A Kingdom of sand

Much of Cambodia's rapid economic growth in recent decades can be attributed to one substance: sand. Homes are built with it, islands created and wetlands filled. But while it's being extracted en masse from the Kingdom's rivers, environmental considerations in the shadowy industry are hard to come by

Borin Sopheavuthtey contributed reporting to this article. Photos by Enric Catala

Each morning, a flotilla of barges steam up the Mekong River from Phnom Penh.

They’re riding low in the water by the time they return, weighed down with coarse sand that might form a new section of the capital, rising in fits and starts on the river bank. Not far from the bonanza of Phnom Penh’s Koh Pich area – itself a massive infill on what was once a small, natural island – a crane floating on a barge plunges the jaws of its great metal bucket into the water and hauls up great dripping piles of sand to fill another flat, grey barge.

Sand is reshaping Cambodia, pouring into landfilled wetlands and stirred into the concrete that raises a new skyline in Phnom Penh and in other cities across the Kingdom. According to data provided to the Globe by the Ministry of Mining and Energy, in 2019 about 9 million cubic metres of sand was dredged up, hauled off and used mostly to feed a construction industry worth nearly $10 billion last year alone.

The official volume of Cambodian sand mined in 2019 could form a cube with edges of a little more than 208 metres. That’s roughly the height of the under-construction Gold Tower 42 project, which will be one of Cambodia’s tallest buildings when finished.

But researchers say accurate regional data on Mekong sand mining can be sparse, thanks largely to unregulated industries scrambling for the hot commodity. As the environmental toll of dredging has risen in profile, those like Marc Goichot, freshwater chief for the Asia Pacific office of the World Wildlife Fund, say efforts to study further have run aground. Though sand is generally understood to be the most-mined substance in the world, anyone who provides estimates of scale hedge their guesses with terms like “conservative”.

“More sand is extracted than any biomass or any other thing,” Goichot said. “I guess only water would be bigger in terms of volume, but it’s [sand] completely undercover and opaque so it’s very difficult to get any info.”

Goichot believes the true scale of Mekong sand extraction in Cambodia could be anywhere between three to five times the official record. He thinks that kind of high-bar margin of error could probably be found elsewhere along the river where demand is high.

“It is amazing we can offer such little information given that sand mining is by volume the largest extractive industry in the world,” said Goichot.

Even if official numbers are entirely accurate, a study published January in the science journal Nature Sustainability suggests the amount dredged is still twice as much as what the river can naturally replenish on its own after years of sediment trapping by upstream hydroelectric dams.

As silty Mekong riverbeds fall, they change the course of the river itself. Erosion is a natural process on the river’s edge, but hydrologists say the widespread mining of sand has created an increasingly erratic flow pattern that lends itself to bank collapses in Cambodia and downriver in Vietnam. Researchers there believe a large black-market industry is speeding up saltwater intrusion and loss of land to the sea in the country’s fertile delta.

In 2013, Goichot and hydrologists Jean-Paul Bravard and Stephane Gaillot published a study that estimated almost 34.5 million cubic metres of sand were extracted in 2011 between Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam. Based on surveys conducted between 118 extraction sites in the studied countries, the researchers believed Cambodian river dredgers had pulled 18 million cubic metres of sand, making it the regional leader for sand extraction in that year.

The 2013 study hasn’t been replicated in the long years since, but is still used as a benchmark by other river researchers, who cite the findings as one of the best-educated guesses available in a murky industry.

Our method was based on declarations from extractors. At the time, they were more inclined to respond accurately. Now that the socio-ecological impacts are better understood, they may not wish to respond

Today, Goichot believes the survey was “very much an underestimation” of the industry at the time. For now, he doesn’t have a followup planned.

“Our method was based on declarations from extractors,” he said in a message. “At the time, they were more inclined to respond accurately. Now that the socio-ecological impacts are better understood, if asked again today they may not wish to respond, or provide less reliable responses.”

But even if data isn’t always easy to come by, it does exist in some form in the ministerial offices of Phnom Penh.

“We do have a proper record of the amount of sand we dredge,” said Yos Mony Rath, director general of mineral resources at the Ministry of Mines. “Based on the figures reported, we can say that the number has been increasing.”

Last year, Rath’s office oversaw licenses extended to companies that together accounted for the approximately 9 million cubic metres of sand extraction. In 2018, Rath said the ministry had licensing out for 8 million cubic metres, an official doubling in the haul of sand from the year prior, when the ministry had licenses for about 4 million cubic metres of sand.

Dredging is an old practice, and besides the economic value of sand, there is a real need to keep waterways navigable for boat traffic. Rath pointed to river maintenance as a key objective for dredging in Cambodia, asserting that dredging operations have become more important as water levels fall in the Mekong and its tributaries.

He also said the Ministry is conscious of bank collapse hazards and works with local communities to mitigate risk. The Ministry keeps a hotline for the public to report illegal or improper dredging activity. Rath told international media in February that the hotline has never received a complaint.

That might be the case, and though Rath told the Globe his Ministry works with other government bodies to safely oversee sand mining, local media still regularly feature stories from residents fearful that dredging will cause their homes to collapse into the river.

“Whenever, there is a sand dredging operation happening in a certain area, we would invite the villagers there to join our public discussion,” Rath said. “Some would say they are afraid of bank collapse. Here, it is our responsibility to tell them that we are not going to dredge sand from the area where a bank collapse happened.”

Though his office handles permits for dredgers, Rath said they make siting decisions based on hydrology studies from the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology – a description Chan Youttha, spokesperson for the latter ministry, didn’t confirm when contacted by the Globe, saying in a brief message that his ministry didn’t have anything to do with sand dredging.

The Ministry of Environment also officially plays a hand in the bureaucracy of sand, as dredgers are required to submit to them environmental impact assessments based on the size and scope of proposed operations. When asked about this, Ministry spokesman Neth Pheaktra deferred all questions back to the Ministry of Mines.

In a meeting there, Rath spoke more openly, adding at one point that he would’ve rejected a similar interview request from researchers. He didn’t deny the link between sand dredging and bank collapse, but described the industry as just one link in natural erosion.

“The findings of [our hydrology] studies are not confidential or anything, but there is no reason to publicise it,” Rath said.

He didn’t respond to follow-up questions sent afterward about measures to prevent illegal or unregulated sand dredging.

Even if not officially withheld, little is typically publicised about sand mining despite its scale. The industry has grown quietly despite controversies that have, in the past, prompted sporadic government commitments to tighter regulation.

The massive amount of unaccounted-for sand, corroborated by Singaporean imports data, sparked allegations of fraud that found little in the way of official rebuttal

In 2011, sand dredging carried out mostly by the tycoon Ly Yong Phat in coastal Koh Kong province first drove the industry into major scrutiny. Local villagers there decried ecological damage and dwindling fish populations caused by intensive mining.

Later in 2015, after some bureaucratic shuffling over responsibility for river sand mining, Prime Minister Hun Sen pushed the industry more fully under the oversight of the Ministry of Mines and Energy. That same year, a growing public unease with sand mining pushed the mines ministry to announce a stricter licensing process for would-be dredgers, including a ramped up focus on environmental impact assessment.

Amidst all that, the ministry held a public auction for sand dredging that awarded only four permits. Not long after, the ministry switched tracks and ramped up permitting, granting licenses to almost 70 firms by mid-2016, less than a year after the auction.

Public scrutiny leaped when data from the United Nations’ Comtrade office revealed a $700 million discrepancy in Cambodia’s official export tally to sand-hungry Singapore. The massive amount of unaccounted-for sand, corroborated by Singaporean imports data, sparked allegations of fraud that found little in the way of official rebuttal.

Amidst the furor, in 2017, the Kingdom officially banned exports of sand. But that hasn’t stopped the dredging and, since then, the industry has turned inward, pumping up sediment first to fill lakes and wetlands for development, and then to build towers and sprawling developments – much of which is happening in and around Phnom Penh.

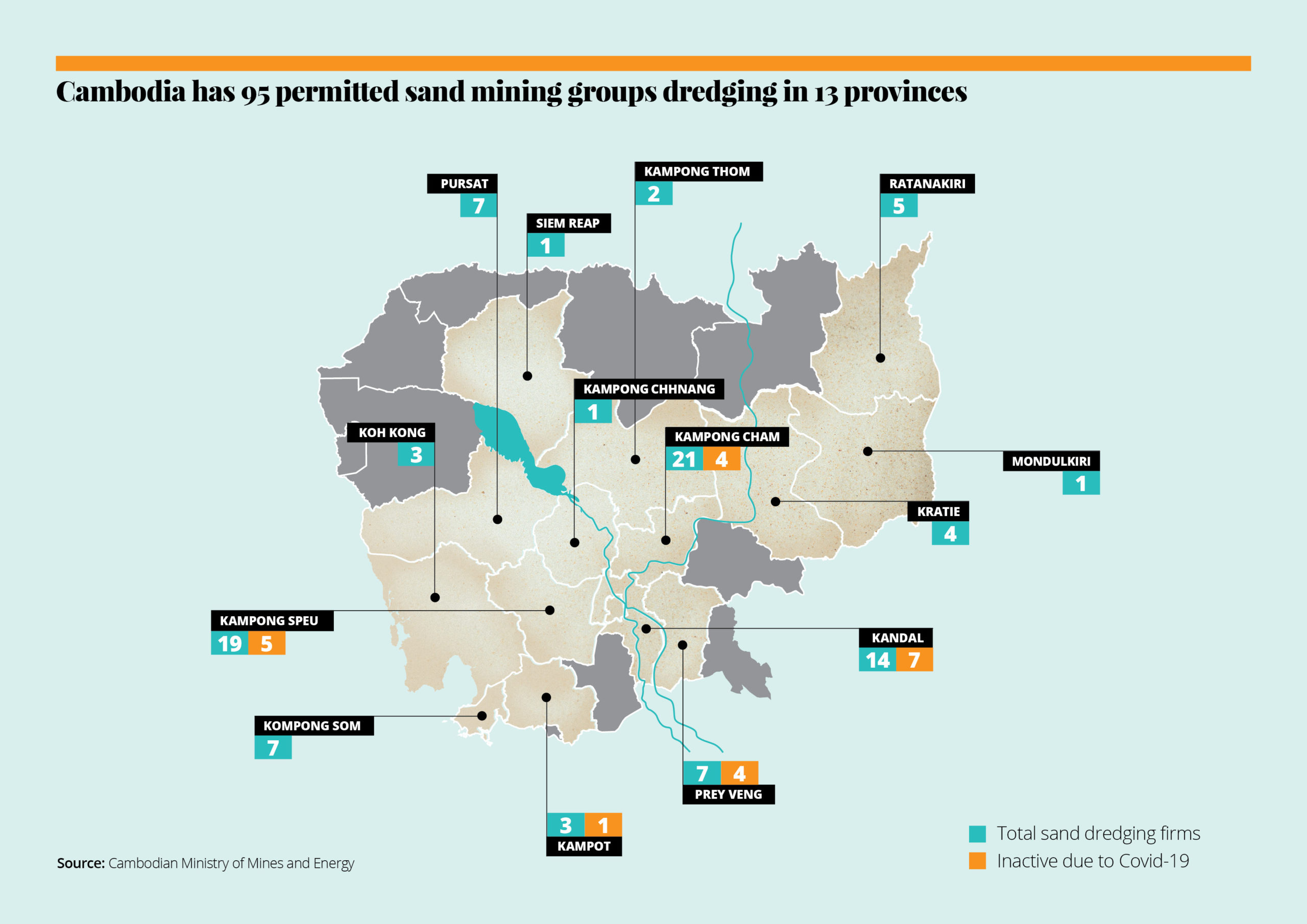

Today, there are 95 firms officially permitted to mine sand around the Kingdom, though 12 have gone inactive as a trickle-down effect of the Covid-19 pandemic. The names of dredging groups have never been widely publicised, but Rath provided the Globe with what his office said was a full list of groups licensed to mine sand in Cambodia.

On the long stretch of river that runs through Phnom Penh, between Kratie province in the north and the Vietnamese border to the south, there are 46 companies licensed to mine sand. By volume, the largest of these is the Jin Ling Construction Company, which Rath said has been approved this year to extract as much as 3 million cubic metres of sand from 147.7 hectares of the river around the border of Kandal and Kampong Cham provinces.

Closer to Phnom Penh, Rath said, dredgers are pumping sand to fill in areas for new developments. These miners include Hero King, a firm owned by the son of timber tycoon Try Pheap and identified in national media as providing sand to fill in the city’s southern Cheung Ek wetlands, and another dredger known as the Kun Sear Company.

Sand in the Mekong is a renewable resource of sorts, given enough time and a healthy natural system. But all major available studies of sand in the river system suggests this system has all but broken down thanks to a combination of mining and damming.

Chris Hackney is a research fellow at Newcastle University who’s built a speciality in sand. It was his team that, at the beginning of this year, published the study in Nature highlighting the link between unsustainable levels of sand mining and widespread river bank instability and in the lower Mekong.

The group had originally been monitoring sediment transport more generally in the river, but Hackney said his team was quickly struck by the level of visible sand activity.

“Sand mining wasn’t something we particularly considered when we started [the study], it was still fairly under the radar,” he said. “But then you go down to the riverside in Phnom Penh and see that just about every other boat is full of sand up off the riverbed.”

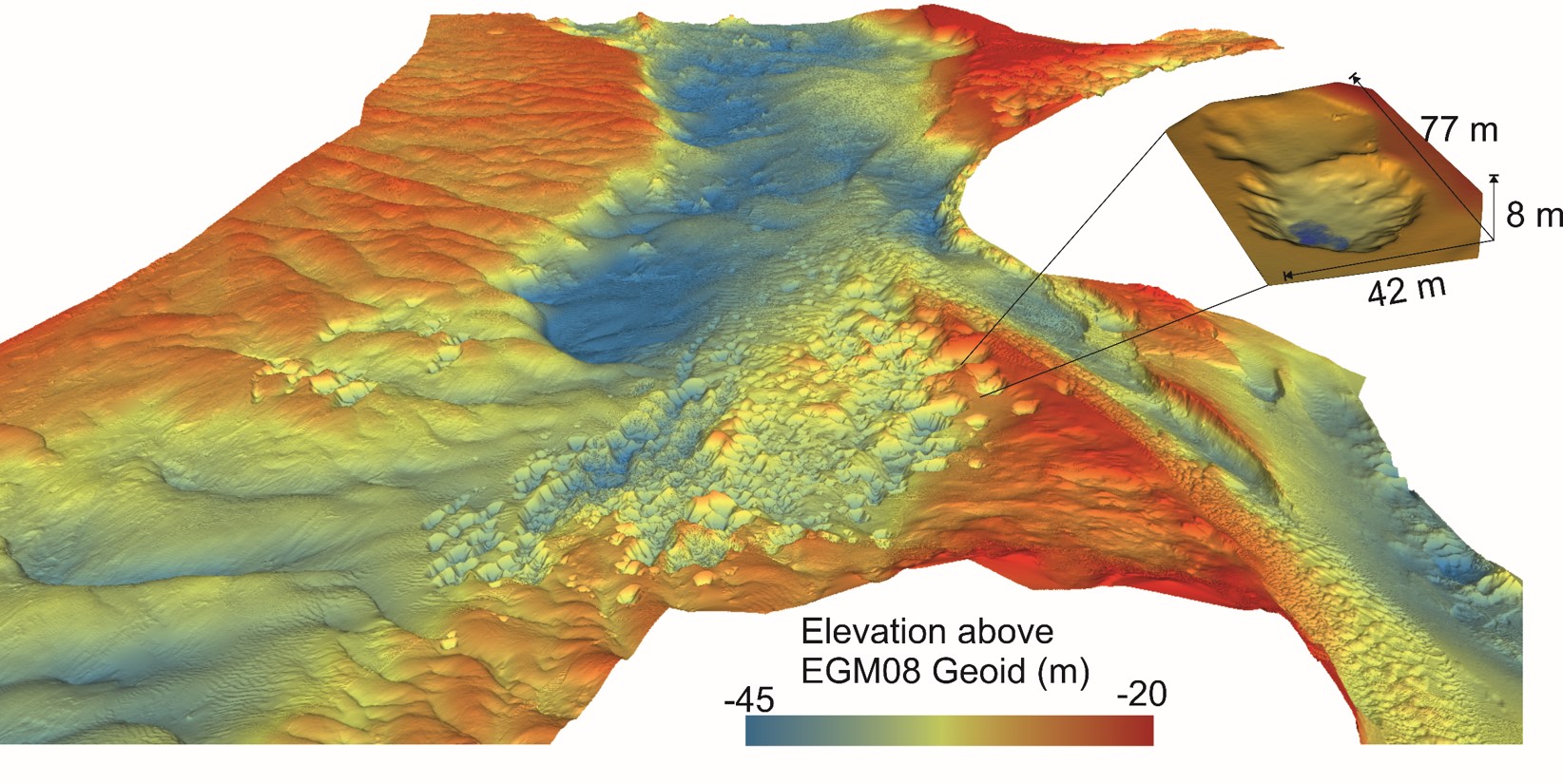

What followed from the team, which included researchers from three universities and the Cambodian government, was a comprehensive mapping of the bed from the capital to Kratie using high-definition sonar that captured images every 12-18 hours.

“You can see the sand dunes move through your [time] window and that rate gives you an indication of how much sand the river is transporting naturally,” Hackney explained.

The sonar images in the now-published study may provide the best overall sketch of an underwater landscape pitted and pockmarked by the effects of dredging. In some hotspots, such as around the Phnom Penh junction of the rivers Mekong, Bassac and Sap, the riverbed has been lowered by as much as eight metres – more than enough to cause widespread seasonal instability on the banks, according to the research team.

Such a trait fits in a wider narrative of the Mekong that has become a litany of red flags, from sterile blue waters to the increasingly weak and unpredictable reversal of Cambodia’s great Tonle Sap. As sand mining and other factors, including global climate change, push the mighty river’s natural systems into a new state, Hackney said events like major bank collapses could be part of a new normal.

“It’s hard to unpack the natural and human influences in this, but it’s clear that there will be some impact. It’s just figuring out the scale at which that’s going to manifest itself,” Hackney said of sand mining. “Society needs sand, there’s no way around that, but it’s got to be done in a way that won’t hurt everything else.”