“Don’t cry on Singles’ Day – go to Vietnam and find yourself a bride!” urged a Chinese matchmaking website last year. A free place on a group tour to Vietnam was up for grabs, tailored for men with a rather specific interest in the country – those keener to peruse the ladies than sample the pho. Many so-called ‘leftover men’ in wealthier Asian countries seek wives through brokers in comparatively poor Vietnam, but it’s more than distorted gender ratios that result in these marriages, and the brides are often left vulnerable to dependence, exploitation and abuse.

Vietnamese women made up 34% of South Korean men’s international marriages in 2011, significantly more than brides from other Southeast Asian countries (9% were Filipino, 4% were Cambodian), according to government-run Statistics Korea. The divorce rate for Vietnamese-Korean couples is more than 30%, with mother-in-law conflict, language barriers and mistreatment cited as the main reasons, according to a report by Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Brides equate marrying a foreigner with escaping the poverty cycle. “Rural girls here have no knowledge of the world and can’t imagine a worse situation than what they’re leaving behind,” said To Phuong, 30, a woman originally from the Mekong Delta, Vietnam’s poorest region.

A culture of filial piety also drives these marriages. “Children born into rural Mekong families believe they are indebted to their parents for giving them life; they’re prepared to try and tolerate whatever fate gives them, as long as it helps their family,” Phuong added.

In Al Jazeera’s recent Asian Brides for Sale documentary, Professor Jacqueline Aquino Siapno of Seoul National University said: “A Vietnamese bride in South Korea will often send enough money home to build houses and pay for the healthcare of her ageing parents – basically doing work the state is supposed to.”

Data from the World Bank shows Vietnam ranked second among Southeast Asian remittance-receiving countries, with migrants sending more than $8 billion back to the motherland in 2010 – about twice the amount generated by tourism.

Asian men prone to shopping for Vietnamese brides “are stereotyped as lower class, poor and undesirable to local women in their own country”, said Dr Young Jeong Kim, a researcher at Oxford University’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society. According to a report by Singaporean women’s rights NGO the Association of Women for Action and Research (Aware), Singaporean men seeking foreign brides tend to be over the age of 40 and some have chronic health problems. “[They] use the foreign bride trade to fill their need for personal care… the bride plays the role of an employee rather than a spouse,” said the report.

Kim cites a geographical form of hypergamy – where women are expected to marry men of a higher social status – as another cultural driver of marriage migration. This situation results in lower-class men in wealthier Asian countries struggling to date women further down the social hierarchy than themselves. They then shift their focus to women from less developed countries such as Vietnam. “Korean men use hypergamy to emphasise their superiority, which enables the victimisation of migrant women,” said Kim.

Reports of brokered brides running away, committing suicide and being murdered have piled up. Isolated from their families, often without money or legal standing, and unable to communicate with local law enforcement, they are acutely vulnerable. Chinese newspapers often report on Vietnamese women ending up in mental hospitals after fleeing their husbands. Last year Vietnamese newspaper Tuoi Tre interviewed a Vietnamese woman in Fuzhou Mental Hospital, who claimed her husband’s family would beat her because leg and arm malformations prevented her from doing heavy labour. She told the newspaper that the family drove her onto the street empty handed.

The report from Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs revealed marriage brokers sometimes withhold potential husbands’ dubious criminal and health records from would-be brides. The report highlighted a case from 2010 in which a South Korean man, known to have severe schizophrenia, stabbed his Vietnamese wife to death after eight days of marriage. The report also warned that newly arrived brides in China are at risk of being pimped out or sold on by their husbands.

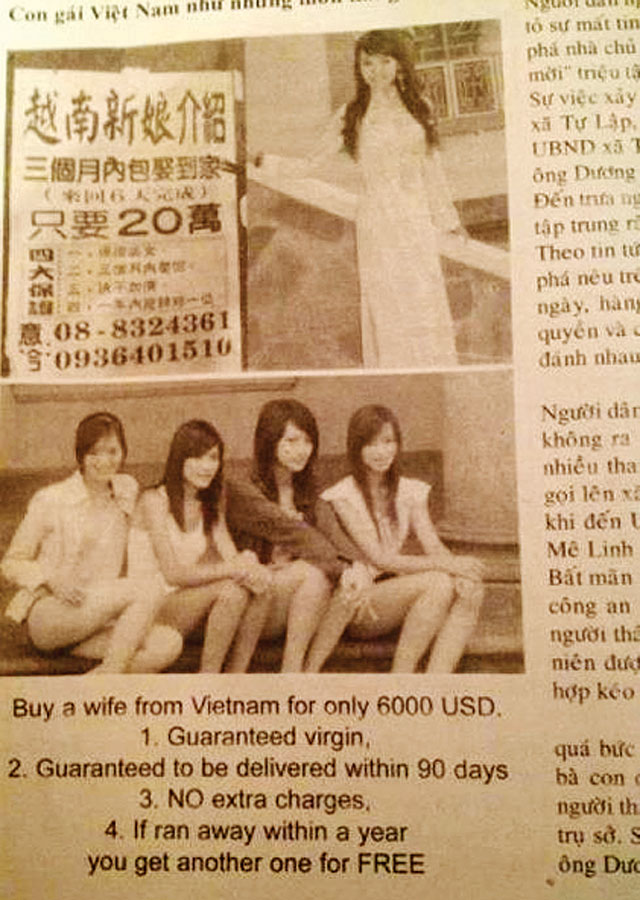

The cultural brew of hypergamy, filial piety and skewed demographics has marriage brokers lucratively helping supply meet demand. Most operate legally and according to regulations in South Korea and Singapore – a husband who is unhappy with his recently purchased bride can complain to the Consumers Association of Singapore. In China, where buying brides is illegal, brokers classify themselves as dating agencies instead. Dating website ynxn1314.com exemplifies this, condemning wife purchasing as “inappropriate” online, then adding that “more than 80% of clients find brides on our group tours to Vietnam”.

Such tours are fast paced and competitive – a quickfire wedding can follow just ten minutes of chat between visiting men and Vietnamese women. Global Times reported a case in which by the time a dithering man had settled on a girl, she’d married someone else.

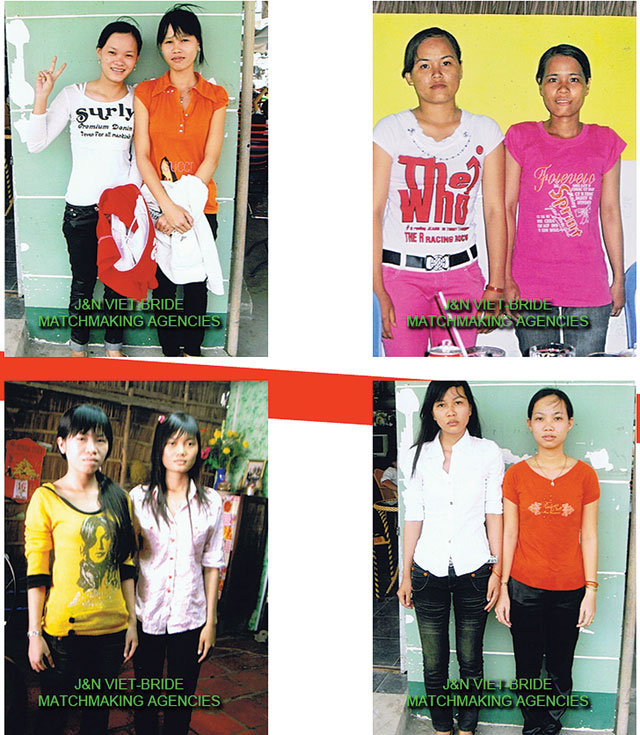

Brokers also compete with each other. Singapore’s J&N Brides’ website offers free-flow beer at wedding receptions and discounts for bulk wife purchases between friends. Life Partner Matchmaker declares itself “the only cupid in Singapore specialising in beautiful Vietnamese virgin brides for Asian men”. The latter’s prices are relatively high at SGD10,000 ($7,450) per bride – some agencies charge just SGD5,000.

J&N owner Janson Ong justifies the higher fees in a video on his website: “Most of my men are very simple-minded and don’t know how to make their wife happy, so we need a virgin. Also, in Vietnam there is a lot of HIV, so I insist the girls are 100% real virgin.” He goes on to describe cheaper agencies’ alleged techniques for faking virginity – some surgically replace a woman’s hymen, others teach wives to smear blood from a bitten finger on the bed sheets.

From the South Korean government’s point of view, the bride trade is the solution to low birth rates and an ageing society, according to Kim. The practice has been encouraged over the past two decades, but following a recent spate of suicides and murders within marriages there has been a new focus on increasing accessibility to integration classes and to shelters for at-risk women. Kim criticises integration programmes for being “assimilative to Korean culture rather than respectful of different cultures” and says racial prejudice against Vietnamese wives and their children is an obstacle in ethnically homogenous South Korea.

“A significant problem often faced by non-nationals in Singapore is that their marital status may affect their immigration status,” said Jolene Tan, senior manager of Aware. In response to this problem, the NGO established a helpline giving migrant wives legal advice about divorce.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issues regular warnings against the illegal purchase of Vietnamese wives and vows to crack down on brokers. But experts believe high demand simply leads to increased numbers of underground brokers offering fraudulent marriages and endangering brides. “It’s easier for the government to supervise and regulate, rather than crack down with force,” Liu Guofu, an immigration law expert from the Beijing Institute of Technology, told GlobalPost.

The Vietnamese police periodically bust illegal brokers. In March, six people were arrested in the Mekong Delta region for allegedly selling women into marriage with Chinese men. The practice is largely unregulated at the Vietnamese end, however, and the report by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs admits that local marriage counselling centres “are not in a position to meet the pressing demands of migrant brides for information about host countries, or to provide basic communication skills training to facilitate integration in their future home communities abroad”. The government makes an effort to repatriate women whose overseas marriages fail, but this is difficult if their original passports have been confiscated or destroyed, as is often the case.

Despite brokers’ websites being splattered with animated hearts and whimsical girls in white dresses, brokered marriages are based on ignorance and economics. As matchmaker Ong says in his video: “Bringing an 18-year-old home for SGD10,000 is cheap. You don’t need to waste money dating.”