. Later, they upgraded to smaller stalls and eventually opened restaurants, establishing the network of mamaks predominantly run by Indian migrants.

“At the end of the day, it’s a migration story,” Olmedo said.

The Islamic Muslim identity expressed in mamaks echoes the Islamic faith and official religion of the Muslim-majority country.

Older mamaks in Kuala Lumpur city have a hardly noticeable ‘786’ numbered on their signage. The numeric value represents the Arabic phrase ‘Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim,’ the opening phrase of the Holy Quran. The phrase translates to ‘In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.’

Today, there are roughly 12,000 mamaks scattered throughout the country, illustrating that these ubiquitous restaurants are a key ingredient in Malaysian society. “There is nothing more Malaysian than a mamak,” Olmedo said.

Patrons typically have a favourite neighbourhood mamak they frequent, allowing them to build special camaraderie with the staff. Customers and servers often refer to each other by nicknames like boss or ah neh, meaning ‘big brother’ in Tamil. The trust and mutual respect often result in goodwill gestures such as small discounts or free drinks.

“Everybody respects mamak workers. They are good at their job, good customer service and they serve you food. They don’t forget your order and they will serve you fast,” Olmedo said.

To keep up with the tiring, 24-hour work cycle, the majority of mamak employees live in shared accommodations near the restaurants, allowing a quick commute.

Jemeni, 21, who migrated from India less than a year ago, is one of the eight employees at Ali Food Corner, a mamak in Malaysia’s most developed state, Selangor. “I live upstairs,” he said, pointing. “Eight of us live there, we share the room in pairs.”

Mearaen has worked in mamaks for more than two decades. Next to a station where he had made a classic mamak beverage called teh tarik, a hot tea mixed with condensed milk poured between two cups until frothy, a tray was ready to be served with large plastic mugs of sirap bandung, a rose syrup mixed with milk.

The financial situation for mamaks is expected to take a turn for the better. In February, the government reopened the job market to new foreign workers, resulting in 100,000 applications to the human resources ministry. Foreign worker applications were previously halted by Malaysia’s movement control order in March 2020.

Despite a reopened job market and a return to regular operating hours, many 24-hour mamaks remain understaffed.

“Until now [we have] problems with [a lack of] staff. That’s why I’m here working,” an employee said as he picked up a tray of iced beverages before running off toward customers.

Beyond serving quick, hot comfort meals, mamaks have long catered to football fanatics using their televisions and large projectors. Football fans would segregate themselves into different tables to create an atmosphere similar to a stadium.

Muhammad Iylia bin Arbi frequented his favourite mamak every other day, especially during the English Premier League football season before the pandemic struck.

“Mamak is not just a place to eat, to gather or relax. It’s a place to watch football,” Ilyia said, delighted to hear mamaks can resume round-the-clock operations. “Finally, I can watch football [at the mamak] again.”

Instead of pubs and waterholes, mamaks also are a preferred venue to relax and gather with friends and colleagues after a long day.

“Never once have I heard people say let’s [hang out] at Secret Recipe (a contemporary halal cafe),” Ilyia said.

On a typical day before Covid-19, a mamak would keep its lights and stove on, ready to serve at a moment’s notice.

But now as the clock approaches midnight, the chatter of the mixed crowd usually softens and more seats free up. Cars occasionally pull up to collect takeaway orders. Instead of a new crew of mamak staff preparing a fresh batch of food for the morning crowd, workers wipe down tables and stainless steel shutters are pulled down.

Everyone hopes the clanging pots and pans and football chants inside the mamaks will soon continue throughout the night.