Two years since the first cases of Covid-19 elicited concern in the medical world, buzzwords like “unprecedented” and “new normal” have lost their novelty. Folded into the cultural lexicon, these terms have become emblematic of the uncertainty of the Covid era, the challenges it presents and the shared experience of living through a pandemic.

In Cambodia, signs of pre-Covid daily life have begun to return, as schools across the country open and students, teachers and administrators settle into augmented-routines that are a welcome change from the disruption of the past two years. Now, with lockdowns and red-zones looming in the rear view and despite Omicron surging, there is opportunity for reflection on the challenges, lessons learned and lasting repercussions on the nation’s education system.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on student learning,” explained Asia Development Bank (ADB) Country Director Anthony Gill. “Even though significant efforts have been put into assuring [sic] continuous learning during the school closures, there is likely to be a large learning loss for many students, especially for the most vulnerable ones.”

ADB, a key development partner in Cambodia’s education sector since the early 2000s, has committed a $20 billion Covid-19 response package and is working with the Ministry of Education Youth and Sport (MoEYS) to address impacts of the pandemic.

According to Gill, the MoEYS Education Management Information System has published no statistical evidence of increased dropout rates — a key metric — however, he admits the country is facing a “learning crisis” that has driven students and educators to “alternative arrangements” to navigate the situation.

The need for these “alternative arrangements” was born out in a February 2021 report from international NGO Save the Children, one of few published studies looking into Covid-19 impacts on Cambodia’s primary education.

While longer-lasting consequences of months out of the classroom will likely reveal themselves over time, the study highlighted a number of key factors multiplying the challenges facing students.

Unsurprisingly, the report found a lack of access to learning materials and tools for distance learning proved to be the leading difficulties in connecting students and educators, especially in rural and remote areas.

Echoing these findings is Savy Ung, country director for Caring for Cambodia, an international education NGO operating in and around Siem Reap since 2003.

Responsible for operations at the group’s 21 partner schools, he saw the impacts of Covid-19 on his staff’s ability to reach students, although he also perceived resilience that was cause for optimism.

“The pandemic has closed schools and made the entire school system stuck: organisation, teaching, human resource management,” Savy explained. “It’s caused a lot of problems but Covid-19 has also taught us a lot. The teachers have been able to adapt to the pandemic situation at all of our schools.”

While schools across the country are on a morning/afternoon split schedule, enabling classroom social distancing that may become part of the readjusted normal, only months ago, even this “alternative arrangement” was out of the question.

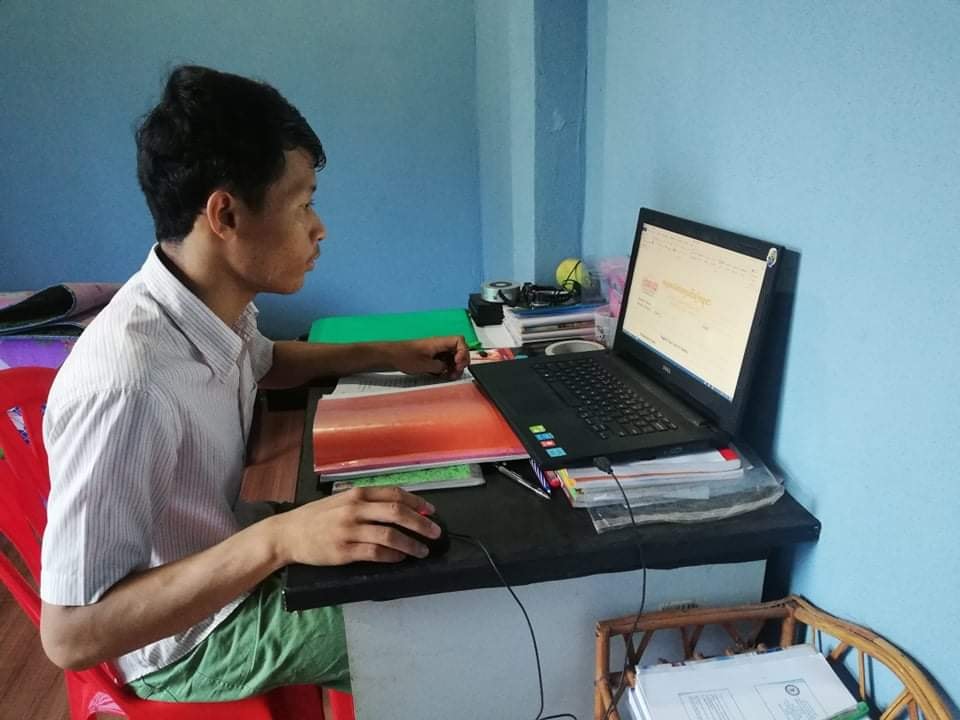

Remaining open throughout the pandemic, integral to CFC’s operations was the use of technology facilitated by teachers like Morn Sokcheng. One of the organisation’s 11 ICT teachers, the support his team provided to students and staff proved vital to the integration of technology in the school’s teaching strategy.

Even before the pandemic, weekly training sessions for CFC teachers provided many with a digital literacy foundation that better prepared them for the coming challenges. However, not all instructors were equally comfortable with the shift to distanced learning.

“Some of the teachers didn’t have as much technology skills, so they needed more help from ICT teachers,” Sokcheng explained. “We had to make sure that we were ready to provide the support that students and staff needed.”

This support came in the form of refresher exercises on Google docs, Google forms and other useful programs, as well group chats where teachers could ask for help with specific platforms and digital tools. Sokcheng and the other ICT teachers also were regularly tapped for troubleshooting when unforeseen difficulties arose during lessons.

“If the teachers, administrators or even the principal had an issue with something regarding technology, they could message us directly through a group chat,” he said. “We could give them support immediately and help them solve the problem.”

Another international NGO focused on education in Cambodia, Aide et Action, also provided tech support and training to public school teachers, administrators and students over the last two years. However, upskilling teachers on the fly in the middle of a pandemic proved a difficult task.

Project Director Marong Chhoeung cited a general lack of ICT skills among government school teachers as a leading obstacle, while also pushing teachers and students to expand their knowledge in the face of this new challenge.

“Before Covid, we never expected that our teachers would need to use ICT,” he said. “But the teachers have changed their approach to teaching; they began using ICT tools to upgrade their own capacity.”

These technologies undoubtedly mitigated the learning loss for students across the country. However, as in other less-developed countries, Cambodia’s lack of internet coverage and limited smartphone access meant low-tech solutions were necessary to supplement digital learning.

“Most of the children, they cannot access online learning well, especially in the rural areas,” Marong explained. “So we helped some target schools with their online learning, but we also supported small group learning at the community base.”

For Kimheut Cheoun, secondary assistant at CFC’s Aranh High School school in Siem Reap, closing the gaps where technology couldn’t reach meant packing up supplies, heading out to area communities and sometimes doing a bit of detective work.

“If there was a student that wasn’t present in online lessons, we would always try to find out where they were and what they were doing,” she said. “We would message their friends, call them and their parents and eventually we would go to their house to try to see the situation that was keeping them from class.”

CFC launched a mobile homework program from July to November of 2021 through which teachers like Kimhuet travelled in vans equipped with wifi hotspots to provide learning materials and mobile data cards, assign homework and hold socially distanced lessons. Often taking place at local pagodas serving as ad-hoc community centres, teachers would chart progress and maintain contact and relationships with students.

“It helped create a stronger connection between the teachers and the students and it helped build trust between the parents and the teachers,” she said.

Visiting 10 communities and reaching 430 students daily, some CFC teachers had to travel 70 kilometres (43 miles) to meet students forced to migrate as their parents searched for work during the pandemic. While learning has undoubtedly suffered during Covid-19, Kimhuet believes this commitment will have a lasting effect on students’ lives.

“If the teachers don’t care about their students, they are more likely to drop out,” she explained.

With schools open, the focus of educators has shifted to getting students back into classrooms and analysing the impacts of the learning loss they have experienced. Marong and his team are providing guidance and training to the Cambodian government’s District Training Monitoring Teams (DTMT). Charged with screening students who have fallen behind, the groups interview and assess slow learners and provide them with additional support during the first three months of the school year.

Similarly, the Academic Support programme at Caring for Cambodia was reorganised to use a testing process to identify students who fell behind. Slow learners and students identified as being at risk of dropping out are monitored and provided with special attention and assistance to help them catch up and return to their appropriate grade level.

Savy credits the return of nearly 100% of CFC students to his teachers’ commitment during the pandemic and the personal attention students receive in the Academic Support programme. Though the work towards recovery is just getting started and CFC is still struggling with how to keep technology in the hands of staff, Savy, Kimhuet and many others in the sector feel teachers are better equipped to deal with whatever uncertainty the future might bring.

“We learned a lot of lessons. About technology, lesson management and problem solving,” Kimhuet said. “Due to this Covid-19 situation, the students are stronger, the teachers are more experienced and have more skills. If a pandemic were to happen again, we would be ready.”

This article has been written in partnership with Caring for Cambodia, as a part of an ongoing series exploring education in Cambodia and the steps being made to bring hope to future generations. Find out more here.